The editorial process of scientific journals is complex but essential for the dissemination of scientific knowledge. The quality of the process depends on the authors, editors and reviewers, who must have the necessary experience and knowledge to ensure the quality of the published articles. One of the most significant challenges scientific journals face today is the peer review of manuscripts. Editors are responsible for coordinating and overseeing the entire editorial process, from manuscript submission to final publication, and ensuring that articles meet ethical and scientific integrity standards. Editors are also in charge of selecting appropriate reviewers. However, the latter is becoming difficult due to the increasing refusal of expert reviewers to participate in the editorial process. The reasons for it are diverse, but the lack of recognition for review work and reviewer fatigue in the most sought-after reviewers are among the most important. Some of the measures that could be taken to alleviate the problem concern the possibility of professionalizing peer review.

El proceso editorial de las revistas científicas es complejo pero esencial para la diseminación del conocimiento científico. La calidad del proceso reside en los autores, editores y revisores, quienes deben tener la responsabilidad, experiencia y el conocimiento necesario para garantizar la calidad de los artículos publicados. Uno de los retos más importantes que enfrentan las revistas científicas en la actualidad es la revisión por pares de los manuscritos. Los editores son responsables de coordinar y supervisar todo el proceso editorial, desde la recepción del manuscrito hasta la publicación final, y asegurar que los artículos cumplan con los estándares éticos y de integridad científica. Además, los editores tienen la responsabilidad de seleccionar correctamente a los revisores. Sin embargo, esta última tarea se está volviendo complicada debido al rechazo por parte de revisores expertos a participar en el proceso editorial. Los motivos son diversos, pero destacan la falta de reconocimiento del trabajo de revisor y el desgaste de los revisores más solicitados. Algunas de las medidas que se podrían tomar para paliar el problema se relacionan con la profesionalización de la revisión por pares.

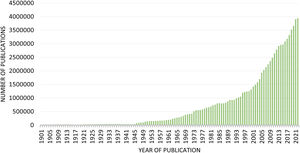

The editorial process of scientific journals is enormously complex. The publication of research findings in scientific journals is the main vehicle for the dissemination of knowledge, and therefore must be done correctly. Just as the introduction of pharmaceuticals in clinical practice requires studies conducted with the most rigorous and thorough methodology possible, the introduction of any new knowledge in the scientific community should require the application of equally stringent quality standards. Deciding what to publish or leave unpublished is a task that places enormous responsibility on the editors of scientific journals, who must screen submitted works as objectively as possible based on criteria related to aspects like methodological quality, the relevance to the journal’s readership, novelty of the content, or the comprehensibility and applicability of the findings. This task has grown increasingly challenging, to a large extent due to the increase in the volume of manuscripts submitted for publication, which can be inferred based on the exponential increase in the number of scientific publications since the 1990s (Fig. 1). It is reasonable to assume that if the number of articles has quadrupled since 1997, the workload of the editors and reviewers of scientific journals must have increased in proportion, overloading editorial management systems.

Broadly speaking, it could be said that the quality of the editorial process depends on the individuals involved in it, chiefly academic authors or researchers, editors and reviewers. It is essential for all these actors to have the necessary experience and knowledge to guarantee the quality of published articles. However, there are additional factors at play, such as whether submission systems are expeditious and user-friendly, there is effective communication between authors and journals, articles are processed for publication within a reasonable timeframe or the format of the final publication is adequate, among others. The quality of published articles stems in large part from the professionality and knowledge of all involved parties.

