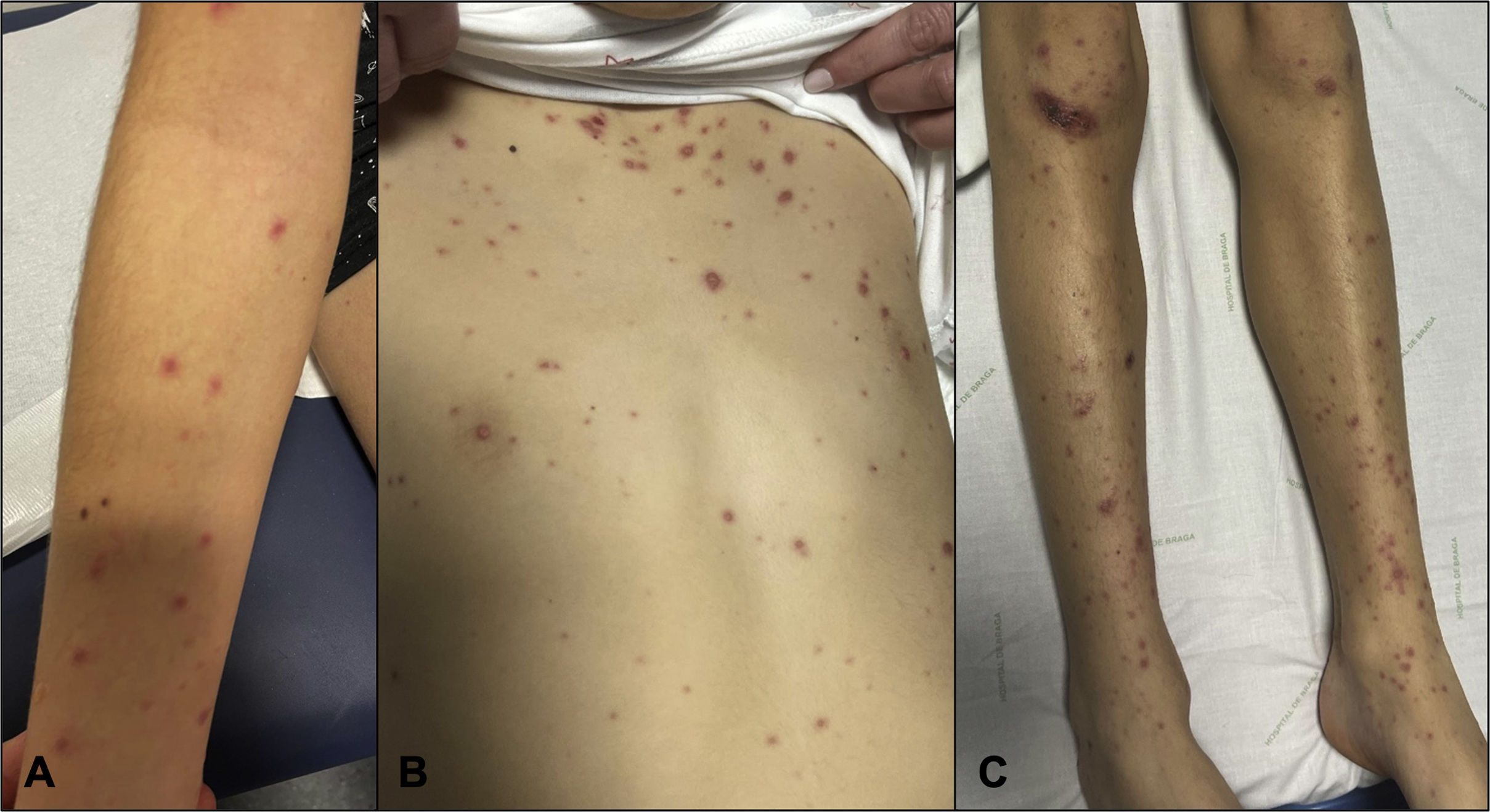

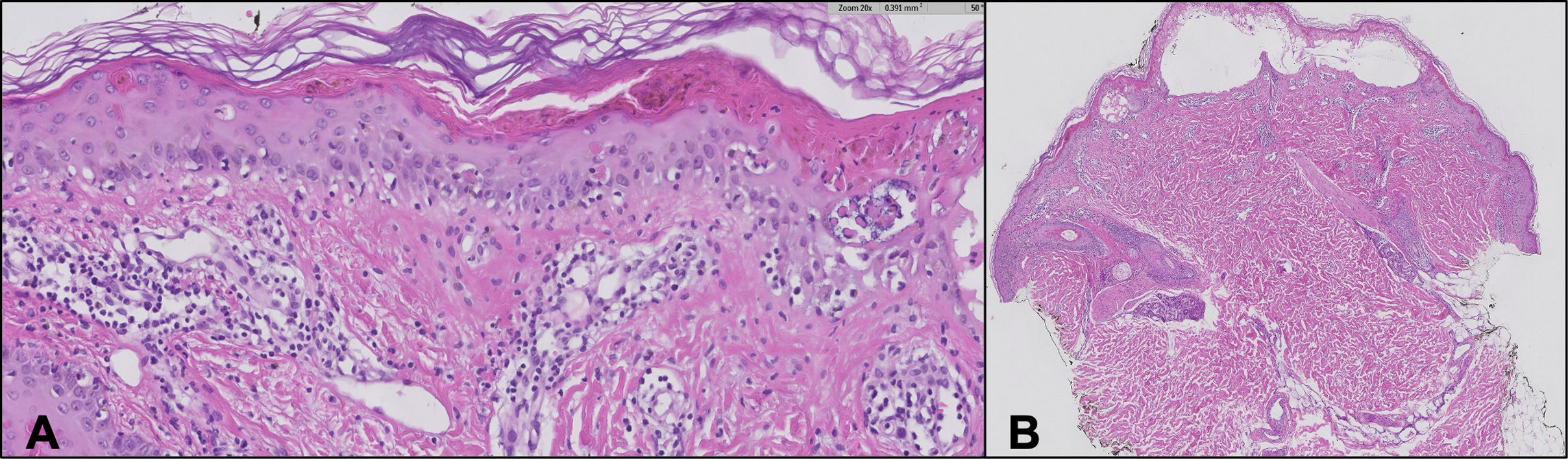

A male adolescent aged 14 years presented with fever, conjunctivitis, sore throat, oral ulcers, swollen lips and rash with onset 5 days prior. On day 2, a throat swab tested positive for group A Streptococcus, and amoxicillin and ibuprofen were prescribed. On day 5, the rash worsened (Fig. 1) with extensive mucosal involvement (Fig. 2). There was no history of recent infection or drug intake compatible with the symptoms. At this point, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or erythema multiforme major (EMM) were suspected. The treatment included intravenous immunoglobulin (1 g/kg/day) for 4 days and methylprednisolone for 5 days, which achieved progressive improvement. The findings of the skin biopsy supported the diagnosis of SJS (Fig. 3).

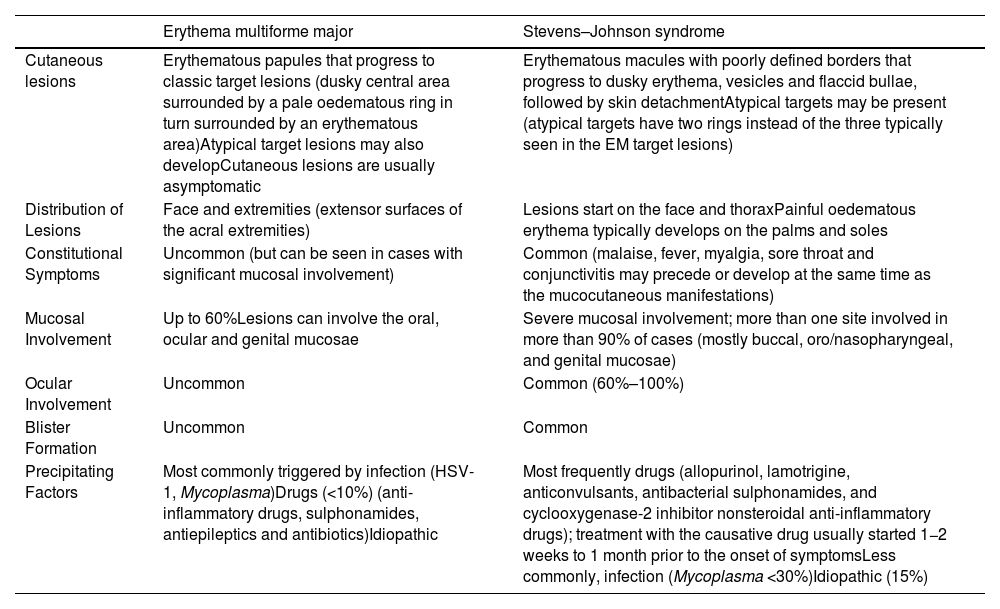

In this case, the streptococcal infection and administration of amoxicillin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs could have triggered the condition, or the patient may have presented with SJS/EMM at the outset. Distinguishing between EMM and SJS is challenging (Table 1). Both are characterized by widespread rash and mucous membrane involvement. However, EMM usually presents with typical target lesions mainly involving the skin, while SJS manifests with widespread erythematous macules and blisters, often leading to severe skin and mucous membrane detachment, with a higher risk of complications.1–3 In addition, in the case of SJS, two or more mucosal surfaces are usually involve and the patients tend to experience systemic symptoms preceding the cutaneous manifestations.2 Understanding these nuances is essential for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention.

Comparison of the clinical features of erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

