Parenteral antibiotic treatment has been classically developed in hospitals and is considered as a hospital procedure. The development of Hospital at Home Units (HHU) has led to an increase in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) in paediatric patients. The objective of this study is to describe our experience, as an HHU integrated within a Paediatric Department, in home antimicrobial therapy over a period of 12 years.

Patients and methodsThis prospective and descriptive study included every patient with a disease requiring parenteral antimicrobial therapy who was admitted to our HHU from January 2000 to December 2012.

ResultsDuring the study there were 163 cases on OPAT. The mean age of the patients was 11.1 years, and the sample group was comprised of 33 males and 22 females. The main sources of the treated infections were respiratory tract (76%), catheter-related bloodstream (9.2%), and urinary tract infections (5.5%). Amikacin was the most widely used antibiotic. Almost all treatments (96.6%) were via an intravenous route. Catheter-associated complications were more common than drug-associated complications. Successful at-home treatment was observed in 90.2% of cases.

ConclusionsOPAT is a good and safe alternative in many paediatric diseases.

Clásicamente la administración de tratamientos intravenosos se ha asociado a la necesidad de ingreso hospitalario. A partir de la formación de unidades de hospitalización a domicilio (UHD) se han extendido e incrementado el número de tratamientos antimicrobianos administrados por vía parenteral en pacientes pediátricos en su domicilio. El objetivo de este artículo es exponer la experiencia en tratamientos parenterales en domicilio en una UHD pediátrica durante un periodo de 12 años.

Pacientes y métodoSe realiza un estudio descriptivo, prospectivo. Se incluyeron en el estudio a todos los pacientes atendidos en nuestra UHD por enfermedad subsidiaria de tratamiento parenteral desde enero de 2000 hasta diciembre de 2012.

ResultadosSe han instaurado 163 tratamientos parenterales en domicilio. La edad media fue de 11,1 años. Por sexos, 40% mujeres y 60% varones. Las infecciones tratadas han sido, en su mayoría, sobreinfecciones respiratorias (76%), infecciones del catéter central (9,2%) e infecciones del tracto urinario (5,5%). El antibiótico más utilizado ha sido la amikacina. El 96,9% de los tratamientos fue intravenoso. La complicación más frecuente ha sido la extravasación o pérdida de vía (7,4%). Se completó el tratamiento en domicilio en un 90,2% de los casos.

ConclusionesLa administración de tratamientos parenterales en domicilio es una opción asistencial buena y segura en pacientes pediátricos.

Traditionally it has been thought that the administration of intravenous treatment required inpatient care; this situation started to change in 1974, when Rucker and Harrison1 presented their clinical experience with outpatient antibiotic treatment in children with cystic fibrosis. Since then, various publications2,3 have shown that this is a safe and efficacious modality that benefits both the patient and the family members, and that it has a good cost–benefit relationship.4

We define outpatient parenteral antimicrobial treatment (OPAT) as antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral treatment delivered parenterally to patients who are not hospitalised, that is, who do not spend the night at the hospital, and consisting of at least 2 doses given on different days.5 The administration can be intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous. The latter, while used infrequently, has been described in adult patients receiving palliative care, and requires putting in a request for compassionate use of the selected drug with the Agencia Española de Medicamentos (Spanish Medicines Agency). The term most frequently used to refer to this internationally is the acronym OPAT, which reflects the ambulatory approach to health care delivery of the United States model. In Spain we find the term “home intravenous antimicrobial therapy” (HIVAT) more suitable to refer to the integral at-home treatment of infectious disease in the patient.

There are several models for outpatient treatment administration that adhere to published guidelines for adults.6,7 The setting where the treatment is provided can be the home, day hospitals, freestanding infusion centres, emergency care and observation units, outpatient services, residential facilities and even the work place; and the treatment can be administered by health professionals or self-administered, that is, delivered by the patient or the carers.

There are few publications on this subject in Spain, especially in the paediatric field, and the main purpose of this article is to present our experience as a hospital at home unit (HHU), which is part of the paediatrics department, in parenteral antimicrobial treatment administered at home to paediatric patients with chronic underlying diseases, over the span of 12 years, and to assess its efficacy and safety.

