There are various scales designed to determine the risk of malnutrition at hospital admission in children. However, most of these instruments are developed and published in English. Their cross-cultural adaptation and validation being mandatory in order to be used in our country.

ObjectivesCross-culturally adapt three scales designed to determine the risk of malnutrition linked to the disease and determine the validity of their content.

Material and methodsCross-cultural adaptation using the translation-back-translation method in accordance with the recommendations of the International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. Content validity was measured by a panel of experts (under seven basic selection criteria adapted from the Fehring model) who evaluated each item of the scales by measuring 4 criteria: ambiguity, simplicity, clarity and relevance. With the extracted score, Aiken’s V statistic was obtained for each item and for the complete scales.

ResultsStarting from three independent translations per scale, 3 definitive versions in Spanish of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP scales were obtained semantically equivalent to their original versions. The PNRS and STRONGkids scales presented an Aiken’s V greater than 0.75 in all their items, while the STAMP scale presented a value less than 0.75 for the item “weight and height”.

ConclusionThis study provides the transculturally adapted Spanish versions of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP scales. The PNRS and STRONGkids scales present valid content to be applied in the state hospital context. STAMP requires the adaptation of its item “weight and height” to consider its use in a Spanish child population adequate.

Existen diversas escalas diseñadas para determinar el riesgo de desnutrición al ingreso hospitalario en población infantil, sin embargo, la mayor parte de estos instrumentos se desarrollan y publican en lengua inglesa, siendo preceptiva su adaptación transcultural y validación para poder ser utilizados en nuestro país.

ObjetivosAdaptar transculturalmente 3 escalas diseñadas para determinar el riesgo de desnutrición ligada a la enfermedad y determinar la validez de su contenido.

Material y métodosAdaptación transcultural mediante el método de traducción-retrotraducción de acuerdo con las recomendaciones de la International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. Se midió la validez de contenido a través de un panel de expertos (bajo 7 criterios básicos de selección adaptados del modelo Fehring) que evaluaron cada ítem de las escalas midiendo 4 criterios: ambigüedad, sencillez, claridad y relevancia. Con la puntuación extraída se obtuvo el estadístico V de Aiken para cada ítem y para las escalas completas.

ResultadosPartiendo de 3 traducciones independientes por escala se obtuvieron 3 versiones definitivas en castellano de las escalas PNRS, STRONGkids y STAMP semánticamente equivalentes a sus versiones originales. Las escalas PNRS y STRONGkids presentaron una V de Aiken superior a 0,75 en todos sus ítems, mientras que escala STAMP presentó un valor inferior a 0,75 para el ítem «peso y altura».

ConclusiónEste estudio aporta las versiones en castellano adaptadas transculturalmente de las escalas PNRS, STRONGkids y STAMP. Las escalas PNRS y STRONGkids presentan un contenido válido para ser aplicadas en el contexto hospitalario estatal. STAMP requiere la adaptación de su ítem «peso y altura» para considerar adecuado su uso en población infantil española.

Malnutrition associated with disease is a clinical problem that has an impact on child health in the short and the long term (affecting psychomotor and cognitive development, increasing the incidence of infectious diseases and reducing quality of life).1,2

Among the different adverse effects associated with hospitalization, nosocomial malnutrition is defined as a nutritional imbalance acquired during the hospital stay that may occur whether or not the patient had malnutrition prior to admission.3

From an epidemiological perspective, in developed countries the incidence of acute malnutrition during hospitalization is estimated at 13.5%–44.5% if we apply the definition of a loss of more than 2% of the body weight4,5 and 3%–25.4% applying the definition of weight loss greater than 5%.6,7

Undernutrition during hospitalization is associated with increases in the length of stay,5 the incidence of comorbidities and the mortality risk.8 Thus, interventions need to be implemented for assessment of nutritional status at admission and early detection of patients at risk.9 At present, the assessment of the risk of malnutrition associated with disease and hospitalization is largely based on the use of scales designed for the purpose.10 However, most of these instruments were developed and published outside of Spain and in English, and therefore they need to be subjected to a transcultural adaptation process so that they can be applied in our country.11

Our objective was to carry out the transcultural adaptation of the 3 most widely used scales developed to determine the risk of undernutrition in hospitalised children: the Pediatric Nutritional Risk Score (PNRS),4 the Screening Tool for Risk on Nutritional status and Growth (STRONGkids)7 and the Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatric (STAMP)12 to obtain versions in Spanish semantically equivalent to the originals in terms of constructs and content.

