Skin-to-skin contact (SSC) offers multiple benefits in preterm newborns (PTNBs), but its implementation can be delayed due to the presence of some devices such as umbilical venous catheters (UVCs). Our objective was to evaluate the practice of SSC in PTNBs in Spanish neonatal units and how the type of catheter affects its initiation.

MethodsWe distributed a survey through the Sociedad Española de Neonatología to Spanish neonatal units, analyzing the timing of SSC initiation and the influence on this practice of the types of devices being used.

ResultsWe obtained a total of 74 responses from centers across all 17 autonomous communities in Spain, of which 67.6% admitted PTNBs of any gestational age or birth weight. In 39.2% of the units, SSC was initiated within the first 24 hours of life (26% in the case of units that admitted PTNBs born before 28 weeks and/or weighing less than 1000 grams).

In 86.5% of the centers, UVC insertion in PTNBs was a routine procedure, and 59.5% reported that the type of inserted catheter affected the timing of SSC initiation. Skin-to-skin contact in infants carrying an UVC was performed in 37.8% of the units, but it was either not performed or rarely performed in the rest.

ConclusionThere is significant variability in the timing of SSC initiation in PTNBs in Spain, and the use of UVCs has been identified as a potential barrier to early implementation. The existence of clinical guidelines or protocols could help improve PTNB care and standardize practices across different units.

El contacto piel con piel (CPP) en recién nacidos prematuros (RNPT) ofrece múltiples beneficios, pero su implementación puede retrasarse debido a la presencia de dispositivos, como los catéteres venosos umbilicales (CVU). El objetivo fue evaluar la práctica del CPP en RNPT en las unidades neonatales españolas y cómo el tipo de catéter afecta su inicio.

MétodosEncuesta difundida a través de la Sociedad Española de Neonatología a las unidades neonatales españolas, analizando el momento de inicio del CPP y la influencia sobre este del tipo de dispositivos empleados.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 74 respuestas, de centros de las 17 comunidades autónomas, de las cuales el 67,6% atienden RNPT de cualquier edad gestacional o peso. El 39,2% de las unidades refiere iniciar el CPP en las primeras 24 horas de vida (26% de unidades que atienden RNPT menores de 28 semanas y/o 1000 gramos).

En el 86,5% de centros la canalización de CVU en RNPT es un procedimiento habitual y el 59,5% señala que el tipo de catéter canalizado influye en el momento de inicio del CPP. En el 37,8% de unidades se realiza CPP con CVU, mientras que el resto o no se realiza o su práctica es excepcional.

ConclusiónExiste gran variabilidad en el inicio de la práctica del CPP en RNPT en España, detectándose el uso del CVU como una posible barrera para su implementación temprana. La existencia de guías clínicas o protocolos podría ayudar a mejorar la asistencia al RNPT y homogeneizar las prácticas entre distintas unidades.

There is evidence that skin-to-skin contact (SSC) offers multiple benefits to preterm newborns (PTNBs) and their parents. They include increased respiratory stability and heart rate regulation, improved thermoregulation and sleep patterns, an analgesic effect for the newborn, a lower incidence of infection, a reduced risk of neonatal mortality and better neurodevelopmental outcomes. In addition, SSC promotes maternal mental health by reducing anxiety and the risk of postpartum depression and has also been associated with increased breast milk production and promotion of parent-infant bonding.1–4

In recent years, studies have been conducted to assess the safety and impact of implementing early SSC in PTNBs, even immediately after birth in the delivery room. Their results indicate that it is a safe practice that could improve cardiovascular stability, thermoregulation and the ability of the infant to handle stress in the first hours of life.5–8 Furthermore, there is evidence that earlier initiation of SSC correlates to a increased daily time spent in SSC during the hospital stay.9 For these reasons, several hospitals in countries with health care technology capabilities similar to those in Spain have assessed the safety of early SSC and proposed various strategies to promote its initiation as early as possible and increase its duration during the hospital stay.10–12

Historically, one of the factors that has acted as a barrier to early initiation of SSC has been the presence of an umbilical catheter. Many health care professionals in neonatal units may consider it a contraindication for SSC in the first days of life due to risks it may pose, such as bleeding, infection or catheter dislodgement or malfunction. In these cases, this leads to a delay in the implementation of SSC until the catheter is removed. Although there is substantial evidence on the complications associated with the use of umbilical venous catheters (UVC) in PTNBs, few studies have specifically evaluated the relationship between the use of these devices and the initiation of SSC.13–18 However, the limited evidence available suggests that SSC in infants carrying a UVC does not increase the risk of catheter-related complications compared to conventional incubator care.16,18

The aim of our study was to assess current practice in neonatal units in Spain regarding SSC in PTNBs in the first days of life and whether the type of catheter used affects the timing of SSC initiation.

