Understanding the characteristics and implications of the use of baby carriers can help health care providers understand the habits of their patients and provide guidance to improve quality of life in both children and caregivers. The aim of our study was to design and validate the first self-administered questionnaire to assess babywearing habits and their impact on health and physical activity as a means to monitor musculoskeletal complaints in caregivers.

Material and methods350 individuals who currently used or had used baby carrying systems in the last 10 years completed the questionnaire, which was previously subject to a pilot study in a panel of experts. We used exploratory factor analysis to assess the validity of the internal structure of the questionnaire. The Cronbach α coefficient was used to assess reliability. We used varimax rotation to improve the interpretation of the extracted factors.

ResultsThe factor analysis showed that the questionnaire is appropriate for measuring the dimensions or carriage factors established a priori. It extracted 3 factors each for the constructs of duration and weight of carriage, motivation, exercise habits and effects on infant health and 2 factors for caregiver pain that explained between 55% and 72% of the variance in each construct. The Cronbach α values were greater than 0.5.

ConclusionsThe results support the validity of the questionnaire and demonstrate that it is useful for its intended purpose.

Conocer las características y las repercusiones del uso de portabebés puede ayudar a los servicios de salud a comprender los hábitos de sus pacientes y aportar consejo para mejorar la calidad de vida de niños y personas porteadoras. El objetivo de este estudio fue diseñar y validar la primera encuesta autoadministrada que mida los hábitos de porteo, y la repercusión que tienen para la salud y el ejercicio físico como medio de control de dolencias musculoesqueléticas de las personas cuidadoras.

Material y métodos350 personas que utilizan o han utilizado en los últimos 10 años sistemas de transporte de bebés mediante porteo, completaron la encuesta, pilotada previamente en un panel de expertos. Se utilizó un análisis factorial exploratorio para obtener pruebas de la validez de la estructura interna de la encuesta. La fiabilidad fue evaluada mediante el coeficiente α de Cronbach. La interpretación de los factores extraídos se mejoró mediante la rotación varimax.

ResultadosEl análisis factorial mostró que el cuestionario es apropiado para medir las dimensiones o factores del porteo diseñadas a priori. Extrajo tres factores cada uno para los constructos de tiempo y carga del porteo, motivación, hábitos de ejercicio y efectos en la salud del bebé, y dos en relación al dolor de la persona cuidadora, que explicaban entre el 55% y 72% de la varianza en cada constructo. Los valores a α de Cronbach fueron superiores a 0,5.

ConclusionesLos resultados avalan la validez del cuestionario y que es útil para el objetivo propuesto.

The industry and the market around childbirth and infant care generate a growing number of products for parents. This is the case of babywearing systems, the use of which is increasing at a fast pace. Knowing the characteristics and potential repercussions of babywearing can help pediatrics, obstetrics and midwifery providers to understand the habits of their patients and provide guidance on the use of these products.

Babywearing is perceived as a means of transporting the baby that ensures constant contact between the child and the caregiver with several benefits for both. Chief among them are promoting safe attachment and facilitating breastfeeding, preventing plagiocephaly and protecting the developing spine and hips of the infant, among others.1

Despite the advantages and potential consequences of this practice, there is no evidence describing the characteristics of the daily use of baby carriers, the habits of caregivers or how caregivers perceive the impact of these products on their and their babies’ health. In fact, most of the studies that have assessed the biomechanical repercussions of baby carrier use have been conducted in dummies, which makes it difficult to know their performance in real-world conditions.2–9

The real-world evidence currently available chiefly consists of epidemiological studies on accidents associated with baby carrying systems. In this regard, in the United States, 19.5% of nursery product-related injuries have been found to be associated with baby carriers, and falls are the most frequent mechanism of injury.10 Cutaneous lesions have also been described.11