Material and methodsWe undertook a transcultural adaptation process through the forward-backward translation method following the recommendations of the International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests.13 We obtained permission from the 3 authors of the original PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP instruments to develop the transcultural adaptation for Spain.

The original version of each of the instruments was translated independently by 3 translators (one with a degree in English philology, one with a degree in translation and interpretation, and a translator from the United Kingdom), who were instructed to prioritise semantic equivalence to the original version as opposed to literal translation.

The 9 translations (3 per scale) were sent to a panel of experts, who were asked to assess which translation they considered most appropriate and to modify if needed words or expressions that they thought could be improved, emphasising that new concepts should not be introduced under any circumstances. After an analysis that was both quantitative (number of experts that agreed on the same translation) and qualitative (feedback and modifications proposed by the panel), the research team established the 3 definitive versions of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP scales in Spanish. These 3 versions were subjected to back translation to the original language of the scale, performed by a company specialised in translation of scientific texts, from which we requested an assessment of the semantic equivalence in which the words that did not appear in the back translation but did appear in the original version were highlighted.

To assess content validity, we had an expert panel evaluate the definitive versions in Spanish and complete an ad-hoc questionnaire that assessed each item of each scale based on 4 criteria: ambiguity, simplicity, clarity and relevance. Each criterion was rated on a Likert scale that ranged from 1 to 4. We applied the Aiken formula to the resulting scores, obtaining values ranging from 0 to 1.14 We considered Aiken V values greater than 0.75 indicative of adequate content validity.15

We estimated that 5–10 experts were needed to carry out the transcultural adaptation process.16 In the case of the content validity, we deemed that we needed a panel of 10 experts.15 Panels were formed including experts from different fields (paediatricians/paediatric gastroenterologists, nutritionists and nurses) from different health care institutions. The status of expert was determined applying 7 selection criteria adapted from the Fehring model17: occupation as a health professional specialised in paediatrics (paediatrician, paediatric nurse) (3 points), holding a master’s or doctorate degree (1 point), having developed a thesis relevant to the subject under study (2 points), having published an article relevant to the subject matter in a peer-reviewed journal (2 points), membership in a recognised research group or research experience in an area relevant to the subject matter (2 points), clinical experience in paediatrics of at least 5 years (2 points) and at least 1 year of professional experience in child nutrition (2 points). The minimum score to be considered an expert was 5 points.

From an ethical standpoint, we considered that completion of these assessments by the expert implied consent to the use of the provided information. The project was approved in the framework of the project “Adaptación transcultural y validación de tres scores para la detección de riesgo de desnutrición pediátrica durante la hospitalización (PNRS, STAMP y STRONGkids). Estimación de la incidencia de desnutrición)” by both the Ethics and Methods Committee of the Instituto de Investigación Clínica of the Department (May 28, 2015) and the Academic Committee of the Doctorate Programme of the School of Medicine (July 12, 2016).

ResultsForward and backward translation processWe obtained a total of 7 expert assessments for each of the 3 independent translations of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP scales. Table 1 presents the most frequent observations of the experts regarding semantic equivalence.

Observations made by experts in the process of translating the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP.

| Translation | Observation |

|---|---|

| Dieta asignada | Dieta recomendada. Requerimientos dietéticos |

| Indicio de dolor | Signo de dolor. Tipo de dolor |

| Condiciones médicas | Situación clínica |

| Intervención visceral mayor | Intervención quirúrgica mayor or cirugía visceral mayor |

| Implicaciones nutricionales definidas | Implicaciones nutricionales seguras. Consecuencias nutricionales definidas. Repercusiones nutricionales definidas. Implicaciones nutricionales precisas |

| Ingesta nutricional | Ingesta. Ingesta de nutrientes. Ingesta dietética |

| Rostro demacrado | Cara delgada, flaca, enjuta, magra, escuchimizada, consumida, esquelética |

| Ingesta nutricional pobre | Ingesta nutricional escasa. Reducción de la ingesta. Ingesta escasa. Escasa ingesta nutricional |

| Tablas de referencia | Percentiles de referencia. Tablas de crecimiento, tablas de referencia rápida de percentiles |

| Espacios percentiles/espacios de centiles | Espacios entre curvas de percentiles. Espacios entre percentiles. Espacios en los percentiles |

| Riesgo de malnutrición | Riesgo de desnutrición |

| Intervención nutricional preexistente | Sigue recomendaciones dietéticas específicas |

