Acne vulgaris is significantly associated with an increased burden of care and has an important impact on the quality of life (QoL) and self-esteem of affected individuals. We aimed to assess the QoL of adolescents with acne and their families as well as the association of QoL with acne severity, treatment response, duration of acne and localization of lesions.

Material and MethodsThe sample included a total of 100 adolescents with acne vulgaris, 100 healthy controls and their parents. We collected data on sociodemographic characteristics, presentation of acne, duration of acne, treatment history, treatment response, and parental sex. We used the Global Acne Severity scale, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), and the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI).

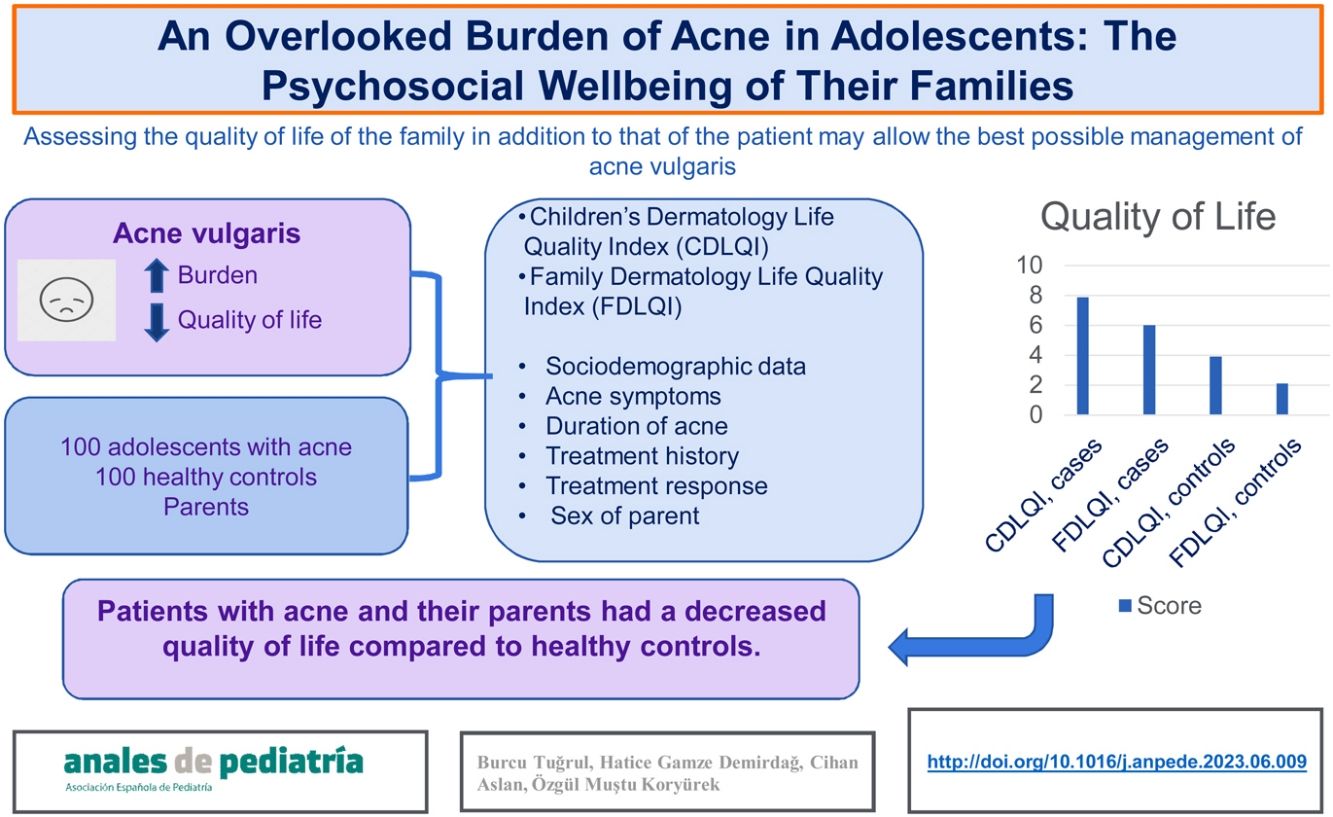

ResultsIn the group of patients with acne, the mean CDLQI score in the patients was 7.89 (SD, 5.43) and the mean FDLQI score in the parents was 6.01 (SD, 6.11). In the control group, the mean CDLQI score in healthy controls was 3.92 (SD, 3.88) and the mean FDLQI score in their family members was 2.12 (SD, 2.91). We found a statistically significant difference between the acne and control groups in CDLQI and FDLQI scores (P < .001). There were also statistically significant differences in the CDLQI score based on the duration of acne and the response to treatment.

ConclusionsPatients with acne and their parents had a decreased QoL compared with healthy controls. Acne was associated with impaired QoL in family members. Assessing QoL in the family in addition to that of the patient may allow an improved management of acne vulgaris.

El acné vulgar se asocia significativamente con un incremento en la carga de cuidados y tiene un impacto importante sobre la calidad de vida (CV) y la autoestima de los afectados. El objetivo de nuestro estudio fue evaluar la CV de los adolescentes con acné y sus familiares así como la asociación entre la calidad de vida y la gravedad del acné, la respuesta al tratamiento, la duración del acné y la región del cuerpo afectada.

Material y MétodosLa muestra incluyó a un total de 100 adolescentes con acné, 100 controles sanos y sus padres. Se utilizaron la escala global de severidad del acné, el índice dermatológico de calidad de vida infantil (CDLQI) y el índice dermatológico de calidad de vida familiar (FDLQI).

ResultadosLa puntuación media de los pacientes en el CDLQI fue de 7,89 (desviación estándar [DE]: 5,43) y la puntuación media de sus familiares en el FDLQI de 6,01 (DE: 6,11). La puntuación media de los controles sanos en el CDLQI fue de 3,92 (DE: 3,88) y la puntuación media de sus familiares en el FDLQI fue de 2,12 (DE: 2,91). Hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los grupos de casos y de control en las puntuaciones en el CDLQI y el FDLQI (p < 0,001). También se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las puntuaciones del CDLQI según la duración del acné y la respuesta al tratamiento.

