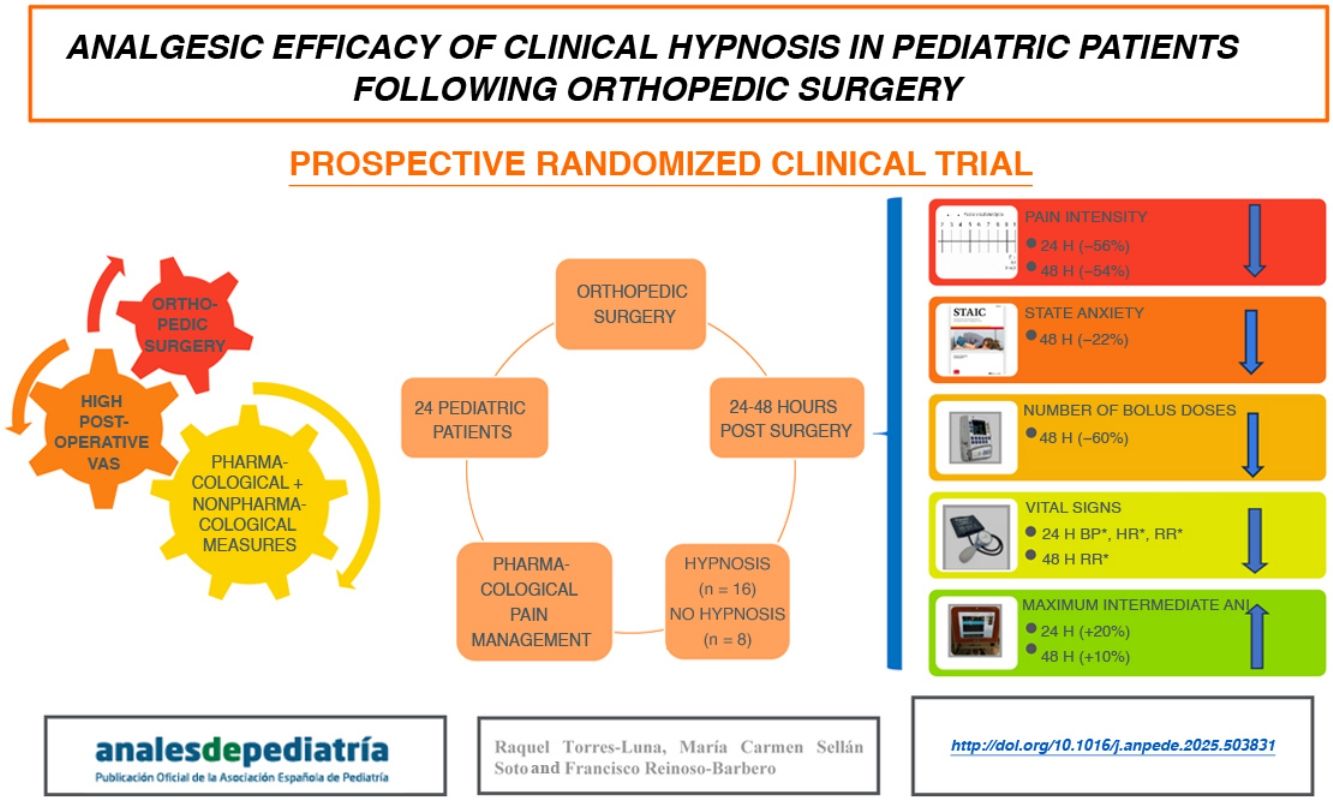

Clinical hypnosis is effective for pain management in adults, but there is little evidence of its use in the pediatric population.

Materials and MethodsWe conducted a randomized clinical trial on pediatric patients (aged 7–19 years) that had undergone major orthopedic surgery, allocated to one of two groups: the experimental hypnosis group (HG), which received two sessions of clinical hypnosis, or the control group (CG), which had two non-hypnosis visits. The variables analyzed were pain (Visual Analog Scale [VAS]), use of analgesic drugs, anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children [STAIC]), parasympathetic activation (Analgesia Nociception Index [ANI] monitor) and vital signs such as heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP). We used the Student t test and the χ2 test for the statistical analysis.

ResultsOf the 24 patients in the sample, 16 were assigned to the HG and 8 to the CG. In the HG, we observed a significant reduction in VAS scores at 24 h (P = .0001) and 48 h (P = .0004) post surgery. Additionally, HG patients required fewer rescue doses of analgesic agents (P = .025) and had lower state-anxiety scale scores in the STAIC (P = .046). The ANI values increased significantly at 24 h (P = .0001) and 48 h (P = .007). The HR, SBP and DBP values decreased at 24 h (P < .05), and the RR at 24 and 48 h (P < .05).

ConclusionClinical hypnosis is an effective nonpharmacological intervention for reducing postoperative pain and anxiety in children, and it is associated with an increase in parasympathetic tone.

La hipnosis terapéutica es un eficaz tratamiento del dolor en adultos, pero en población pediátrica no ha sido ampliamente estudiada.