Patients and methodsStudy designWe have conducted a prospective descriptive analysis, obtaining data from all patients served at a paediatric HHU who received parenteral treatment at home.

Team in chargeOur HHU team consists of 2 paediatricians and 2 specialised nurses who work in collaboration with social workers and primary care.

The unit provides 7h of physician coverage and 12h of nursing coverage on weekdays. Patients are seen in the emergency department of our hospital at all other times.

Sources of patient referralsOur purpose as a HHU is to avoid or shorten hospital stays, so our patients are selected from the inpatient paediatric floor or from outpatient services.

The physician in charge makes a referral to our unit, including a clinical summary and information on the antimicrobial treatment the patient is receiving and its planned duration.

PatientsTo propose this type of treatment, the paediatrician has to determine that the patient has an infectious disease requiring parenteral treatment and that hospitalisation is not needed to control the infection.

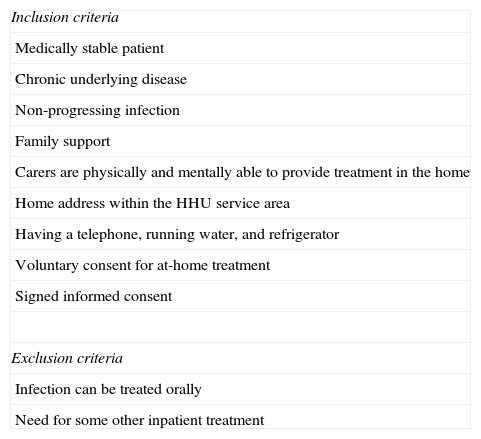

Patients were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed in Table 1.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Medically stable patient |

| Chronic underlying disease |

| Non-progressing infection |

| Family support |

| Carers are physically and mentally able to provide treatment in the home |

| Home address within the HHU service area |

| Having a telephone, running water, and refrigerator |

| Voluntary consent for at-home treatment |

| Signed informed consent |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Infection can be treated orally |

| Need for some other inpatient treatment |

The physical and mental condition of the carers was assessed by means of an interview with the HHU team.

Patient and carer trainingHHU nurses carry out the training. Its duration must be such that the patient and the carer feel confident and fully familiarised with the technique.

Should the patient need protracted treatment, as was the case of most patients included in the study, the patient and carer are taught how to self-administer the corresponding medication and how to evaluate potential complications. The patient stays in the hospital during the training period. After proper training in technique, ensuring that the patient or carer can perform it correctly, and the administration of at least one initial intravenous dose at the hospital to watch for potential anaphylactic reactions, the patient is discharged to the home to continue treatment.

In case of shorter treatments, the HHU nursing staff will perform home visits to administer the treatment, so the patient and carers are only trained in how to assess for complications.

Study variablesWe gathered data on the following variables for each patient included in the study: age, sex, hospital area from which patient was referred (outpatient or inpatient services), underlying disease, condition requiring parenteral treatment, length of training, type of vascular access, isolated pathogen, administered antimicrobial, duration of treatment, secondary adverse effects, complications during the process, and hospital readmission.

Antibiotic choice, dosage, and infusion systemThe HHU paediatricians and the medical specialist in charge decide on the most appropriate treatment for the referred patient. As much as possible, the team selects drugs with longer half-lives, lower toxicity, and requiring less manipulation by the patient.

MonitoringOnce the patient is home and while treatment is ongoing, the team talks on the phone with the carers daily and, if needed, arranges home visits by a nurse or by a nurse and a paediatrician.

Data analysisWe retrieved the data from a prospective database and did a descriptive statistical analysis. We analysed all the data with the Microsoft Excel application (for Mac): 2011.

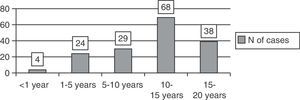

ResultsA total of 55 patients (60% male) were included in the period under study. Of all patients, 35 (63.6%) had more than one episode, adding up to a total of 163 episodes of home parenteral treatment.