Still, while there may be benefits to babywearing, it places an additional load on the body of the carrier. Previous studies that have analysed different babywearing modalities have found that there are changes in posture12 that are particularly significant in the shoulder and pelvis angles.3 Furthermore, during walking, there are postural changes in the head and shoulders.3 In addition, changes in foot pressure increase when baby carriers are worn loosely.4 The changes in gait are also associated with an increased vertical ground reaction force and back extension compared to the unloaded gait.5 From a kinematic and biomechanical perspective, babywearing is closer to unloaded conditions compared to carrying the baby in the arms.6,7 However, both loading conditions (babywearing and in-arms holding of baby) increase the loading knee moments.7

The changes resulting from babywearing are also detectable at the level of muscle activity, and different types of baby carriers are associated with different electromyographic patterns.13 As regards the respiratory response, respiratory parameters increase, although without differences based on the type of baby carrier.8 But locomotory costs increase more when the baby is carried in arms compared to in a carrier.9 Just as there are biomechanical changes with the carrying of a load, there may be associated pain processes. In fact, a study found that the proportion of participants that developed pain was the same in the unloaded condition and with the use of a baby carrier and greater when the load was carried in arms.6

A review of the literature demonstrated the lack of a validated questionnaire to assess babywearing habits and their association with physical activity and the health of both child and caregiver. Therefore, the aim of our study was to develop and validate the first questionnaire to measure babywearing habits, their potential impact on the health of the carrier and the child and physical activity as a measure to control musculoskeletal pain in caregivers.

Material and methodsThe first step in the development of the questionnaire was a review of the literature on the use of baby carrier systems, physical, musculoskeletal and h result from the use of these devices, and the physical activity (regular and structured) habits and use of baby carriers. We analysed review studies and original studies to identify by consensus the most relevant aspects that should be included in the questionnaire.1–3,6,8,9,12,13 The contents were subsequently modified based on the results of the face validity assessment by a panel of experts, the field testing and the pilot study, after which the definitive version of the questionnaire was produced: Hábitos, repercusiones para la salud y ejercicio físico como medio de control de dolencias músculoesqueléticas del cuidador/a. (Habits, health repercussions and physical activity for control of musculoskeletal pain in the caregiver, CHABES-PORT).

Validation of the questionnaireIt was conducted in several phases14–16:

- -

Face validity: the assessment of face validity and the appropriateness of the content was carried out by a panel of experts comprising 6 specialists in sports science, health sciences, instructors, computer scientists and baby carrier testers, who revised the original draft of the questionnaire.

- -

Field testing: After validation by the panel of experts, 10 individuals who fit a particular profile completed the questionnaire. Specifically, we selected caregivers of infants or young children who were currently using baby carriers or had used them in the past, with a secondary or university education, including individuals who had carried 2 children in the same or different time periods. We requested their feedback on aspects such as changes in the wording of items that could improve their comprehension, elimination of items, appropriate use of words, changes to the format, and whether the time we had estimated it would take to complete the questionnaire was accurate in reality.

- -

Pilot study: after the revision of the items based on the feedback from field testing, we conducted a pilot study on a nonprobability sample of 350 caregivers recruited by distributing the self-report questionnaire (online) (Appendix B) through parenting associations and other social networks. After obtaining the responses, we assessed the internal validity and reliability of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire is intended for parents or caregivers who have had or cared for one or more babies in the past 10 years and used some kind of babywearing system.