Material y métodosSe realizó un ensayo clínico aleatorizado en los pacientes pediátricos (7–19 años) sometidos a cirugía ortopédica mayor, en 2 grupos: el grupo experimental (GH) recibió 2 sesiones de hipnosis clínica, mientras que el grupo control (GC) tuvo 2 visitas sin hipnosis. Se evaluaron: dolor (escala visual analógica [EVA]), consumo analgésico, ansiedad (State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children [STAIC]), activación parasimpática con el monitor de Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI) y constantes vitales como frecuencia cardíaca (FC), frecuencia respiratoria (FR) y tensión arterial sistólica y diastólica (TAS y TAD). Se utilizaron las pruebas de la t de Student y la de Chi-cuadrado para el análisis estadístico.

ResultadosDe los 24 pacientes estudiados, 16 fueron asignados al GH y 8 al GC. En el GH se constató un descenso significativo en la EVA a las 24 (P = ,0001) y 48 horas (P = ,004) postoperatorias. También en el GH hubo una reducción los bolos de rescate (P = ,025) y en el valor de STAIC-Estado (P = ,046). Además, en el GH se registró un aumento del ANI a las 24 (P = ,0001) y 48 horas (P = ,007), junto con un descenso de FC, TAS, TAD a las 24 h (P < ,05) y de la FR a las 24 y 48 horas (P < ,05).

ConclusionesLa hipnosis clínica es una intervención no farmacológica eficaz para reducir el dolor y la ansiedad postoperatoria en niños, asociándose a un aumento del tono parasimpático.

Numerous factors play a role in the approach to pain management, and an increasing number of studies support the importance of addressing emotional, psychological and social factors,1 in addition to physiological ones, which may be more related to nociception. Nociception is the process of detecting and transmitting information about potential damage (and is usually modulated with pharmacological treatment), while pain is a subjective experience resulting from how the brain interprets these signals,2 the management of which has to be supplemented with nonpharmacological measures to modulate the psychological factors at play in order to achieve better results.3

Hypnosis is one of the available nonpharmacological analgesia methods, and, while in some instances it has been associated with nonmedical events, it is a technique with a long trajectory. The clearest references to the use of suggestion techniques in antiquity have been attributed to the Egyptians, circa 1500 BC, and specifically to a valuable document in the possession of the University of Leipzig: the Ebers Papyrus.4 But it was not until the 19th or 20th century that hints of the use of analgesic techniques based on suggestion in surgical or painful procedures start to appear in the medical literature.5,6

This marked the beginning of the use of clinical hypnosis for management of acute pain, in which we ought to highlight studies in the management of childbirth pain7 and painful oncological procedures, such as lumbar puncture and bone marrow biopsy,8,9 as well as chronic pain in the context of severe chronic disease10 or palliative care,10,11 with the approach proving effective for both types of pain.

The effect of hypnosis depends on the suggestibility of the subject and is the result of complex cerebral interactions involving the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingular cortex and the limbic system. During hypnosis, there is an increase in functional connectivity and a decrease in the activity of the default mode network, enhancing the responsiveness to suggestion.12–14 The analgesic effects emerge from the activity of the descending pain pathways and the release of endorphins.15

Childhood and adolescence are stages characterized by significant neuroplasticity, and the child’s brain is particularly susceptible to suggestion and nonpharmacological analgesia methods due to its considerable capacity for imagination and symbolism,16,17 allowing the child to be easily transported to imaginary worlds, so, a priori, the degree of suggestibility in children should be high.18

In major orthopedic surgery, the level of pain in the immediate and intermediate postoperative periods ranges from moderate to severe. In this context, multimodal analgesia is common, usually combining opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to achieve adequate pain control.3,19 Many of these patients experience anticipatory anxiety,20 especially those who have been operated before.

The use of hypnosis for management of postoperative pain in pediatric patients has been found to produce subtle changes in pain and the use of analgesic drugs.21 More rigorous studies are required to assess its impact on pain, anxiety and physiological wellbeing using parasympathetic activity as an indicator.22

We conducted a study with the hypothesis that the use of hypnosis and self-hypnosis in the postoperative period would reduce the severity of pain and anxiety, vital signs values and the demand for analgesic drugs of pediatric patients that had undergone major orthopedic surgery.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a prospective randomized clinical trial in a tertiary care children’s hospital in pediatric patients scheduled for major orthopedic surgery in adherence to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital on July 18, 2020 (code 5499). We obtained informed consent from the parents and pediatric patients in Spanish.

Study population and sample size calculationThe study universe consisted of the 100 patients a year who underwent major orthopedic surgery and needed pain management with a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. Based on similar studies that detected a difference of 24% in parasympathetic activity,22 we estimated that the minimum necessary sample was of 24 patients for a level of confidence of 95% and a precision of 15%. We included patients who underwent major orthopedic surgery and left the operating theater with a PCA pump for intravenous or epidural delivery of opioids and other analgesic drugs. We ensured that the patients understood how the pump worked and their capacity to use it. We excluded patients with psychomotor retardation, mental disorders, a suggestibility score of less than 30 or who did not speak Spanish.

Random allocationWe obtained a simple random sample using the Excel software, with random allocation of patients to either the experimental hypnosis group (HG) or the control group (CG).

Instruments- -

Visual analogue scale (VAS)23: self-report instrument consisting of a 10 cm line to indicate the intensity of pain, scored on a scale from 0 to 100.

- -

Suggestibility inventory (SI): scale consisting of 22 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4 points) with a possible total score ranging from 0 to 88 points (greater scores indicate greater suggestibility). The original study found a good test-retest reliability (0.70) and an acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α, 0.79).24

- -

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC)25: it includes two 20-item self-report scales, with items rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 3 points for a maximum possible score of 60 points per scale (higher scores indicate greater anxiety).