| Investigaciones | Procedimientos diagnósticos. Pruebas diagnósticas. Exámenes complementarios |

| Ausencia de ganancia de peso | Estancamiento de peso |

| Ganancia inexistente de peso | |

| No aumento de peso | |

| Bebés <1 año | Lactantes <1 año |

| Infantes <1 año | |

| Niños <1 año |

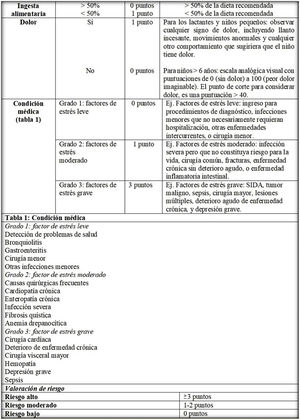

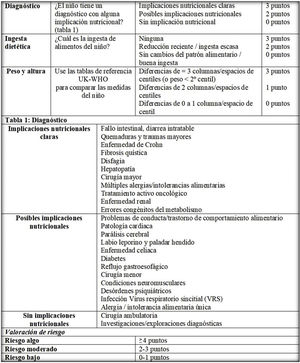

After we assessed the concordance between the wording of the different versions and applied the noted observations, the research team developed the definitive versions of the PNRS (Fig. 1), STRONGkids (Fig. 2) and STAMP (Fig. 3) scales after their transcultural adaptation and translation to Spanish.

The 3 definitive versions of the scales were submitted for backward translation, and adequate equivalence was found between the translations and the originals (a total of 9 words were identified in the original scales that were not included in the backward translations).

Content validation processWe obtained 10 content assessments for the Spanish versions of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP scales. Table 2 presents the Aiken V values obtained for each item and for the total scales.

Aiken V for estimating the content validity of the Spanish versions of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP.

| Instrument | Item | Mean (SD) | CV | 95% Ci |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNRS | Dietary intake | 3.72 (0.299) | 0.900 | 0.752−0.968 |

| Pain | 3.50 (0.565) | 0.833 | 0.664−0.926 | |

| Medical condition | 3.62 (0.412) | 0.873 | 0.711−0.950 | |

| Full scale | 3.61 (0.201) | 0.869 | 0.707−0.948 | |

| STRONGkids | Subjective clinical assessment | 3.50 (0.656) | 0.833 | 0.664−0.926 |

| Disease with risk of malnutrition | 3.62 (0.503) | 0.873 | 0.711−0.950 | |

| Dietary intake and nutrient losses | 3.60 (0.502) | 0.866 | 0.703−0.946 | |

| Weight loss or poor weight gain | 3.65 (0.579) | 0.883 | 0.723−0.956 | |

| Full scale | 3.59 (0.310) | 0.863 | 0.699−0.944 | |

| STAMP | Diagnosis | 3.60 (0.394) | 0.866 | 0.703−0.946 |

| Dietary intake | 3.75 (0.577) | 0.916 | 0.764−0.973 | |

| Weight and height | 2.80 (0.621) | 0.60a | 0.423−0.754 | |

| Full scale | 3.38 (0.356) | 0.793 | 0.619−0.900 |

Mean (SD): mean obtained through the assessment of the clarity, simplicity, ambiguity and relevance of the items by a Likert scale. The score for the full scale was obtained by obtaining the mean of the mean ratings of the individual items.

CI, confidence interval for the Aiken V statistic; CV, content validity obtained applying the Aiken formula.

Table 3 presents the Aiken V values obtained for each criterion and for each item of the scales.

Aiken V for each criterion and item of the Spanish versions of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP.

| Scale | Item | Relevant | Simple | Clear | Ambiguous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNRS | Dietary intake | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.8 |

| Pain | 0.866 | 0.866 | 0.766 | 0.833 | |

| Medical condition | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| STRONGkids | Subjective clinical assessment | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.833 | 0.80 |

| Disease with risk of malnutrition | 0.90 | 0.833 | 0.866 | 0.90 | |

| Dietary intake and nutrient losses | 0.90 | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.90 | |

| Weight loss or poor weight gain | 0.833 | 0.90 | 0.933 | 0.833 | |

| STAMP | Diagnosis | 0.966 | 0.866 | 0.833 | 0.8 |

| Dietary intake | 1 | 0.866 | 0.933 | 0.866 | |

| Weight and height | 0.8 | 0.533a | 0.5a | 0.566a |

CV, content validity obtained applying the Aiken formula.