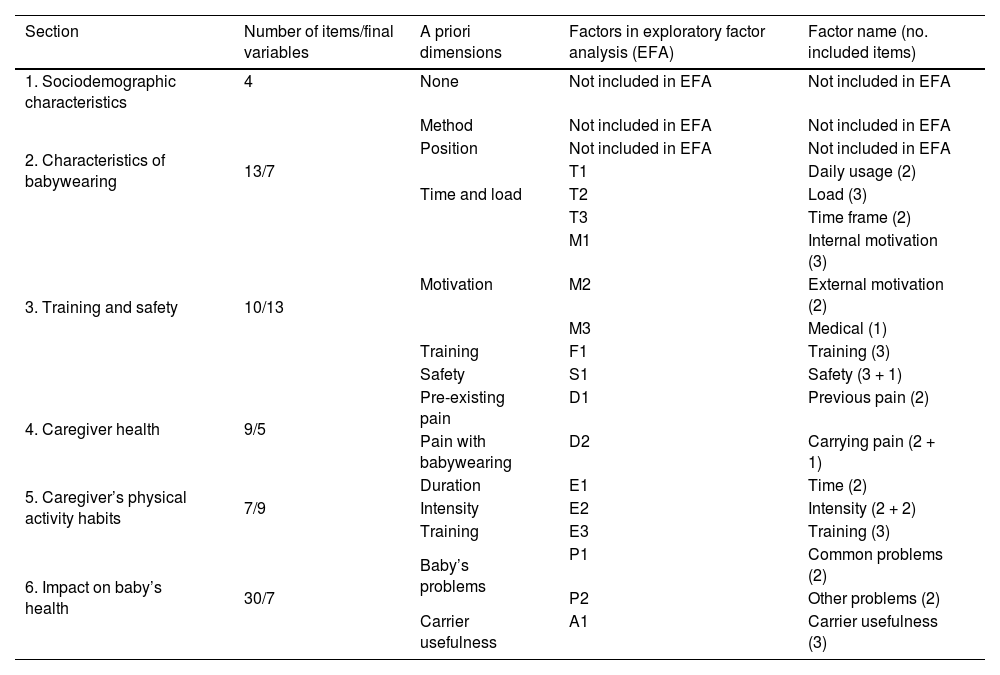

The questionnaire consists of 73 questions grouped into 6 sections. Table 1 summarizes the contents of each section. Section 1 comprises 4 items concerning sociodemographic characteristics. Section 2 comprises 13 items on the characteristics of babywearing. Section 3 (10 items) assesses aspects related to training in babywearing and safety aspects. Section 4 (9 items) collects information on the characteristics of babywearing.

Original structure of the questionnaire, including the a priori dimensions and the dimensions obtained in the exploratory factor analysis.

| Section | Number of items/final variables | A priori dimensions | Factors in exploratory factor analysis (EFA) | Factor name (no. included items) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sociodemographic characteristics | 4 | None | Not included in EFA | Not included in EFA |

| 2. Characteristics of babywearing | 13/7 | Method | Not included in EFA | Not included in EFA |

| Position | Not included in EFA | Not included in EFA | ||

| Time and load | T1 | Daily usage (2) | ||

| T2 | Load (3) | |||

| T3 | Time frame (2) | |||

| 3. Training and safety | 10/13 | Motivation | M1 | Internal motivation (3) |

| M2 | External motivation (2) | |||

| M3 | Medical (1) | |||

| Training | F1 | Training (3) | ||

| Safety | S1 | Safety (3 + 1) | ||

| 4. Caregiver health | 9/5 | Pre-existing pain | D1 | Previous pain (2) |

| Pain with babywearing | D2 | Carrying pain (2 + 1) | ||

| 5. Caregiver’s physical activity habits | 7/9 | Duration | E1 | Time (2) |

| Intensity | E2 | Intensity (2 + 2) | ||

| Training | E3 | Training (3) | ||

| 6. Impact on baby’s health | 30/7 | Baby’s problems | P1 | Common problems (2) |

| P2 | Other problems (2) | |||

| Carrier usefulness | A1 | Carrier usefulness (3) |

Section 5 (7 items) collects information on the caregiver's regular and structured physical exercise habits. Lastly, section 6, with 30 items, addresses the characteristics of babywearing in relation to the baby’s health, and it can be completed for 1 or 2 children carried by the same caregiver.

Assessment of internal validity and reliabilityTo assess the validity of the internal structure of the questionnaire, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis for each of the sections (excluding the first one) with the aim of identifying their underlying structure. We determined whether the data were suitable for factor analysis using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO > 0.5) and Bartlett sphericity tests (setting the level of significance at 0.05). We extracted the factors using principal component analysis and retained those with an eigenvalues greater than 1. The interpretation of the extracted factors was enhanced by varimax rotation. We assessed the internal consistency of each section by means of the Cronbach α coefficient, defining validity as a value greater than 0.5. The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc. 2003, Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsOf all respondents, 98% were female and 2% male, and 98% were of Spanish origin. Seventy-five percent had a university degree, 22% had completed secondary education and 3% had completed primary education. The mean age was 34.8 years (SD, 4.6).