- -

Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI)22,26: noninvasive approach for the assessment of nociception and its management based on the sympathovagal balance, consisting of the analysis of an electrocardiogram performed with three electrodes to measure the parasympathetic tone. The score ranges from 0 to 100 (lower values indicate greater sympathetic activity, higher values, less activity). We calculated the mean values for two time intervals during monitoring: immediate (2 min) and intermediate (4 min). Values between 50 and 70 indicate comfort relative to baseline.26,27

The independent variable was the use of clinical hypnosis in the postoperative period (yes/no) and the dependent variables were: pain level assessed with the VAS, opioid consumption (number of self-administered bolus doses), state-trait anxiety assessed with the STAIC and physiological variables (heart rate [HR], respiratory rate (RR), systolic blood pressure [SBP] and diastolic blood pressure [DBP]), and the analgesia nociception index in the intermediate period (“intermediate ANI”).

Study protocolPatients scheduled for major orthopedic surgery and who were eligible for participation based on the postoperative pain treatment protocol with a PCA pump were selected. The principal investigator recruited patients during preoperative visits for pre-anesthesia assessment or acute pain management, and participation was confirmed on the day of the surgical intervention. At that time, the parents/legal guardians and child signed the informed consent form and the SI and STAIC were administered prior to any psychological intervention. In both groups, we collected data on the variables of interest at 24 and 48 h post surgery (before and after the hypnosis intervention in the HG and at the same time points in the CG).

The principal investigator, who had specialized training and a certificate in clinical hypnosis accredited by the board of psychology, had degrees in nursing and psychology and was in charge of delivering the intervention in every patient. The hypnosis protocol, which was the same in every patient, comprehended a series of steps carried out at 24 and 48 h post surgery in the experimental group only5: pre-induction phase (explaining the process and objectives), induction stage (implementation of hypnosis techniques: eye fixation and mountain hike visualization script), delivery of specific suggestions (modification of cognitive, physiological or motor responses: classic suggestion strategies and analgesia and relaxation metaphors) and post-hypnotic phase (confirmation and generalization of what was learned: post-hypnotic suggestions and education on self-hypnosis).

Statistical analysisTo analyze sociodemographic characteristics, social and health care-related variables and SI results, we calculated means, standard deviations and percentages. We compared study variables in the experimental and control groups to assess homogeneity, using the Student t test for quantitative data and the χ2 test for qualitative data. We compared the measured values in the HG and CG before and after the intervention (clinical hypnosis) using the Student t test. All variables were coded and analysed with the statistical software included in Excel and we set the statistical significance threshold at 0.05.

ResultsThe study was carried out between June 2021 and July 2022. The total sample comprised 24 pediatric patients aged 7–19 years randomly assigned to the HG (16 patients) or CG (8 patients).