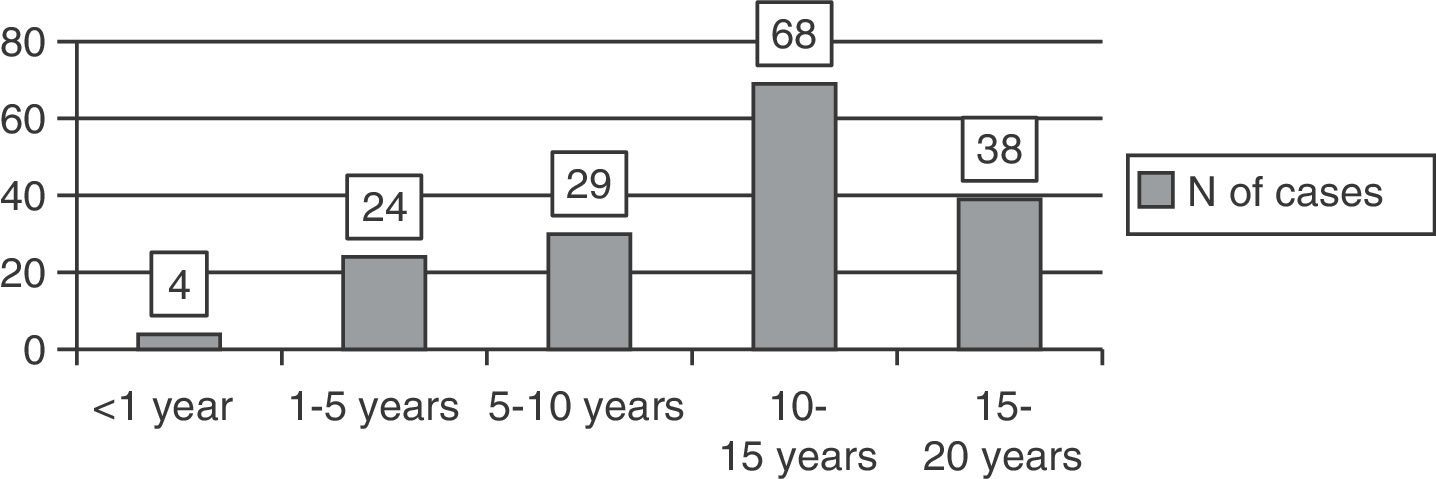

The mean age of our patients for each episode was 11.1 years (SD 4.85, range 4 months to 19 years) (Fig. 1).

In 126 episodes (77.3%), patients were referred from hospital outpatient services, especially from pulmonology (97% of patients referred from outpatient). For the remaining 37 episodes (22.7%), the patients were referred from inpatient wards, most of them from oncology (66% of patients referred from inpatient). The patients that could benefit most from this type of care are found in these settings: patients with chronic diseases that are going to need extended treatment.

The mean length of patient and carer training was 218min per episode.

Of all patients, 27 (49%) had cystic fibrosis (CF), 22 (40%) some type of cancer, 3 (5.6%) gastrointestinal diseases, 1 (1.8%) HIV infection, 1 (1.8%) bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and 1 (1.8%) had hyper IgM syndrome.

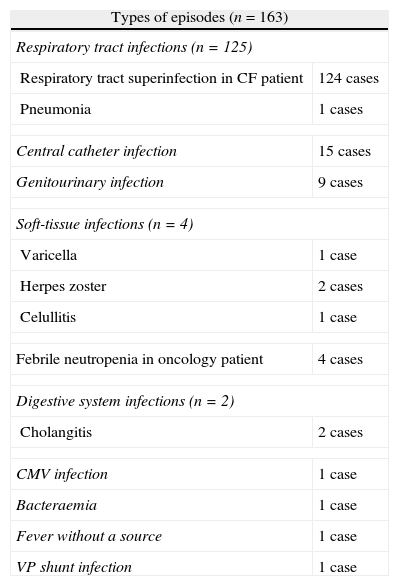

The episodes listed in Table 2 were treated at the patient's home.