The results of factor analysis demonstrated that the questionnaire is appropriate for assessing the dimensions or factors of babywearing designed a priori by the experts and revealed that some dimensions could be subdivided into more specific factors.

On the whole, the questionnaire was not designed with the aim of producing an additive scale for measuring the dimensions of babywearing, but rather as a set of variables that characterize the different dimensions of this practice. As a result, the initial number of items in the questionnaire and the final number of variables included in the factor analysis of each dimension did not always coincide (we excluded nominal variables with mutually excluding categories and variables concerning subsets of the population that would have resulted in an excessively small sample size; for items with a multiple choice-multiple answer format, responses were coded as 0–1; diagnosis and treatment variables were combined into a single ordinal variable). Similarly, for the calculation of the Cronbach α, we excluded variables which, due to their value formats or directionality could distort the comparison to a hypothetical overall analysis of the section. With these adjustments, we obtained significant results in the Bartlett test and KMO values greater than 0.5 for every section of the questionnaire (range, 0.567−0.682), which confirmed the suitability of the data to conduct the exploratory factor analysis for all dimensions. In addition, in the internal consistency assessment we obtained α values ranging from 0.512 (section 5) to 0.676 (section 4) (Table 1).

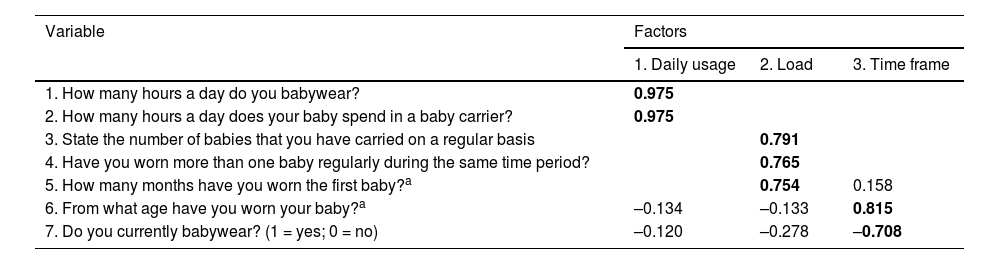

Table 2 presents the results of the factor analysis of section 2 (Characteristics of babywearing). The analysis included the responses of 347 participants for 7 of the 13 variables, as we excluded the items on the type of baby carrier and the position in which it was used (nominal variables) and variables regarding babywearing in a second child. We identified 3 factors that explained 71.75% of the variance. The first factor included 2 variables concerning the amount of time a day that the respondent used the baby carrier, the second factor included 3 variables related to the load added to the carrier, and the third factor included 2 variables concerning whether the respondent was currently or was no longer using a baby carrier. The Cronbach α was 0.574. We excluded the items “How long have you been babywearing?” and “From what age have you worn your baby?”, the values and directionality of which, respectively, invalidated the reliability assessment.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of section 2. Characteristics of babywearing.

| Variable | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Daily usage | 2. Load | 3. Time frame | |

| 1. How many hours a day do you babywear? | 0.975 | ||

| 2. How many hours a day does your baby spend in a baby carrier? | 0.975 | ||

| 3. State the number of babies that you have carried on a regular basis | 0.791 | ||

| 4. Have you worn more than one baby regularly during the same time period? | 0.765 | ||

| 5. How many months have you worn the first baby?a | 0.754 | 0.158 | |

| 6. From what age have you worn your baby?a | –0.134 | –0.133 | 0.815 |

| 7. Do you currently babywear? (1 = yes; 0 = no) | –0.120 | –0.278 | –0.708 |

Total explained variance: 71.75%.

Bartlett sphericity test: χ2 = 848.626; 21 df; P < .001; KMO = 0.567; α de Cronbach = 0.574.

The highest correlations between the original variables and the factor onto which they loaded are presented in boldface.