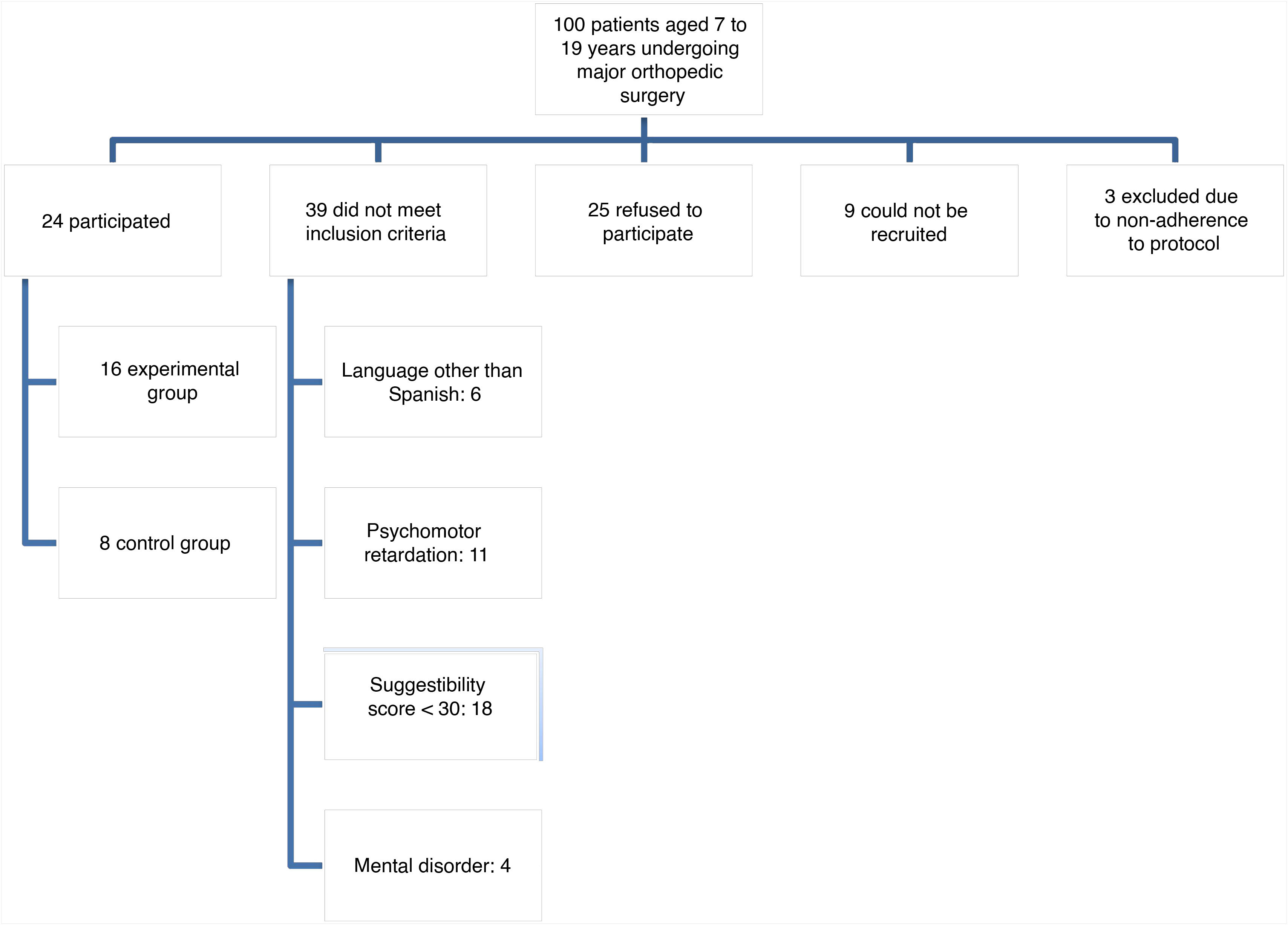

Fig. 1 shows the patient selection and recruitment process. Of the 100 patients that underwent major orthopedic surgery in our hospital during the study period, 24 accepted to participate, 29 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 25 refused to participate, 9 could not be recruited (because they underwent surgery during the weekend) and 3 did not adhere to the study protocol.

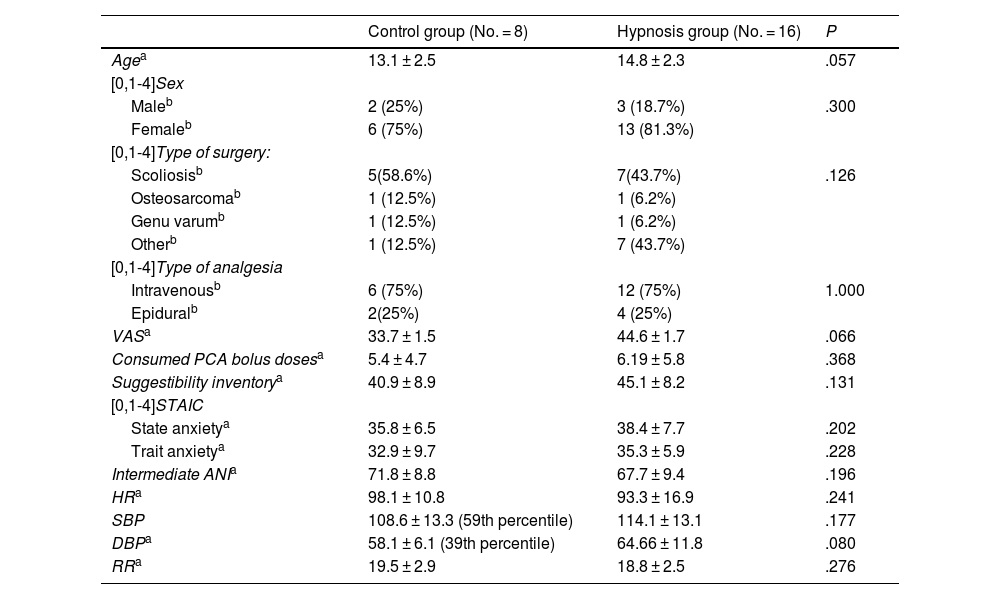

The sample was divided in two groups, described in Table 1. We did not find significant differences between the groups.

Demographic characteristics of the two groups under study: control group and hypnosis group.

| Control group (No. = 8) | Hypnosis group (No. = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 13.1 ± 2.5 | 14.8 ± 2.3 | .057 |

| [0,1-4]Sex | |||

| Maleb | 2 (25%) | 3 (18.7%) | .300 |

| Femaleb | 6 (75%) | 13 (81.3%) | |

| [0,1-4]Type of surgery: | |||

| Scoliosisb | 5(58.6%) | 7(43.7%) | .126 |

| Osteosarcomab | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (6.2%) | |

| Genu varumb | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (6.2%) | |

| Otherb | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (43.7%) | |

| [0,1-4]Type of analgesia | |||

| Intravenousb | 6 (75%) | 12 (75%) | 1.000 |

| Epiduralb | 2(25%) | 4 (25%) | |

| VASa | 33.7 ± 1.5 | 44.6 ± 1.7 | .066 |

| Consumed PCA bolus dosesa | 5.4 ± 4.7 | 6.19 ± 5.8 | .368 |

| Suggestibility inventorya | 40.9 ± 8.9 | 45.1 ± 8.2 | .131 |

| [0,1-4]STAIC | |||

| State anxietya | 35.8 ± 6.5 | 38.4 ± 7.7 | .202 |

| Trait anxietya | 32.9 ± 9.7 | 35.3 ± 5.9 | .228 |

| Intermediate ANIa | 71.8 ± 8.8 | 67.7 ± 9.4 | .196 |

| HRa | 98.1 ± 10.8 | 93.3 ± 16.9 | .241 |

| SBP | 108.6 ± 13.3 (59th percentile) | 114.1 ± 13.1 | .177 |

| DBPa | 58.1 ± 6.1 (39th percentile) | 64.66 ± 11.8 | .080 |

| RRa | 19.5 ± 2.9 | 18.8 ± 2.5 | .276 |

Abbreviations: HR, heart rate; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STAIC, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; VAS, visual analogue scale.