ConclusionesEn los pacientes con acné y sus familiares la calidad de vida era inferior en comparación con los controles sanos. El acné se asoció a una merma en la CV familiar. La evaluación de la CV de la familia además de la del paciente puede contribuir a mejorar el manejo del acné vulgar.

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit manifesting with papules, pustules, nodules and cysts on the face, chest, and back, and it affects approximately 85% of adolescents.1 It can be a frustrating disease for adolescents, in whom body image is of utmost importance, because it manifests in visible body parts.2 Although it is not a life-threatening condition, it can cause serious psychosocial problems. Regardless of its severity, adolescents with acne have been found to be more likely to have mental health problems, ranging from mild anxiety to shame, low self-esteem, low body image satisfaction, depression and suicidal ideation, compared to adolescents without acne.3,4 It can place a significant burden on the lives of adolescents, with evidence of a decreased quality of life (QoL).4,5

Successful transition from childhood to adulthood involves a combination of biological, psychological and social development. While their balance depends on many factors, given the complex nature of this period, the family is arguably the most important one. The social and emotional development of young individuals is significantly influenced by their parents in many aspects. On the other hand, although skin diseases chiefly have a negative impact on the psychosocial functioning and QoL of adolescents, it is believed that they also have a negative impact on their families. Furthermore, the psychosocial difficulties experienced in the family can cause conflicts and inappropriate parental attitudes. Given the important role of parents in helping their children cope with acne vulgaris, it is essential to understand the impact of the disease on the family and emerging dynamics.

Previous studies have investigated the impact of dermatologic diseases, including acne, on the QoL of children, while the evidence on their impact on their parents has focused primarily on atopic dermatitis.6–9 There is insufficient evidence regarding the impact of acne vulgaris on the QoL of adolescents and their families. Only one recent study has demonstrated the potential burden associated with living with patients with acne vulgaris.10 We conducted a study that focused on the QoL of adolescents with acne and their families. We also aimed to assess the association of QoL in adolescents and families with the severity, duration and location of acne and the response to treatment.