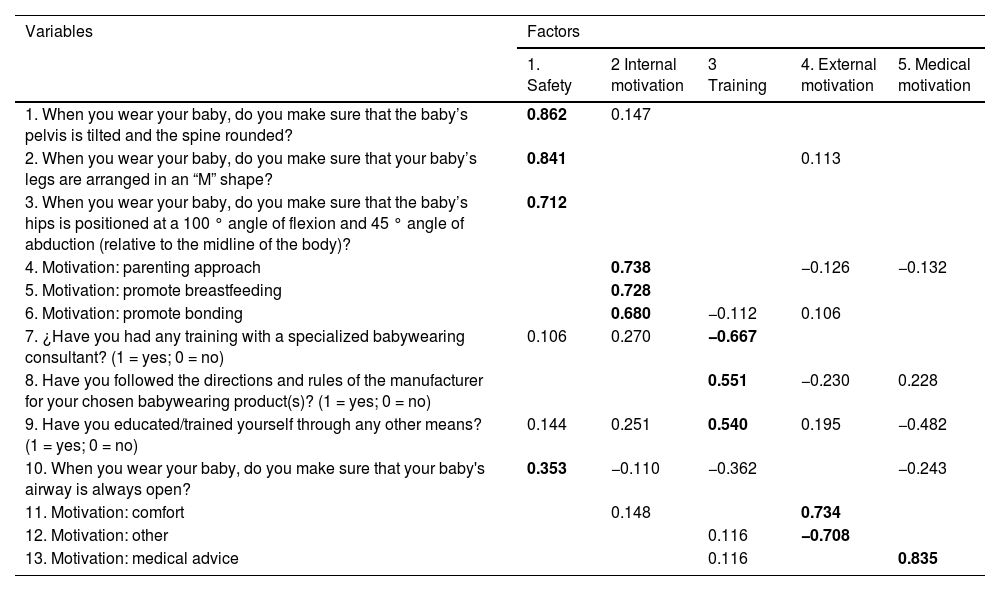

Table 3 presents the results of the factor analysis of section 3 (Training and Safety). This dimension comprised 13 variables (the item regarding the motivation for babywearing produced six 0–1 variables) assessed in the entire sample (n = 350). The analysis identified 5 factors that explained 56.91% of the variance. With respect to the dimensions established a priori, motivation was subdivided into 3 factors, which we labeled internal, external and medical based on what they referred to. The factor that explained the largest amount of the variance was the safety factor, which clearly included 3 of the 4 items included to assess this aspect. However, the item “When you wear your baby, do you make sure that your baby’s airway is always open?” loaded onto both the Safety and the Training factors. For the sake of consistency, we kept it in the former. The Training factor included 3 items. The Cronbach α for the overall section was 0.574.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of section 3. Training and safety.

| Variables | Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Safety | 2 Internal motivation | 3 Training | 4. External motivation | 5. Medical motivation | |

| 1. When you wear your baby, do you make sure that the baby’s pelvis is tilted and the spine rounded? | 0.862 | 0.147 | |||

| 2. When you wear your baby, do you make sure that your baby’s legs are arranged in an “M” shape? | 0.841 | 0.113 | |||

| 3. When you wear your baby, do you make sure that the baby’s hips is positioned at a 100 ° angle of flexion and 45 ° angle of abduction (relative to the midline of the body)? | 0.712 | ||||

| 4. Motivation: parenting approach | 0.738 | −0.126 | −0.132 | ||

| 5. Motivation: promote breastfeeding | 0.728 | ||||

| 6. Motivation: promote bonding | 0.680 | −0.112 | 0.106 | ||

| 7. ¿Have you had any training with a specialized babywearing consultant? (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.106 | 0.270 | −0.667 | ||

| 8. Have you followed the directions and rules of the manufacturer for your chosen babywearing product(s)? (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.551 | −0.230 | 0.228 | ||

| 9. Have you educated/trained yourself through any other means? (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.144 | 0.251 | 0.540 | 0.195 | −0.482 |

| 10. When you wear your baby, do you make sure that your baby's airway is always open? | 0.353 | −0.110 | −0.362 | −0.243 | |

| 11. Motivation: comfort | 0.148 | 0.734 | |||

| 12. Motivation: other | 0.116 | −0.708 | |||

| 13. Motivation: medical advice | 0.116 | 0.835 | |||

Total explained variance: 56.91%.