The editorial process of scientific journals has been subject to criticism on several accounts. In this special article, we focus on one of the most important challenges facing scientific journals: the review of manuscripts by peers. Peer reviewing is a key component of the editorial process the purpose of which is to guarantee that published articles meet the necessary quality standards for the correct dissemination of knowledge.1 However, this process has also come under scrutiny in recent years due to the lack of transparency or potential lack of professionalism of reviewers, among others.2

Who are the editors of scientific journals?Editors are usually selected by the management of the journal and are generally renowned professionals and researchers in the corresponding field. At minimum, this entails that they are thoroughly knowledgeable of a specific research field related to the subject of the journal (such as neonatology, childhood respiratory diseases, neonatal diseases, etc.) who may practice or be an academic or professor in the field. They also have to have published in the past, and therefore know the editorial process of scientific journals, if only from the perspective of the author.

The editors of scientific journals are responsible for coordinating and supervising the entire editorial process, from the reception of manuscripts to their final publication.3 Their duties usually include selecting the articles to be published, reviewing and editing the manuscripts, coordinating the peer review, selecting the reviewers and make the final decisions regarding publication.4 In addition, they are responsible for ensuring that papers meet ethical and scientific integrity standards. In short, editors ensure the correct functioning of the editorial process. It is important to consider that the role of editor in a scientific journal is usually not remunerated and that it is a time-consuming activity. Therefore, the manuscripts editors receive should be submitted appropriately, be easy to understand (in a single reading) and be written in an adequate style. Any manuscripts that do not have these characteristics is likely to be rejected.

The role of authors and editors in the editorial processThe authors of scientific content also have responsibilities in the editorial process and must be aware of a series of issues before submitting a manuscript to a journal. In fact, authors are the first parties on whom the quality and integrity of published data and results depend, and they have the obligation to communicate original findings that are truly relevant, avoiding “salami publishing” (splitting the results of a single study to publish in different papers as if they were results from multiple studies, as opposed to producing a single paper), or very small samples for diseases or conditions that are either well known or frequent, among other potential problematic practices. Authors must adhere to ethical and scientific integrity standards. In addition, manuscripts should be submitted for publication in a way that can be easily conveyed to the audience, using an appropriate scientific style and in a format that presents the results clearly and concisely. It is important to keep in mind that the editorial process in general, and in a scientific journal in particular, can easily be overwhelmed if submitted manuscripts do not meet minimum quality standards. A careful review by every author prior to submission to identify and correct any errors can contribute to improving the quality and efficiency of the editorial process. However, it is also worth noting that some journals require authors to format the manuscript according to very specific style guidelines, which may take a considerable amount of time, which is particularly onerous if the manuscript ends up being rejected. To improve the efficiency of the editorial process, some journals are considering doing away with specific formatting requirements. This would not only save time for authors, but also streamline the editorial process.5

However, it is also important to realize that researchers are under enormous pressure to publish, especially in highly competitive academic and scientific environments.6 This pressure can lead some researchers to submit manuscripts that are not fully developed or that do not contain novel or relevant information. This can hinder the editorial process of scientific journals, as the increasing number of manuscripts submitted to any journal increases the workload of its editors. These are the cases in which the editor should exert its actual professional role, acting as gatekeeper and filtering out this type of articles, even if some are submitted for peer review for a more thorough evaluation.

In this regard, editors have different approaches as to how many manuscripts they send out for peer review. On one hand, there are editors that send out many manuscripts, which may enhance the rigour and quality of the editorial process. On the other, there are some who send out few manuscripts for review, which may make the editorial process quicker but also may result in overlooking and rejecting articles that could have been good after making some improvements. The optimal approach is probably somewhere in between. It may be preferable to be a stringent rather than a lax editor, for ultimately the former attitude will promote the publication of only the best articles, facilitate the work of reviewers and avoid fatigue.

The peer review processWhile the authors and editors of scientific journals play key roles in the editorial process, peer reviewers are equally important. We must take into account that the current system of scientific publishing is based on the peer review process, an essential step aimed at ensuring the quality of the scientific output.7 Reviewers must be experts on the subject of the papers they review, provide constructive feedback to improve manuscripts, avoid any conflicts of interest and adhere to journal deadlines, among other duties.8

Although the term “peer review” is not very specific, the most widely used definition may be the one proposed by Olson in 19909: “the assessment by experts of material submitted for publication”. According to this definition, the manuscript is to be reviewed by professionals with sufficient training and expertise to provide constructive criticism of the submitted material and to enhance its strengths. It is worth noting that, at present, the latter aspect tends to be neglected, despite its importance.