Types of episodes treated at home.

| Types of episodes (n=163) | |

| Respiratory tract infections (n=125) | |

| Respiratory tract superinfection in CF patient | 124 cases |

| Pneumonia | 1 cases |

| Central catheter infection | 15 cases |

| Genitourinary infection | 9 cases |

| Soft-tissue infections (n=4) | |

| Varicella | 1 case |

| Herpes zoster | 2 cases |

| Celullitis | 1 case |

| Febrile neutropenia in oncology patient | 4 cases |

| Digestive system infections (n=2) | |

| Cholangitis | 2 cases |

| CMV infection | 1 case |

| Bacteraemia | 1 case |

| Fever without a source | 1 case |

| VP shunt infection | 1 case |

CMV: cytomegalovirus; CF: cystic fibrosis; VP shunt: ventriculo-peritoneal shunt.

The most frequently used type of vascular access was peripheral access (94.5%); central access was only used in 4 (2.5%) patients who were chronically ill and already had this device. Treatment was delivered intramuscularly in 5 (3%) episodes.

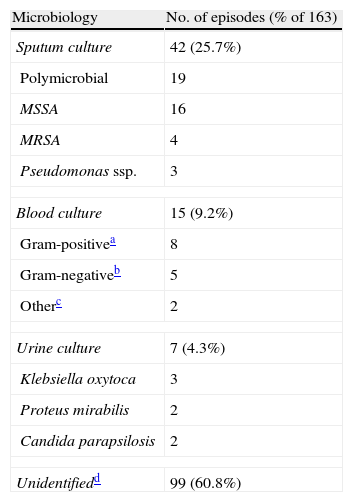

The causative agent was identified in 64 (39.2%) episodes (Table 3). The pathogen was not isolated in the remaining cases, in 4 because the culture was negative and in 95 because no culture was done.

Microbiology results of the 163 episodes of home parenteral treatment.

| Microbiology | No. of episodes (% of 163) |

| Sputum culture | 42 (25.7%) |

| Polymicrobial | 19 |

| MSSA | 16 |

| MRSA | 4 |

| Pseudomonas ssp. | 3 |

| Blood culture | 15 (9.2%) |

| Gram-positivea | 8 |

| Gram-negativeb | 5 |

| Otherc | 2 |

| Urine culture | 7 (4.3%) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 3 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 2 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 2 |

| Unidentifiedd | 99 (60.8%) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

The most frequently administered antibiotics were amikacin (n=43), ceftazidime (n=41), cefepime (n=40), teicoplanin (n=26), cefotaxime (n=12), tobramycin (n=20), ceftriaxone (n=5) and vancomycin (n=4). A combination of 2 or more antimicrobials was used in 105 episodes (63.2%), and the most common combination was ceftazidime with amikacin.