Bartlett sphericity test: χ2 = 530.325; 78 df; P < .001; KMO = 0.636; Cronbach α = 0.532.

The highest correlations between the original variables and the factor onto which they loaded are presented in boldface.

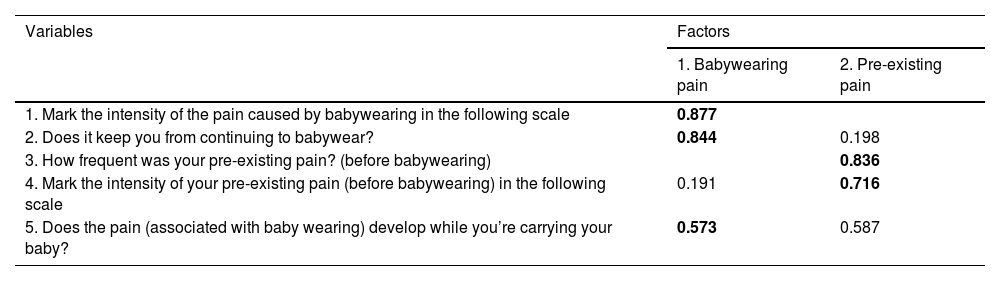

Table 4 presents the results of the factor analysis of section 4 (Caregiver health). The analysis included 5 variables applicable only to caregivers that reported pain (n = 32). It identified 2 factors that explained 68.83% of the variance. The first one (Babywearing pain) included 2 variables associated with pain developed during babywearing and the second one (Pre-existing pain) another 2 variables associated with pain that developed before using a baby carrier. Does the pain (associated with baby carrier) develop while you’re wearing your baby? loaded onto both factors, and, for the sake of consistency, remained in the first one. The hypothetical elimination of this item would result in a lower Cronbach α, and the overall Cronbach α value for the 5 included variables was 0.676.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of section 4. Caregiver’s health.

| Variables | Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Babywearing pain | 2. Pre-existing pain | |

| 1. Mark the intensity of the pain caused by babywearing in the following scale | 0.877 | |

| 2. Does it keep you from continuing to babywear? | 0.844 | 0.198 |

| 3. How frequent was your pre-existing pain? (before babywearing) | 0.836 | |

| 4. Mark the intensity of your pre-existing pain (before babywearing) in the following scale | 0.191 | 0.716 |

| 5. Does the pain (associated with baby wearing) develop while you’re carrying your baby? | 0.573 | 0.587 |

Total explained variance: 68.83%.

Bartlett sphericity test: χ2 = 32.439; 10 df; P < .001; KMO = 0.682; α de Cronbach = 0.676.

The highest correlations between the original variables and the factor onto which they loaded are presented in boldface.