In the validation of a scale, the first step is the transcultural adaptation of the original version. This requires permission from the author of the original scale, which in this case was granted by Dr. Isabelle Sermet-Gaudelus (PNRS), Dr. Jessie M. Hulst (STRONGkids) and Dr. Helen McCarthy (STAMP).

In this study, we initially conceived a simple transcultural adaptation process, as none of the 3 scales is large in terms of the number of items. However, since there were different interpretations of certain terms contained in the scales, interesting semantic discrepancies emerged in the adaptation process that required resolution prior to deciding on the final version in Spanish.

Since there were 3 translations per scale and 7 experts, we obtained at least 3 possible versions for each item of the scales and up to 5 different versions for items such as the weight and height in the STAMP. This fact foreshadowed the problems that would emerge with the use of this item in the Spanish adaptation.

Establishing the criterion based on which to determine the choice of one or another translated version was challenging, and we considered that the most comprehensive criterion would be the one combining both a quantitative aspect (number of experts advocating for a given version) and a qualitative aspect (observations made by the experts regarding the semantic content of the items and consultation of the definitions of the words in everyday language). For instance, in the PNRS we found issues with the operational definitions. For the item about dietary intake, we considered 3 completely different translations for the operational definition: “consumo <50% de la dieta asignada/dieta recomendada/requerimientos dietéticos”. The eventual selection for the definitive version of dieta recomendada (“recommended diet”) was based on the definition of the Real Academia Española of asignar as “señalar lo que corresponde a alguien o algo” (specifying what corresponds to someone or something) compared to the definition of recomendar as “aconsejar algo a alguien para bien suyo” (advise something to someone for their own good).

Compared to the other scales, we found fewer semantic dilemmas in the STRONGkids, during the transcultural adaptation. The only semantic dilemma was identified in the first item, which was translated as “grasa subcutánea disminuida” or “disminución de grasa subcutánea”. In the original version, this item has to be completed by clinicians based on their subjective judgment, which entails the need to know the previous status of the patient. As a general rule, it is assumed that health care providers (paediatricians, nurses, dietitians…) administering a scale are not aware of the previous condition of the patient, and thus this approach would require consulting the caregivers to make the assessment. In light of this issue, we chose to keep the version worded as “grasa subcutánea reducida” understood as a “small” amount of subcutaneous fat. When it comes to the STRONGkids, Ortiz-Gutierrez et al.18 had previously published a transcultural adaptation of it in Spanish for its use in Mexico: STRONGkids: tamiz de riesgo nutricional. We found substantial agreement between the two Spanish versions (with the exception of a few phrases: “se contempla una cirugía”, “días previos a la admisión”), which supports the Spanish version we obtained after its review and analysis. We ought to highlight that the version published by Ortiz-Gutierrez et al. included the expression “disminución/pérdida de grasa subcutánea y/o de masa muscular” in the subjective clinical assessment item (“Valoración clínica subjetiva”), despite noting that the item must be answered by the health care professional.18

As for the STAMP, several semantic dilemmas emerged, mainly concerning the “Weight and height” item. There was disagreement regarding the translation of the expression “growth chart or the centile quick reference tables”. The item refers to the United Kingdom-World Health Organization growth charts, which can be consulted at http://www.stampscreeningtool.org. We decided to keep the reference to growth charts or reference tables (“gráficas de crecimiento o las tablas de referencia”), as both formats may be used, but adding the qualification “UK-WHO” so clinicians will be aware of which tables or charts should be used if the original application were to be maintained.

In the content validity process, we obtained assessments from a total of 10 experts for each of the instruments. The highest content validity corresponded to the PNRS, followed by the STRONGkids, and both scales, as constructed or with slight modifications, were considered relevant to detect the risk of undernutrition in the Spanish paediatric inpatient population. When it came to the STAMP, while the Aiken V for the total scale was greater than 0.75, there was one item (weight and height) for which it was under 0.75, suggesting that in order to be used in the Spanish paediatric population, this item should be replaced by an equivalent item fitting the context in which the scale is applied.