| Erythema multiforme major | Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous lesions | Erythematous papules that progress to classic target lesions (dusky central area surrounded by a pale oedematous ring in turn surrounded by an erythematous area)Atypical target lesions may also developCutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic | Erythematous macules with poorly defined borders that progress to dusky erythema, vesicles and flaccid bullae, followed by skin detachmentAtypical targets may be present (atypical targets have two rings instead of the three typically seen in the EM target lesions) |

| Distribution of Lesions | Face and extremities (extensor surfaces of the acral extremities) | Lesions start on the face and thoraxPainful oedematous erythema typically develops on the palms and soles |

| Constitutional Symptoms | Uncommon (but can be seen in cases with significant mucosal involvement) | Common (malaise, fever, myalgia, sore throat and conjunctivitis may precede or develop at the same time as the mucocutaneous manifestations) |

| Mucosal Involvement | Up to 60%Lesions can involve the oral, ocular and genital mucosae | Severe mucosal involvement; more than one site involved in more than 90% of cases (mostly buccal, oro/nasopharyngeal, and genital mucosae) |

| Ocular Involvement | Uncommon | Common (60%–100%) |

| Blister Formation | Uncommon | Common |

| Precipitating Factors | Most commonly triggered by infection (HSV-1, Mycoplasma)Drugs (<10%) (anti-inflammatory drugs, sulphonamides, antiepileptics and antibiotics)Idiopathic | Most frequently drugs (allopurinol, lamotrigine, anticonvulsants, antibacterial sulphonamides, and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs); treatment with the causative drug usually started 1−2 weeks to 1 month prior to the onset of symptomsLess commonly, infection (Mycoplasma <30%)Idiopathic (15%) |