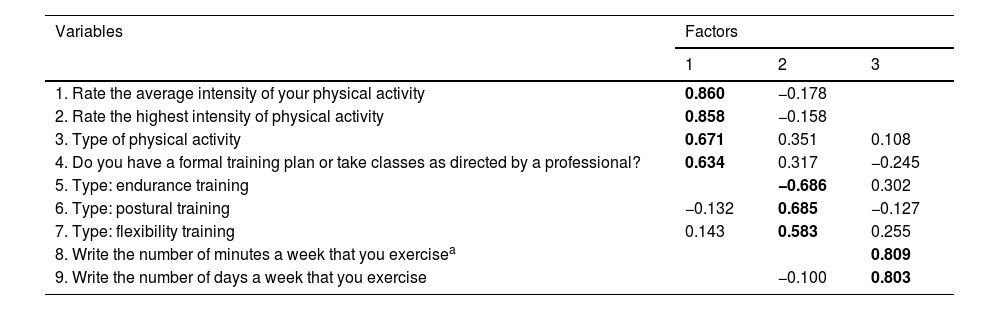

Table 5 presents the results of the factor analysis of section 5 (Caregiver’s physical activity habits). The analysis included 9 variables applicable to caregivers who exercised regularly (n = 149). It identified 3 factors that explained 61.07% of the total variance. The 3 factors coincided with the dimensions that had been established a priori: time (frequency and duration), intensity and type. The first identified factor was intensity, which included 4 variables, the second was the type of physical activity, with 3 variables, and the third included 2 variables to assess the frequency and duration of exercise. It is worth noting that the variable concerning strength training loaded on the intensity factor. For the reliability analysis, we excluded the item “Write the number of minutes a week that you exercise”, and we obtained a Cronbach α of 0.512.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of section 5. Caregiver’s physical activity habits.

| Variables | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1. Rate the average intensity of your physical activity | 0.860 | −0.178 | |

| 2. Rate the highest intensity of physical activity | 0.858 | −0.158 | |

| 3. Type of physical activity | 0.671 | 0.351 | 0.108 |

| 4. Do you have a formal training plan or take classes as directed by a professional? | 0.634 | 0.317 | −0.245 |

| 5. Type: endurance training | −0.686 | 0.302 | |

| 6. Type: postural training | −0.132 | 0.685 | −0.127 |

| 7. Type: flexibility training | 0.143 | 0.583 | 0.255 |

| 8. Write the number of minutes a week that you exercisea | 0.809 | ||

| 9. Write the number of days a week that you exercise | −0.100 | 0.803 | |

Total explained variance: 61.07%.

Bartlett sphericity test: χ2 = 298.961; 10 df; P < .001; KMO = 0.623; α de Cronbach = 0.512.

The highest correlations between the original variables and the factor onto which they loaded are presented in boldface.

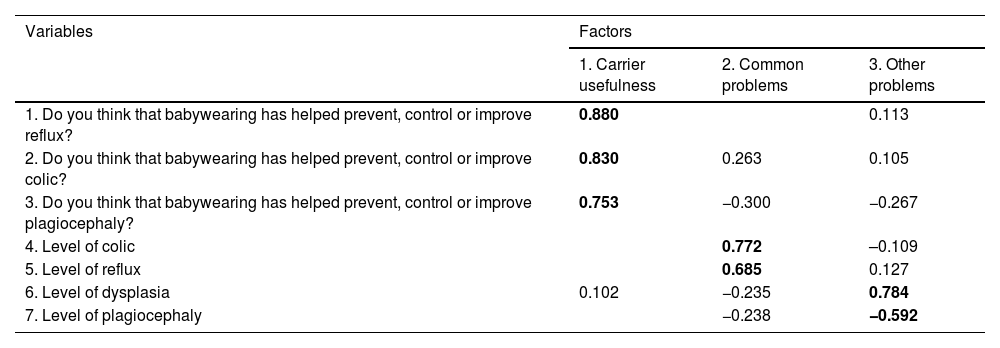

Table 6 presents the results of the factor analysis of section 6, last in the questionnaire (Impact of babywearing on the health of the baby). It included 7 variables applicable to the entire sample (n = 350). Four of them (level of colic, level of reflux, level of dysplasia and level of plagiocephaly) resulted from recording the items “Has your baby received a diagnosis of …?”, “Has your baby received treatment for…?”) into a composite ordinal variable with 3 levels (0 = not diagnosed; 1 = yes, diagnosed but not treated; 2 = yes, diagnosed and treated) for each of the considered problems in the baby: reflux, colic, plagiocephaly and hip dysplasia. We eliminated the variable concerning falls or injuries in the baby associated with babywearing because there was only one such case. We also excluded from the analysis all items concerning the second child and nominal variables with several categories. We identified 3 factors that explained 63.97% of the total variance. The first factor included 3 variables concerning the perceived benefits of babywearing on the child’s health. The next 2 factors were associated with the a priori dimension “Baby’s problems” (Table 1). Each included 2 variables and, based on their content, we labeled them “common problems” and “other problems”. The Cronbach α for the overall section was 0.559.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis of section 6. Impact on baby’s health.