Materials and methodsPopulationWe conducted a cross-sectional case-control study at the… Hospital (hospital name excluded for review) after receiving the approval of the local ethics committee. Individuals aged 12–18 years with acne vulgaris admitted to outpatient dermatology clinics between July 2020 and September 2020 were included after both patients and one of their parents provided written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were (i) dermatologic disease other than acne or manifestations associated with acne, (ii) topical or systemic treatment known to predispose to acne, and (iii) known psychiatric disorder, systemic disease or developmental delay. We recruited healthy controls randomly from individuals referred to outpatient services for routine preventive care visits who had no acne lesions and/or acne treatment history. The inclusion criteria for family members were: (a) age more than 18 years, (b) ability to understand spoken and written Turkish, (c) one parent per participant (either the mother or the father). To avoid potential confounding in the questionnaire results,11 we excluded any family members who had a significant illness or disability that could impact their QoL. After the application of the exclusion criteria, a total of 100 adolescents with acne vulgaris and one parent per adolescent completed the questionnaires.

Data collection and questionnairesFor each patient, we collected a detailed history including data on sociodemographic characteristics, presentation and manifestations of acne, duration of acne (less than 1 year or more than 1 year), acne treatment history (yes/no), satisfaction, and sex of the participating family member (mother/father/caregiver). A physical examination of the face and trunk (chest and back) was performed to assess the acne, with documentation of the clinical characteristics of the acne, including the location of the lesions (face, trunk), and presence of scars (yes/no).

The Global Evaluation Acne (GEA) scale is a scale validated based on the examination of both photographs and acne patients that allows physicians to classify patients into severity categories (Table 1).12 The evaluation of acne and the administration of the GEA scale were performed by the same dermatologist (BT). We excluded patients with GEA scores of 0 from the analysis.

Grading criteria for acne severity in the Global Acne Severity Scale (GEA).12

| Score | Grade | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No lesions | Residual pigmentation and erythema may be seen. |

| 1 | Almost no lesions | A few scattered open or closed comedones and very few papules. |

| 2 | Mild | Easily recognizable: less than half of the face is involved. A few open or closed comedones and a few papules and pustules. |

| 3 | Moderate | More than half of the face is involved. Many papules and pustules, many open or closed comedones. One nodule may be present. |

| 4 | Severe | Entire face is involved, covered with many papules and pustules, open or closed comedones and rare nodules. |

| 5 | Very severe | Highly inflammatory acne covering the face with presence of nodules. |

For the psychosocial evaluation, adolescent participants and their relatives were asked to complete the following questionnaires:

- a)

Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI):

The CDLQI is a self-report questionnaire developed for use in children and adolescents aged 4–16 years that has been applied in several studies, and has been validated for the Turkish population.13,14 It is designed to measure the impact of a dermatologic condition on QoL in terms of the following dimensions: (1) physical symptoms and feelings, (2) leisure (3) work/school, (4) personal relationships, (5) sleep, and (6) treatment. All questions refer to the preceding week. The final CDLQI score is obtained by adding all the item scores (range, 0–30). Higher scores indicate poorer QoL.

- b)

The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI):

This is a 10-item assessment tool used to measure the impact of a dermatologic condition in a child on the health-related QoL (HRQoL) of the caregiver over the past month. The questionnaire has been translated, culturally adapted and validated for use in Turkey.11,15 The questions are rated as “very much” (3 points), “quite a lot” (2 points), “a little” (1 point), and “not at all/ not relevant” (0 points). This instrument includes items that assess the impact of a skin condition in a child or adolescent on the QoL of the family in terms of emotional distress, physical well-being, relationships, other people’s reactions, social life, free time, time spent looking after the child, extra housework, work or education, and daily expenditure. The total score is obtained by the sum of the item scores and ranges between 0 and 30. Higher total FDLQI scores are associated with greater impairment of the caregiver’s HRQoL.11

Statistical analysisThe analysis was performed with the software package SPSS version 23.0. We assessed the shape of the distribution of the data by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We have expressed continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. Categorical data were compared using the χ2 test and differences between non-normally distributed variables were assessed by means of the Mann–Whitney U test. We considered P values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 100 adolescents with acne vulgaris, 100 age- and sex-matched healthy controls and their parents enrolled in the study. In the acne group, the male-to-female ratio was 63:37 and the mean age was 15.36 years (SD, 1.38; range, 12–18). In the control group, the sex distribution was 57% female and 43% male and the mean age was 15.41 years (SD, 1.01; range, 14–17). There were no statistically significant differences between cases and controls in either sex (P = .471) or age (P = .639).