When it comes to the PNRS, we believe it should be applied at 48 h from (a recommendation that was also given in the original study of the scale4) so that the assessment of intake during hospitalization be as little biased as possible. It is easier to apply in care settings that implement pain assessment. However, we believe it may also be useful in care settings whose culture does not include pain assessment, as it provides an opportunity to integrate it in care delivery. We definitely recommend the use of pain scales with a validated Spanish version to answer the pain item accurately. The classification of diseases included in the medical condition item (“Condición médica”) was significantly associated with a weight loss of more than 2% in the multivariate regression model of the original study of the PNRS scale,4 and therefore, we consider that this is an evidence-based classification that could, in any case, be expanded in future studies. Although the application of the PNRS at 48 h post admission may be a limitation, we think that it also offers significant advantages. It allows the care team to schedule the nutritional screening of the patient and to set up alerts in health information systems that would be triggered 48 h after admission. In addition, it would allow correction of potential dehydration/overhydration states affecting patient weight and assessment of how the child responds to the diet prescribed by the hospital. In addition, it can streamline the workloads of health care staff, as patients with stays of less than 48 h would not need to undergo the assessment.

The STRONGkids includes 2 items to be completed by the provider in charge of the patient (based on subjective clinical assessment and whether the patient has a disease associated with high nutritional risk) and another 2 to be completed by the primary caregiver of the child (about food intake/reduced intake and weight loss/poor weight gain).19 This involves a degree of subjectivity in the assessment by relatives and/or caregivers, which is also the case of other screening tools that, like the STRONGkids, are based on the guidelines of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN),20 which should be taken into account in the interpretation of results.

As for the STAMP, the most important aspect to consider is that the weight and height item received poor scores for clarity, feasibility and ambiguity. Some of the most frequent observations by experts were that the reference tables proposed for the original scale are not ideal for application to the Spanish paediatric population. In the original version, the weight and height item of the STAMP was to apply the UK90 reference tables,21 but the supplemental materials available on the website for the STAMP provide the UK-WHO growth tables, which mix anthropometric data for children aged 2 weeks to 4 years from the WHO 2006 and UK90 standards.22 One expert in the panel considered that the growth reference to be used in completing this item should be specified, as the operational definition did not and that left open the possibility of using any of the existing standards. When it comes to the selection of the growth standard, we believe it would be logical to apply the one that is recommended for the setting or area where the scale is being applied and included in the corresponding health information system. In 2012, Lama et al. assessed the usefulness of the STAMP applying the growth tables for the Spanish population published by Hernández Castellet et al. in 198823 instead of the UK90, and found similar results in the distribution of nutritional risk (low risk: 18.8% [n = 47] with UK90 versus 20% [n = 50] with Hernández Castellet et al.; moderate risk: 32.8% [n = 82] versus 34.8% [n = 87]; high risk: 48.4% [n = 121] versus 45.2% [n = 113]).24 However, the authors did not provide data on the agreement between both classifications or the presence or absence of significant differences between the 2 distributions. Other studies conducted later in the Spanish population did not continue with this approach, and instead used the original version of the STAMP with the UK90 tables.25 We believe it is necessary to continue developing this type of alternatives in future studies to produce classifications based on reference tables used in our region to improve the content validity of the item. In addition, adapting the item to the growth standards of the WHO could be an interesting line of investigation, given their widespread use in clinical practice.26,27

ConclusionThis study contributes the transcultural adaptation and analysis of content validity of the PNRS, STRONGkids and STAMP instruments performed by experts of the subject with the approval of the original authors. We include the definitive versions of these instruments for potential application in the paediatric population of Spain, which may be of interest both for clinical practice and research purposes.

The Spanish version of the PNRS has valid content, in terms of the relevance, clarity, simplicity and absence of ambiguity of its items, to determine the risk of undernutrition in the Spanish population. It would require the inclusion in the operational definitions of validated scales in Spanish to assess pain in children aged 6 or more years and setting the timing of assessment of nutritional risk at 48 h post admission.

The Spanish version of the STRONGkids has valid content, in terms of the relevance, clarity and simplicity of its items, to determine the risk of undernutrition in the Spanish population. We consider that the items completed by the caregivers and/or family of the child need to be investigated. Until the reproducibility of these items in terms of the agreement between the assessment made by different caregivers is established, this screening tool must be applied when the child is accompanied by the primary caregiver.

The Spanish version of the STAMP doses not have valid content to determine the risk of undernutrition in the Spanish population. In our opinion, the weight and height item needs to be modified, simplifying its operational definition and adapting it to growth standards applied in our region.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Balaguer López E, García-Molina P, Núñez F, Crehuá-Gaudiza E, Montal Navarro MÁ, Pedrón Giner C, et al. Adaptación transcultural al español y validez de contenido de 3 escalas de riesgo nutricional. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;97:12–21.