| Variables | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Carrier usefulness | 2. Common problems | 3. Other problems | |

| 1. Do you think that babywearing has helped prevent, control or improve reflux? | 0.880 | 0.113 | |

| 2. Do you think that babywearing has helped prevent, control or improve colic? | 0.830 | 0.263 | 0.105 |

| 3. Do you think that babywearing has helped prevent, control or improve plagiocephaly? | 0.753 | −0.300 | −0.267 |

| 4. Level of colic | 0.772 | –0.109 | |

| 5. Level of reflux | 0.685 | 0.127 | |

| 6. Level of dysplasia | 0.102 | −0.235 | 0.784 |

| 7. Level of plagiocephaly | −0.238 | −0.592 | |

Total explained variance: 63.97%.

Bartlett sphericity test: χ2 = 398.767; 21 df; P < .001; KMO = 0.568; α de Cronbach = 0.559.

The highest correlations between the original variables and the factor onto which they loaded are presented in boldface.

We found that the profile of caregivers that practiced babywearing in this survey was a Spanish woman aged 35 years with a university education. Overall, the developed questionnaire seemed useful for assessing the dimensions of babywearing, although the different dimensions were characterized by a different set of variables. There are no previous studies specifically defining or exploring the structure of these dimensions, and due to this gap in the evidence, we conducted an exploratory rather than a confirmatory factor analysis.17,18

Babywearing is an increasingly widespread practice, yet, to our knowledge, this is the first questionnaire developed for this purpose.

With the exception of 2 dimensions of the construct related to the characteristics of babywearing section, associated with method and position, the clustering pattern of the 11 dimensions resulted in 16 factors in the exploratory factor analysis. Moreover, the factors associated with each section could explain a large percentage of the variance.

Given the relative freedom exercised in selecting items for the questionnaire, we found that the final version of some of its sections (sections 2 and 6) differed quite a lot in terms of the initial number of variables the variables eventually retained in the factor analysis, although it did not negatively affect the relevant information. In this regard, we must highlight section 6 on the impact on the baby’s health, which initially comprised 30 items in 2 a priori dimensions (with 15 items concerning the first baby worn by the respondent) and ended up structured into 7 items loading into 3 factors in the exploratory factor analysis.

We want to underscore the external validity of the results, as the questionnaire was administered and validated in a sample of individuals that used baby carriers within the past 10 years, so the findings can be directly extrapolated to this subset of the population.

As regards the methodological limitations of the study in relation to the instrument used for data collection and its validation process, the main one was the lack of measures developed for the same purpose, which precluded validation through comparison with similar instruments. In addition, the questionnaire was not designed as a scale, which affected the internal consistency analysis by means of the Cronbach α. There is also a risk of information bias19 arising from the subjective perceptions of the baby carrier users, especially in regard to training and baby safety. In addition, while the questionnaire was validated in women, the small number of male participants may limit the application of this instrument in this subset of the population.

Despite the limitations we have just mentioned, the design and validation strategy adhered to current recommendations.20,21 The sample recruited for the validation process was large and sufficiently representative of the target population. The simplicity of the wording and the dichotomous answer format of most items make the application of this instrument in health care facilities, different countries and in individuals with varying educational attainment.

In conclusion, we consider this questionnaire quick and easy to complete and, based on the results of the validation process, also sufficiently rigorous to assess habits, health and physical activity in relation to the practice of babywearing. Using it will allow obtaining better statistics on the ergonomics and health of children and caregivers and the detection of favorable and unfavorable habits associated with babywearing. It can also be used to assess whether regular physical exercise can have a protective effect on the health of carriers. Such information can guide the development of recommendations for babywearing as well as improved health education interventions so that the use of baby carriers can be safer and more beneficial.

Ethical considerationsAll participants were informed about the study and provided consent for the use of the resulting data. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Education Sciences and Sports of the Universidad de Vigo (Ref: 10-280722).

We thank all the participants for their valuable feedback and contribution to this study.