In recent years, the peer review process has been widely criticised for several reasons. One of the challenges at hand is the delay in the publication of manuscripts, which in turn is intimately associated with the considerable difficulty in finding reviewers willing to review scientific papers. The reasons that scientists and scholars refuse to review manuscripts are manifold.10 On one hand, the time spent in peer reviewing may be perceived as an added burden in a context that is already stressful and competitive. In addition, reviewer fatigue, especially in highly qualified reviewers, contributes to the difficulty in finding professionals willing to collaborate regularly in the peer review process. This fatigue stems from the substantial volume of requests received by professionals to perform peer reviews. A recent study found that 30% of academic chemists reviewed between 16 and 25 papers a year, and 6% reviewed 50 or more.11 Another reason why professionals may refuse to review manuscripts is the lack of recognition or rewards for the review work. At present, in most cases, peer review is completely anonymous, and the work of reviewers is not officially recognised, nor is it paid, so there is little incentive to engage in this task.12 This is particularly problematic in the case of open-access journals. In many of these journals, authors have to pay fees to publish, but this income reaches other actors (such as editors), but not reviewers, who continue to receive no remuneration for their involvement.

The fatigue of reviewers associated with the aforementioned factors is one of the current challenges facing scientific journals and can have repercussions for the entire scientific community due to delays in the editorial process and therefore in the dissemination of scientific knowledge. Another important consequence must be noted: since expert reviewers cannot be found, editors have been forced to resort to less experienced reviewers. This poses a problem insofar as reviewers without the necessary expertise may agree to review a manuscript. In such cases, two things may happen: first, the publication of scientific articles with fundamental methodological flaws that reviewers failed to identify, and, secondly, the rejection of good scientific articles because reviewers become overly critical in the attempt to be thorough in their review of the content. The skill to differentiate essential from incidental changes develops with experience.

These issues notwithstanding, peer review continues to be the gold standard for the evaluation of scientific papers.13,14 Still, it is a system that requires improvements and solutions to the problems discussed above, which probably entail incentivization and acknowledgment of the work of reviewers and to invest in their training. In other words, the professionalization of reviewers. Some initiatives along these lines have been implemented in the past few years, such as the recognition of reviewers through Publons or the Web of Science or the submission of certificates for performed reviews. These may be worthy accomplishments to include in a curriculum vitae. However, we ought to underscore that for the time being, academic and research institutions do not recognise peer review as a merit.

Thus, scientific journals could develop and implement various strategies to help professionalize peer review. In this context, professionalization refers to the improvement of knowledge and training to engage in peer reviewing and some form of reward or compensation for the work, rather than making it into a profession. One interest idea is the development of “peer reviewer academies” offering training that journals could deliver in the form of pre-conference courses or even online. One of the main problems is that researchers are not trained in peer reviewing,12 so this type of initiative could be a helpful solution.3 In-person courses, if taught by members of editorial boards, could offer substantial value and train a growing body of reviewers (chiefly young professionals, such as medical residents or doctoral and postdoctoral researchers), instilling the desire and interest to review articles and providing detailed insight on the internal operations of scientific journals. On the other hand, in pursuit of the same goal, scientific journals could facilitate the work of reviewers through the development and implementation of a standardised format for peer reviewing, as we proposed recently.15 In some cases, editorial boards may also give small rewards from time to time to reviewers who produce high-quality work. The editorial board of the journal may, for instance, extend the offer to the reviewer to write an editorial in relation to the article, thus rewarding their work in some form. In some open-access journals, reviewers may be offered discounts in the publication fees for their own articles in the same journal. There is evidence that such rewards are effective incentives for reviewers.10