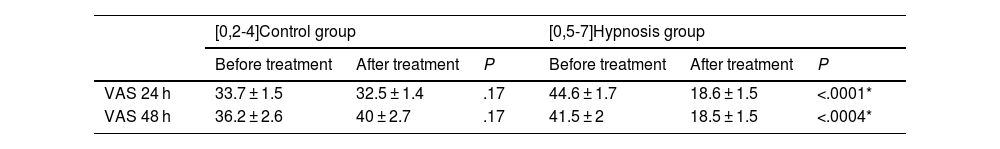

Table 2 shows how the values in the VAS decreased significantly after the study intervention only in the hypnosis group compared to the control group at both 24 h (P = .0001) and 48 h (P = .0004) post surgery.

Differences in visual analogue scale values before and after treatment at 24 and 48 h post surgery in the control group (no hypnosis) and experimental group (hypnosis).

| [0,2-4]Control group | [0,5-7]Hypnosis group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | P | Before treatment | After treatment | P | |

| VAS 24 h | 33.7 ± 1.5 | 32.5 ± 1.4 | .17 | 44.6 ± 1.7 | 18.6 ± 1.5 | <.0001* |

| VAS 48 h | 36.2 ± 2.6 | 40 ± 2.7 | .17 | 41.5 ± 2 | 18.5 ± 1.5 | <.0004* |

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analogue scale.

Expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

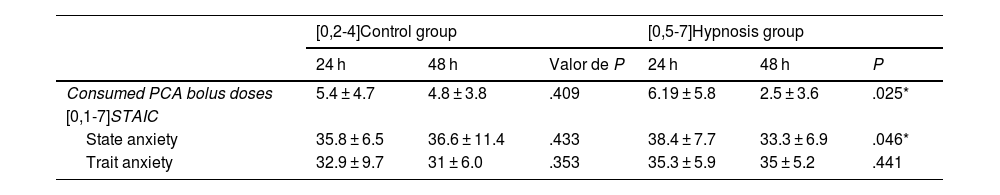

Table 3 shows the differences in the consumption of self-administered analgesic bolus doses and the level of anxiety observed in patients at 24 and 48 h post surgery. We found a significant reduction in the hypnosis group (HG) in the need of analgesic bolus (P = .025) and state-anxiety measured with the STAIC (P = .046).

Differences in the number of self-administered analgesic bolus doses and the trait and state anxiety values at 24 and 48 h in the control (no hypnosis) and hypnosis groups.

| [0,2-4]Control group | [0,5-7]Hypnosis group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | Valor de P | 24 h | 48 h | P | |

| Consumed PCA bolus doses | 5.4 ± 4.7 | 4.8 ± 3.8 | .409 | 6.19 ± 5.8 | 2.5 ± 3.6 | .025* |

| [0,1-7]STAIC | ||||||

| State anxiety | 35.8 ± 6.5 | 36.6 ± 11.4 | .433 | 38.4 ± 7.7 | 33.3 ± 6.9 | .046* |

| Trait anxiety | 32.9 ± 9.7 | 31 ± 6.0 | .353 | 35.3 ± 5.9 | 35 ± 5.2 | .441 |

Abbreviation: STAIC, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children.