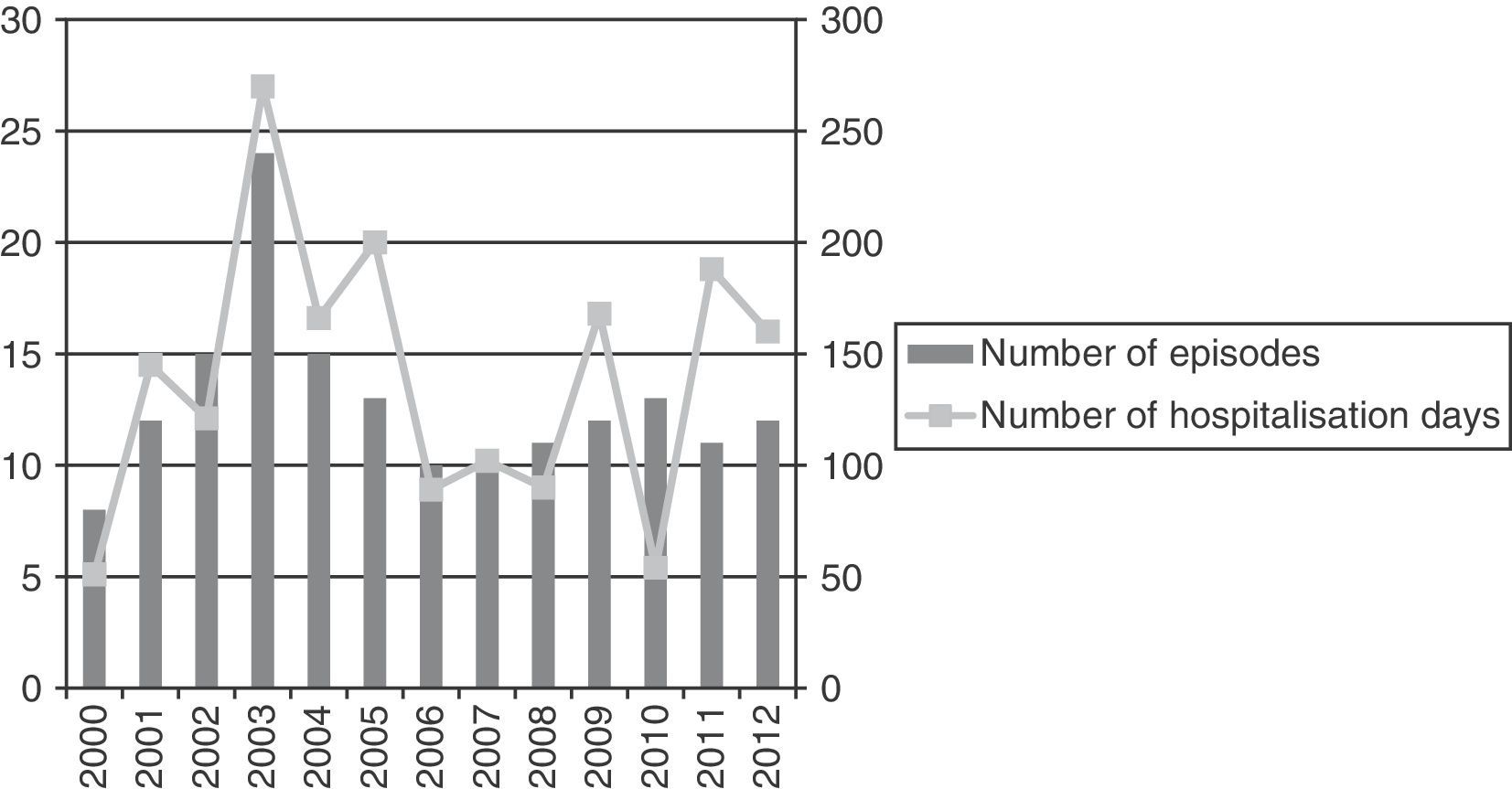

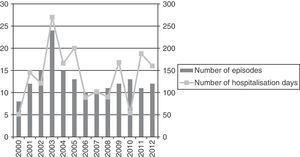

The mean duration of home treatment in the included patients was of 11.05 days (SD 5.82, range 1–25 days), and the cumulative number of treatment days was 1972 (Fig. 2). We did an estimated cost-analysis based on the costs of public health services in centres overseen by the Servicio Andaluz de Salud (Health Service of Andalusia), and found that the inclusion of patients in this programme could have saved up to 95% of the cost of conventional inpatient treatment.

The documented complications that arose during treatment were extravasation or accidental displacement of the peripheral line in 12 (7.2%) episodes, development of phlebitis in 5 (3%), exanthema or urticaria concurrent with drug administration in 5 (3%), poor technique in antimicrobial administration due to incorrect flushing of the device in 1 (0.6%), and breakdown of the infusion pump in 1 (0.6%) episode.

While the patients received care from our unit, 16 (9.8%) episodes required admission to the hospital, 4 (2.5%) of them due to poor evolution of the infectious process despite treatment, and 12 (7.4%) due to an exacerbation of the underlying disease.

Treatment was completed in the home in 147 episodes (90.2%), after which patients were discharged from our unit because of their favourable clinical outcome.

No deaths occurred during home treatment.

DiscussionOPAT is a proven efficacious and safe alternative to conventional hospitalisation of patients with bacterial infections.8,9 In our setting, the HHU is the ideal care service to implement and monitor it. Here we present a broad and recent series of paediatric patients with underlying chronic disease who received parenteral treatment at home.

The disease distribution found in our study diverges from that described in other series. In our study, 74.5% of the patients had respiratory tract superinfections, contrary to what has been reported in other publications in which osteoarticular10,11 or soft tissue12 infections were more prevalent. This is due to the chronic underlying disease in our patients, most of whom suffered from CF.