While we have indeed reached a point at which the professionalization of peer reviewing is important and necessary, this should not be the sole reason to make high-quality reviews. A commitment to science and the scientific community should be the main motivation of peer reviewing. Being a “good citizen” of the scientific community involves not only publishing, but also making a contribution through the review of manuscripts so that other researchers can also publish and disseminate their findings.10,11

Another challenge for scientific journals: research misconductAnother of the main criticisms against the peer review process is the lack of adequate detection of practices considered research misconduct in scientific papers. For example, there is evidence that peer review cannot effectively identify or prevent the publication of manuscripts containing manipulated or duplicated images.16 Since the “publish or perish” system can make or break a professional career,6 either academic or clinical, there is a risk that researchers will engage in unethical practices. Research misconduct comprehends numerous practices, such as guest or ghost authorship, salami publication, falsification or fabrication of data or plagiarism, among others,17 and each of them requires specific strategies to prevent and detect it. While these forms of misconduct are what are known as the “classic” forms, as the field of scientific publishing evolves, new forms of research misconduct develop. A recent example is the proliferation of what are known as “paper mills”. In scientific publishing, this term refers to for-profit organizations that mass-produce fraudulent papers to sell to researchers, students or academics.18 Other emerging forms of research misconduct are the potential creation and recommendation of fictitious reviewers or the abuse of known reviewers.19

In this context, new approaches have emerged for the review of scientific manuscripts, such as open peer review and post-publication peer review, in an attempt to increase the transparency of peer review.2,20 In addition, editorial teams need to be increasingly vigilant and should invest resources to discourage or detect such unethical practices, although in some instances this proves difficult, and it has become evident that the peer review process alone does not suffice to prevent the publication of fraudulent material.16 Publishing houses and scientific journals have adopted new editorial rules and policies to confront this problem or at least make it harder for authors who attempt to engage in these practices. One of the rules that is already being applied is limiting the number of authors allowed, to ensure that those who are featured meet the authorship criteria. Some journals do not allow any changes to the list of authors to avoid articles from paper mills, as changing the authors once the manuscript is accepted is one of their common tactics.21 When it comes to reviewers, possible strategies include avoiding the suggestion of reviewers (since reviewers suggested by authors generally tend to provide more favourable recommendations of the articles they review22) or excluding reviewers with non-institutional email addresses, to prevent the use of fake reviewers.21 Since the early 2000s, most scientific journals have been using software to detect plagiarism (iThenticate, Turnitin).23 Other software solutions are currently being studied, for instance, software for the detection of duplicated images,24 although their use is not yet widespread. Potential applications of emerging technologies to detect problems in the manuscripts submitted to journals are also being explored. For example, artificial intelligence could help editors and reviewers identify errors or abnormalities in the submitted data or the statistical analysis.

However, other tricks and subterfuges are not as easy to detect or prevent, such as the use of artificial intelligence software to write articles, the submission of salami publications and even less problems involving the falsification or alteration of research data and results. While policies and strategies implemented by journals are an important step toward safeguarding scientific integrity, these measures must be complemented by actions taken by the institutions that authors are affiliated to, funding agencies and research integrity offices.25,26

ConclusionPeer review is a key element contributing to the quality of the final product of scientific journals. However, there are various challenges that must be addressed to guarantee the transparency and rigour of the editorial process. One of them, which is currently growing in importance, is reviewer fatigue and scarcity. The peer review process needs improvements and solutions that will probably entail creating incentives, recognising and possibly remunerate in some form the work of reviewers, as well as investing in their training. Scientific journals could develop and implement various strategies to promote the professionalization of peer review, such as the foundation of a reviewer academy offering courses on peer reviewing. There are multiple reasons why peer review could be considered valuable for scientific knowledge and should continue to be used, although there is also ample opportunity for improvement.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.