Values expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

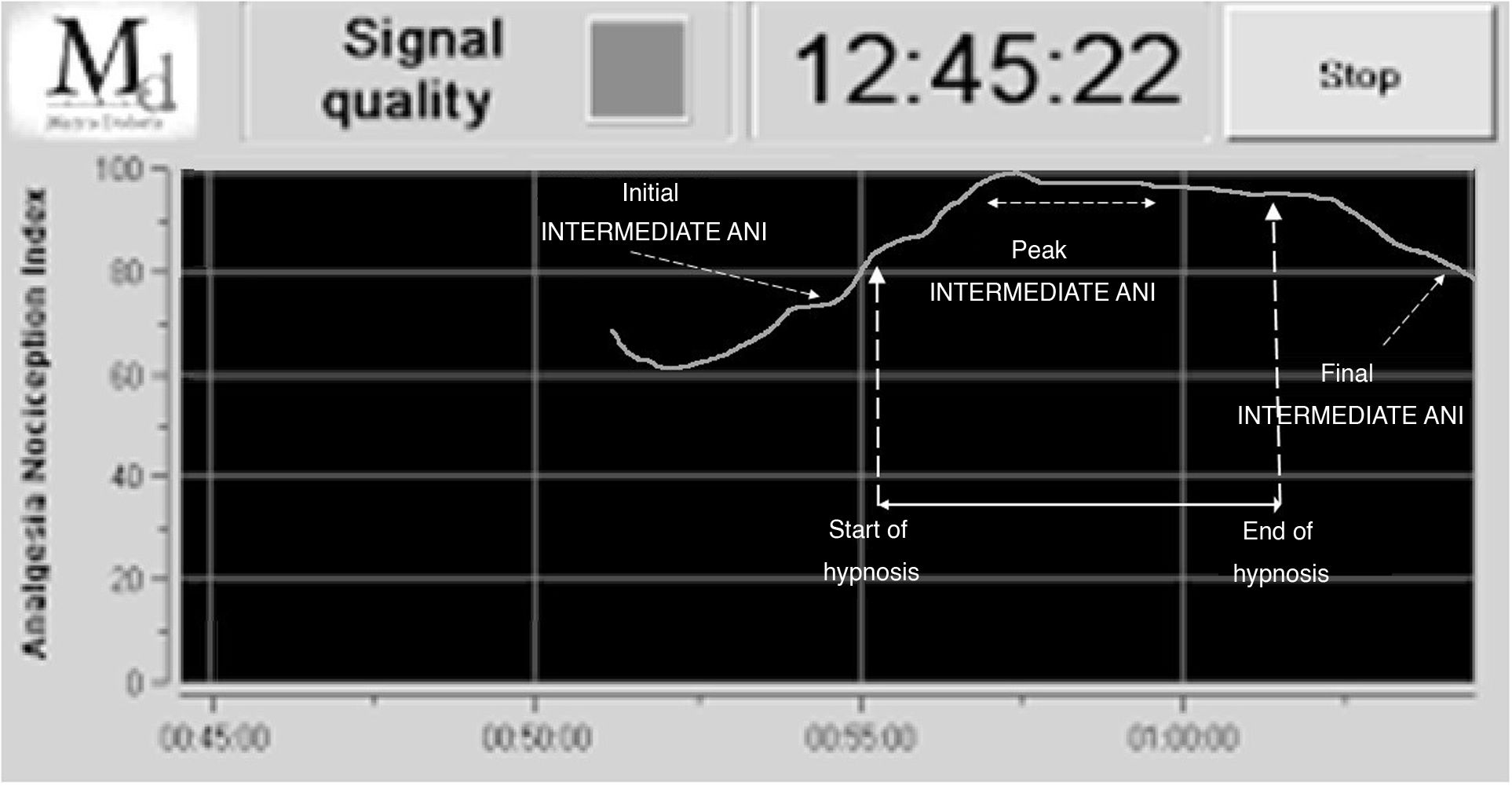

Fig. 2 presents a screenshot of the ANI monitor in a typical case in the hypnosis group, showing the recording of the initial, maximum and final intermediate ANI values.

The figure shows how in the HG, ANI values reached the maximum during the delivery of suggestions and remained at that level for several minutes, with this peak spanning for a significant percentage of the total duration of the hypnosis sequence.

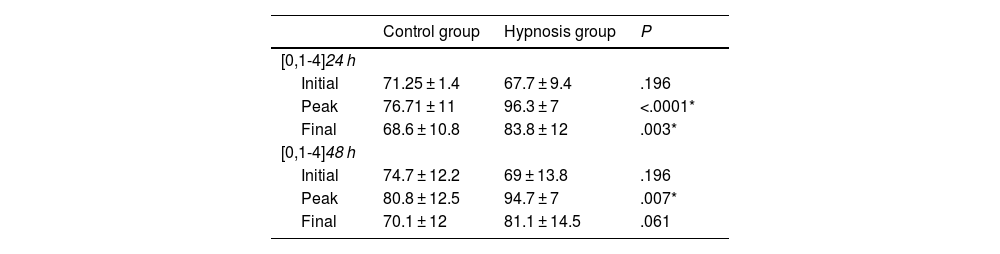

Table 4 presents the ANI values obtained at three points of the hypnosis process, with a statistically significant increase in the maximum intermediate interval ANI values both at 24 h (P = .0001) and 48 h (P = .007) post surgery and final ANI values at 24 h (P = .003).

Comparison of intermediate interval ANI values before, during and after the treatment in the control group (no hypnosis) and experimental group (hypnosis) at 24 and 48 h post surgery.

| Control group | Hypnosis group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1-4]24 h | |||

| Initial | 71.25 ± 1.4 | 67.7 ± 9.4 | .196 |

| Peak | 76.71 ± 11 | 96.3 ± 7 | <.0001* |

| Final | 68.6 ± 10.8 | 83.8 ± 12 | .003* |

| [0,1-4]48 h | |||

| Initial | 74.7 ± 12.2 | 69 ± 13.8 | .196 |

| Peak | 80.8 ± 12.5 | 94.7 ± 7 | .007* |

| Final | 70.1 ± 12 | 81.1 ± 14.5 | .061 |

Abbreviation: ANI, Analgesia Nociception Index.