All patients had facial acne and 36% (n = 36) had acne on both face and trunk (chest and back). Grade 2 acne was the most common clinical form (44%), followed by grades 1 and 3 (36% and 20%, respectively). No patients had grade 4 acne vulgaris. Thirty percent of the patients (n = 30) had acne scars. Most (61%) had acne for more than a year. Fifty-two percent of the patients (n = 52) had received treatment for acne, of who 48% (n = 25) had responded well; however, 52% of the treated patients (n = 27) were not satisfied with the results.

The mean CDLQI score of the patients was 7.89 (SD, 5.43; range, 0–24) and the mean FDLQI score of the patients’ parents was 6.01 (SD, 6.11; range, 0–22). The mean CDLQI score of the healthy controls was 3.92 (SD, 3.88; range, 0–15) and the mean FDLQI score of the controls’ parents was 2.12 (SD, 2.91; range, 0–22). There was a statistically significant difference between the case and control groups in the scores of both the CDLQI and the FDLQI (P < .001 for both). The scores of healthy controls were lower compared to the scores of patients with acne.

We found a statistically significant difference in the sex of the participating parents between the case and control groups (P < .001). The mother-to-father ratio was 85:15 in the case group compared to 60:40 in the control group. There were no caregivers other than mothers or fathers in the study.

The analysis of the association of the study variables with the CDLQI and FDLQI scores in the acne group revealed a statistically significant difference in CDLQI scores based on the duration of acne and the response to treatment (Table 2).

Results of the CDLQI and FDLQI in the acne group.

| Variable | CDLQI score, mean ± SD | P | FDLQI score, mean ± SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of patient | Female | 7.92 ± 5.96 | .670 | 5.68 ± 6.37 | .418 |

| Male | 7.83 ± 4.46 | 6.56 ± 5.69 | |||

| Acne severity | Mild | 6.61 ± 4.60 | .161 | 5.47 ± 6.23 | .445 |

| Moderate | 9.15 ± 6.09 | 5.86 ± 5.9 | |||

| Severe | 7.41 ± 4.83 | 7.3 ± 6.48 | |||

| Location | Only face | 7.70 ± 5.68 | .362 | 5.5 ± 6.15 | .101 |

| Face and trunk | 8.22 ± 5 | 6.91 ± 6.01 | |||

| Scarring | Yes | 7.73 ± 5.61 | .723 | 7.2 ± 6.24 | .131 |

| No | 7.95 ± 5.39 | 5.5 ± 6.03 | |||

| Duration | <1 year | 6.3 ± 4.91 | .018 | 6 ± 6.36 | .693 |

| > 1 year | 8.9 ± 5.54 | 6.01 ± 6 | |||

| Response to treatment | Yes | 5.84 ± 4.22 | .012 | 6.16 ± 5.99 | .198 |

| No | 10.18 ± 6.3 | 8.29 ± 6.91 | |||

| Sex of parent | Mother | 7.65 ± 5.19 | .439 | 6.18 ± 6.26 | .590 |

| Father | 9.2 ± 6.65 | 6 ± 5.29 |

CDLQI, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index; FDLQI, Family Dermatology Life Quality Index; SD, standard deviation.

We also analysed the mean scores in individual items of the CDLQI in the acne patients, and found that the highest subscale score corresponded to personal relationships (2.49 points), followed by physical symptoms and feelings (1.68 points), treatment (1.47 points), work/school (1.06 points), sleep (0.61 points), and leisure (0.53 points) (Table 3).