We wish to highlight that carers administered the treatment to most patients, which is why we could use drugs with a schedule of several doses a day. Under different arrangements, the patient needs to visit the emergency department daily for a nurse to administer the treatment,12 or the HHU travels daily to the home to administer it,13 so the most widely used drugs are those with a single-daily-dose schedule.

The antibiotics used most frequently these years were the same as those used by other groups, with third-generation cephalosporins and aminoglycosides being the most widely used. This is because most courses of antibiotherapy administered in the home were used in patients with CF.

As for the type of vascular access used, our data were consistent with most of the published literature14 that establishes peripheral access as the first choice. In case of complicated vascular access or in patients who are receiving frequent courses of antibiotics, a peripherally inserted central catheter or a conventional central catheter are used, although there is an increasing number of publications that propose the peripherally inserted central line as the first-choice route, presenting it as a safer, more effective, and less costly option.15,16

In our study, the rate of complications was 9.8%, far lower than rates reported in the literature.11,17,18 Consistent with the literature, the most frequent complications were extravasation or accidental displacement of the peripheral line, although the percentage was low in our sample, probably because most of our patients are older than 5 years. We did not register any other complications that, while infrequent, are reported in other studies, like neutropenia or fever.17

Our rate of episodes with favourable clinical outcome (90.2%) is very similar to what has been reported in the literature up to date.11,18 We should note that only 16 (9.8%) patients in our study required readmission, and that 12 (7.4%) of them required it unexpectedly for reasons related to their underlying disease, and not to therapeutic failure for the infection for which they were being treated.

Home administration of the prescribed treatment has several advantages. The most obvious advantage for patients is that they remain in their environment, and some can resume their school activities. In addition, evidence from various published studies show that this type of therapy increases the psychological wellbeing of paediatric patients,19 improves the physical, social, and emotional quality of life of adults,20 and results in a reduction in the number of nosocomial infections.21 The advantage over hospitalisation for providers is that they can treat patients in a pleasanter environment for latter, improving provider–patient communication and rapport. Lastly, it is advantageous for the administration, as it has been proven that OPAT results in fewer overnight stays at the hospital and lower costs for the hospital,22,23 in addition to increasing patient satisfaction.

Although at-home OPAT administered by the carers has been established as a safe, efficacious, practical, and cost-effective treatment option,24 and offers an alternative to patients who wish to return to their normal environment, which was supported by the results of our study, there are also disadvantages and risks. Some of these include the decreased ability to monitor the patient properly at home, the lower degree of supervision, the feelings of insecurity of carers at the beginning of treatment, and the medical complications that could arise in relation to the treatment. Although these are inherent risks in OPAT, our unit minimises them by the strict selection of patients and carers, offering intensive, problem-solving training during the hospital stay, and providing a quick means of communication between carers and the team in charge through the phone. Thus, the essential factors for a successful OPAT programme are: to have the appropriate infrastructure, to make a careful selection of patients, to have a multidisciplinary staff with experience both in at-home care delivery and in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases, to provide the necessary information and training, and to properly monitor the patient who is receiving this type of treatment. The hospital must guarantee continued care 24h a day to address any complications that may arise, and ideally there would be HHU coverage for most of these hours. Also, the HHU should work in close collaboration with the referring provider and with the infectious disease and pharmacy services.

There are a growing number of review studies on the home administration of parenteral treatment in children with acute disease such as osteomyelitis,25 cellulitis,26 pneumonia,27 or pyelonephritis.28

Our study has the following limitations: it is a single-centre study and the majority of referrals we receive are CF patients. These limitations may have resulted in biases in our analysis, which could be brought to light when comparing our results with those of other published studies.

This review and analysis has allowed us to identify areas where we are lacking, providing an incentive to try to design protocols based on scientific evidence and our clinical experience in the near future that would include not only patients with underlying chronic disease, but also patients with acute disease that could receive parenteral antimicrobial treatment at home.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Peláez Cantero MJ, Madrid Rodríguez A, Urda Cardona AL, Jurado Ortiz A. Tratamiento antimicrobiano parenteral domiciliario: análisis prospectivo de los últimos 12 años. Anal Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:86–91.