Values expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

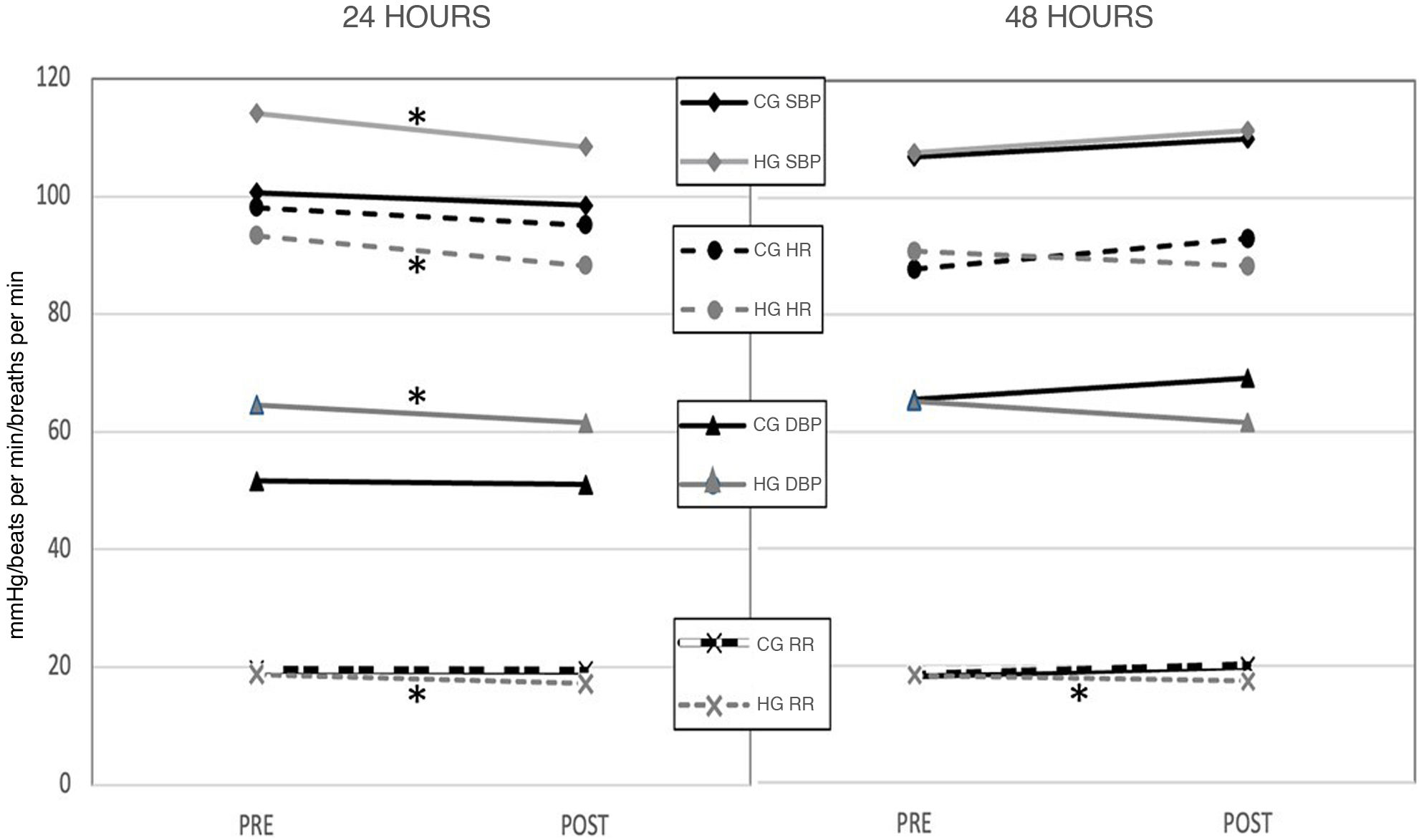

Last of all, Fig. 3 shows the variation in the other physiological variables (HR, SBP, DBP and RR), with a significant decrease in all at 24 h and a significant decrease in RR also at 48 h post surgery (24 h: HR P = .014; SBP P = .01; DBP P = .047 and RR P = .007; 48 h: P = .047).

Measurement of vital signs: systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR) and respiratory rate (RR) values before and after the treatment in the control group (CG) and the hypnosis group (HG) at 24 and 48 post surgery. The mean value is shown. * Statistical significance: P < .05.

In our study, we made a comparative assessment of the effectiveness of clinical hypnosis in pediatric patients that had undergone major orthopedic surgery, evaluating pain and anxiety measures and physiological responses in the immediate postoperative period. While previous studies on hypnosis for pain management in adults have yielded promising results,28,29 there is a recognized need for more rigorous research in this field, especially in the pediatric population.

In adults, the beneficial effect of hypnosis is reflected in a reduction in both preoperative anxiety and opioid consumption.30 In the pediatric population, although the evidence is limited, improvements in acute procedural pain, heart rate and patient cooperation have been reported.31,32 Thus, our study offers relevant information considering that we did not find any significant data in the current literature on the effects of hypnosis in pediatric patients in this particular field.

In the HG, the intensity of pain measured with the VAS decreased significantly after the hypnosis intervention, from 44.6 to 18.6 on day 1 and from 41.5 to 18.5 on day 2, while values remained stable in the CG. When we compared the number of opioid bolus doses self-administered with the PCA pump in the first 24 h post surgery (before hypnosis) and between 24 and 48 h (when one session of hypnosis had been delivered), we found a significant decrease in the HG (P = .02), contrary to the CG, in which consumption did not change (P = .40). The change in the HG could be related to a decrease in the anxiety experienced by these patients, reflected in a decrease in the STAIC scores, with a 5-point decrease in the state anxiety scale compared to baseline in the HG while the values remained unchanged in the CG. Future studies could assess the effects of hypnosis over time using different time intervals (8, 12 h…).