As for the mean scores for individual items of the FDLQI (range, 0–3 points) in families of acne patients, the highest corresponded to emotional distress (1.28 points), followed by the impact on personal relationships (1.19 points), other peoples’ reactions (0.87 points), social life (0.74 points), physical well-being (0.51 points), daily expenditure (0.44 points), time spent looking after the child (0.32 points), free time (0.23 points), work or education (0.22 points), and extra housework (0.19 points) (Table 4).

Mean score in individual items of the FDLQI.

| FDLQI item | Mean score |

|---|---|

| Emotional impact | 1.28 |

| Physical well-being | 0.51 |

| Relationships | 1.19 |

| Other peoples’ reactions | 0.87 |

| Social life | 0.74 |

| Leisure activities | 0.23 |

| Burden of care | 0.32 |

| Extra housework | 0.19 |

| Work or education | 0.22 |

| Extra expenditure | 0.44 |

FDLQI, Family Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Our study found that the families of adolescents with acne vulgaris exhibited a lower QoL, as did the patients themselves. We found a negative association of both poor response to treatment and long duration of acne with QoL in adolescents, but this was not the case in family members.

A growing number of studies is focusing on the impact of dermatologic diseases on the QoL of family members. Martínez-García et al.10 recently conducted a study in patients aged more than 16 years on the effect of acne on the QoL of their relatives. The authors reported that acne had a negative impact on the QoL of 89.4% of individuals sharing the household with affected patients. The DLQI and depression levels in patients with acne were associated with FDLQI scores and depression levels in other members of the household. In addition, individuals who lived with patients with acne showed higher anxiety and depression levels than individuals living with healthy controls. In a pioneering study by Basra et al.,11 the FDLQI was developed and validated as an instrument that allowed a dermatology-specific comprehensive assessment of quality of life in family members of patients with various skin diseases. Although it must be taken into account that acne was but one of several diagnoses included in the spectrum of inflammatory skin conditions (such as eczema or psoriasis), the authors found a significant negative correlation between inflammatory skin disease severity and the QoL of family members. Another finding reported by Dreno et al.12 was the significant impact of recurring acne on both QoL and school or work absenteeism in teenagers as well as adults. Regardless of its severity, recurring acne made patients miss work or school. Adequate care needs to be provided to patients and parents even in cases of mild or moderate acne.

There is an emerging interest in assessing the psychosocial aspects of dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. It is widely recommended to explore psychosocial problems more thoroughly in young individuals, since skin conditions may cause or exacerbate them, given that many previous studies have found a significant decrease in QoL due to other dermatologic problems.16 Patients with acne had significantly higher mean CDLQI scores than control subjects. Regardless of the tools used to evaluate the psychosocial burden of acne, some previous studies have consistently shown that more severe skin lesions are associated with greater impairment in QoL.17–19 In contrast, other studies have found no correlation between the QoL of patients with acne and acne severity.20,21 Krowchuck et al.22 reported that the dissatisfaction of adolescents with the appearance of their face was significantly associated with their own rating of acne severity, but not with the physicians’. In agreement with this, Demircay et al.21 found no correlation between the physicians’ assessment of acne severity and the QoL of patients. The authors emphasized that the assessment of acne severity should include patient self-assessments and acne-specific QoL scales administered by close physicians. The self-assessment of severity may be particularly important in patient evaluations during adolescence.

Although the trial conducted by Sadowsky et al.23 provides more detailed insight on parental empathy and awareness of the psychosocial difficulties of their children, our study found disagreement between the perceptions of adolescents and parents of the impact of the disease. Poor treatment response and long duration of acne were associated with lower QoL for adolescents, contrary to their parents. A possible interpretation is that parents become unsensitised to their children’s problems over time. In the study by Chernyshov et al., similarly to our own study, among the parents of adolescents with atopic dermatitis, parental QoL did not differ for the duration of the disease.24 On the other hand, the studies by Merciniak and Jang et al.,8,9 which assessed patients using a different instrument (Korean Parenting Stress Index) to evaluate the impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on parental QoL, symptom severity was negatively associated with parental QoL. There may be multiple reasons for the discordance of our own findings. First, adolescents are known to have very limited emotional regulation. Adolescents experience positive and negative emotions more frequently and more intensely compared to adults and negative affect persists longer in them compared to other family members.25,26 Second, the discrepancy between the perceptions of parents and children regarding the impact of the response to treatment and the duration of disease on QoL might be due to a decrease in parental QoL itself. This could be considered as a sign of burnout in the parents. In either case, parents should not be neglected in terms of their potential limitations, and they should be supported, given the significant role they play in their children’s treatment process. Also, there is a common misconception about acne, as it is construed as a simple, self-limiting affliction of adolescents by health care providers and the community at large.2 This perception may shift through the use of media and educational materials. Cultural differences, socioeconomic status, parent-child relationship dynamics and individual coping strategies should also be taken into account.

In our study, the item with the highest scores in the FDLQI was the emotional impact experienced due to the child’s skin disease. Acne also affected parents by having an impact on their personal relationships and experiencing problems with other peoples’ reactions. In a study conducted in the parents of 30 children with atopic dermatitis, the emotional impact item also received the highest scores within the FDLQI. Other items that received high ratings frequently were the time spent caring for the relative or partner and increased household expenditure.24 In another study that examined the psychometric properties of the FDLQI among parents and caregivers of children with eczema, the most affected item involved the time spent caring for the relative or partner (e.g., applying cream, administering drugs or caring for their skin).27 In our study, high scores on this item were less frequent. This difference may have been due to the fact that the adolescent patients with acne can take care of their own treatment or skin care, unlike younger patients with eczema.

Based on the CDLQI items, acne in patients seemed to affect their friendships and cause problems with other people in response to their skin. Additional items that most frequently indicated QoL impairment were items 1 and 2, which ask about physical symptoms and feelings (embarrassment or self-consciousness) and item 10, which asks about problems related to the treatment for the skin. The study by Tasoula et al. found that adolescents were less affected by treatment. The authors found that the items of the DLQI most affected by acne corresponded to self-esteem, self-consciousness and physical symptoms (pain and itching), followed by personal relationships, including feelings of worthlessness.28 Embarrassment and self‑consciousness were directly correlated to poor self‑image and self‑esteem; which resulted in a decreased self‑confidence.29

Patients with acne visited the clinics with their mothers more often than with their fathers compared to controls. Women may care more about facial diseases and beauty, so mothers may have been more concerned about acne vulgaris than fathers.

There are limitations to our study. Patients and their parents were evaluated exclusively by means of self-report instruments. Structured psychiatric interviews would have allowed us to gather more reliable evidence on the psychosocial health of the patients. Furthermore, the self-assessment of acne severity by patients in addition to the assessment by physicians may make physicians and parents draw attention to adolescents’ perceptions. Lastly, we were not able to obtain data regarding acne in family members acne during their puberty or the parent-child relationship.

In summary, we aimed to investigate the QoL of the parents of adolescents with acne. Irrespective of severity, patients with acne and their parents had a decreased QoL compared to the normal population. Our findings suggest that parental distress may reflect the distress of the adolescent and in a similar degree. This finding may be indicative of the impact on parental QoL. We recommend informing the parents about the potential negative impact of acne vulgaris on QoL and the associated psychological complications. Assessing the health-related QoL of the family in addition to the QoL of the patient may contribute to improving the outcomes of acne vulgaris.

FundingThe study did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approvalHealth Sciences University, Ankara. Dr A. Yurtaslan, Oncology Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey. File number: 2020-07/698. Date: 08.07.2020.

Informed consentWe obtained written informed consent from patients and families.

Author contributionsStudy conception and design: Burcu Tugrul, Hatice Gamze Demirdag, Cihan Aslan, Ozgul Mustu Koryurek.

Data collection: Burcu Tugrul, Hatice Gamze Demirdag, Cihan Aslan, Ozgul Mustu Koryurek.

Data analysis and interpretation: Burcu Tugrul, Hatice Gamze Demirdag

Writing of manuscript: Burcu Tugrul, Hatice Gamze Demirdag, Cihan Aslan, Ozgul Mustu Koryurek.