The decrease in the required number of bolus doses is particularly significant if we take into account the current multimodal analgesia approach,33 based on the combination of first- and second-tier analgesics and adjuvants, which in itself achieves a decrease in opioid consumption.

These findings indicate that hypnosis can be used to modulate the perception of physiological sensations in pediatric patients and self-control. With regard to pain, the change is substantial at the end of the session, with patients reporting significantly lower pain levels through the VAS. When it came to anxiety, we observed a remarkable change in state anxiety after two hypnosis sessions, without changes in trait anxiety, as would be expected given the stable nature of a personal trait. In future research, it would be interesting to assess whether the changes in these variables persist beyond 48 h post surgery.

The effect of hypnosis on the autonomic nervous system is reflected in the recent review by Fernández et al.34 and was demonstrated in our study through the changes in vital signs (HR, SBP-DBP and RR) following performance of hypnosis, especially at 24 h post surgery, when we observed a significant decrease in all, which indicates a decrease in sympathetic activity throughout the hypnosis process that was sustained at least for a few minutes after the session.

In relation to this, one of the most remarkable effects of hypnosis observed in our study that has been previously described is the modulation of parasympathetic activity,35 similar to the results reported by Boselli et al.,22 with ANI levels as high as 100 during the “suggestion delivery” phase, with significant mean values of 96.35 at 24 h and 94.77 at 48 h. These high mean values may reflect the complete elimination of nociception, comparable to the effect obtained by opioid administration,36 which would correspond to total absence of pain in the patient for at least the duration of this phase in the hypnotic process.

When we compared ANI values before and after the full hypnosis session we also found an increase in ANI values after the session at the two study time points (24 and 48 h post surgery), with a significant change in mean values from 67.73 to 83.8 at 24 h and from 69 to 81.1 at 48 h in the HG, in the absence of significant change in the CG. The increase in ANI values observed in the HG was positively correlated in the reduction in perceived pain reported by patients after hypnosis through the VAS,31 which decreased substantially in the HG.

In light of these findings, which were consistent with those reported by Boselli et al.,22 ANI monitoring may provide an objective tool for the measurement of the intensity of the hypnotic process,22 as it provides information on the phase of hypnosis the patient is experiencing, which could help optimize psychological treatment. It could help therapists determine which phase of the hypnosis process is most suitable for delivering suggestions, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the intervention.

We established the age range for the study sample (7–19 years) based on the age at which children, from a developmental standpoint, can are capable of understanding and collaborating in the hypnosis process. Prolonged hospitalization can be a stressor, but it ensures continuity in performing the technique and in training children. Education on self-hypnosis can offer children self-regulation strategies and help them feel in control of the situation,16 and can also affect the perception of pain and, as a result, the consumption of medication.

Among the limitations of the study, we ought to highlight the small size of the sample due to difficulties in patient recruitment, as many did not meet the inclusion criteria or refused to participate. One of the strengths is that, despite the small sample size, most of the results were statistically significant. To try to control for participation bias, since parents may have been reluctant to allow their children to be subject to study, we carried out a survey ahead of the study in a group of 50 pediatric patients that had undergone surgery, in which 75% of parents declared that they would not object to their children undergoing hypnosis for management of pain and anxiety. This was consistent with the percentage of selected patients that refused to participate in our study (25%).

On the other hand, hypnotic suggestibility, understood as “an individual’s ability to experience suggested alterations in physiology [somatic changes], sensations, emotions, thoughts, or behavior during hypnosis”37 is a personality trait that is relatively stable over time38 and follows a normal distribution, with approximately 10%–15% of the population displaying low hypnotic suggestibility, 60%–80% displaying moderate responsiveness and 10%–15% exhibiting high hypnotic suggestibility (“hypnotic virtuosos”).39 This is consistent with the percentage of patients excluded from the sample on account of their suggestibility level, assessed by means of the SI, in which a score under 30 was considered a criterion for exclusion, a fact that, combined with difficulties in recruitment, resulted in a small sample size.

Notwithstanding, our findings are promising and allow for optimism, given the significant results obtained for several of the variables studied to assess the effect of hypnosis, as we discussed above.

For the purposes of future research, we would recommend studies in larger samples and with a greater number of hypnosis sessions to assess the long-term effects of the technique on pain and anxiety. Another aspect worth considering is the efficacy of current pharmacological analgesia protocols, as the high values in the VAS, save for after hypnosis, reflect the aggressiveness of major orthopedic surgery. Increasing the number of hypnosis sessions could improve training and achieve longer-lasting effects on pain perception and parasympathetic activity, although our findings suggest that the effects of hypnosis may persist for a while based on the reduction in the number of self-administered bolus doses at 48 h.

In future studies, it would be interesting to analyze the association between hypnosis and variables such as fear or catastrophizing, which may be relevant and potentially modifiable factors in pain perception and for which there is little evidence in the pediatric population. On the other hand, assessing the perceived satisfaction of patients in the HG and their wish to continue using this nonpharmacological analgesia method in future potentially painful events would provide very valuable information about the acceptability of the method in the paediatric population.

ConclusionThe findings of our study suggest that hypnosis may induce nonpharmacological analgesic effects, increase parasympathetic activity and reduce the need for self-administered analgesia in hospitalized pediatric patients, so it is a promising technique for the management of postoperative pain and anxiety.

FundingThis research project did not receive specific financial support from funding agencies in the public, private or not-for-profit sectors.