Material and methodsAfter an exhaustive review of the available literature, a multidisciplinary team specialized in family-centered developmental care (FCDC) comprised of members of the medical and nursing team of a hospital with a level IIIC neonatal unit19,20 developed a questionnaire.

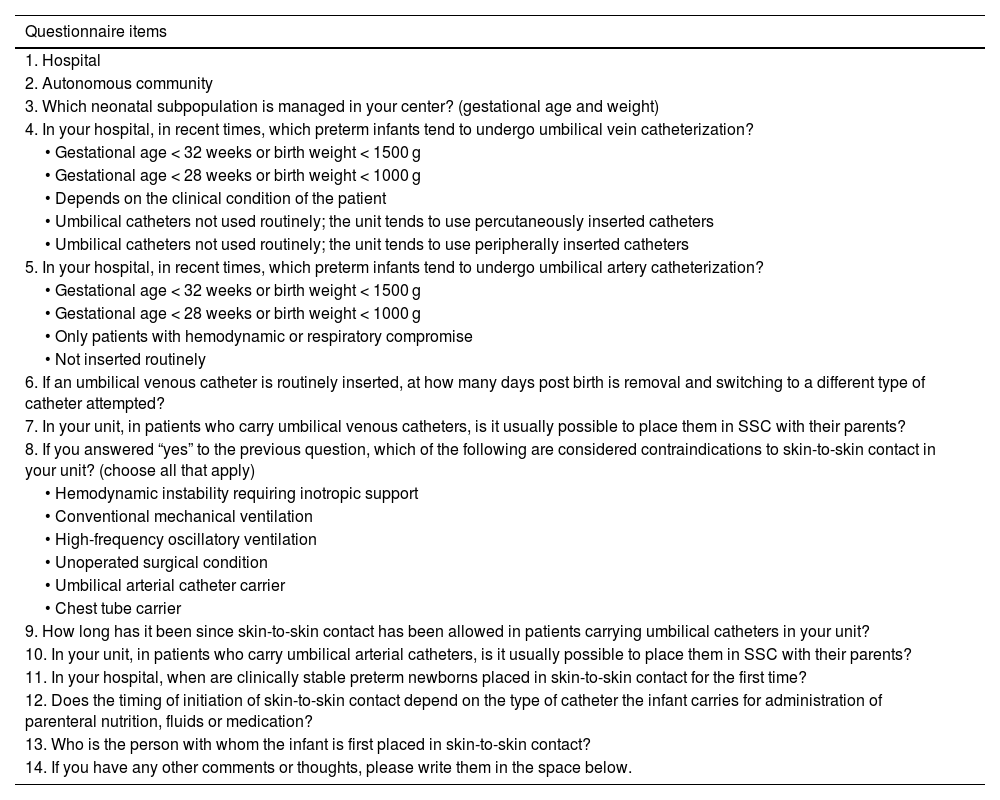

The questionnaire consisted of 14 items, including questions with multiple choice, dichotomous (yes/no) answers and open-ended answer choices. Table 1 presents the questionnaire items.

List of questionnaire items.

| Questionnaire items |

|---|

| 1. Hospital |

| 2. Autonomous community |

| 3. Which neonatal subpopulation is managed in your center? (gestational age and weight) |

| 4. In your hospital, in recent times, which preterm infants tend to undergo umbilical vein catheterization? |

| • Gestational age < 32 weeks or birth weight < 1500 g |

| • Gestational age < 28 weeks or birth weight < 1000 g |

| • Depends on the clinical condition of the patient |

| • Umbilical catheters not used routinely; the unit tends to use percutaneously inserted catheters |

| • Umbilical catheters not used routinely; the unit tends to use peripherally inserted catheters |

| 5. In your hospital, in recent times, which preterm infants tend to undergo umbilical artery catheterization? |

| • Gestational age < 32 weeks or birth weight < 1500 g |

| • Gestational age < 28 weeks or birth weight < 1000 g |

| • Only patients with hemodynamic or respiratory compromise |

| • Not inserted routinely |

| 6. If an umbilical venous catheter is routinely inserted, at how many days post birth is removal and switching to a different type of catheter attempted? |

| 7. In your unit, in patients who carry umbilical venous catheters, is it usually possible to place them in SSC with their parents? |

| 8. If you answered “yes” to the previous question, which of the following are considered contraindications to skin-to-skin contact in your unit? (choose all that apply) |

| • Hemodynamic instability requiring inotropic support |

| • Conventional mechanical ventilation |

| • High-frequency oscillatory ventilation |

| • Unoperated surgical condition |

| • Umbilical arterial catheter carrier |

| • Chest tube carrier |

| 9. How long has it been since skin-to-skin contact has been allowed in patients carrying umbilical catheters in your unit? |

| 10. In your unit, in patients who carry umbilical arterial catheters, is it usually possible to place them in SSC with their parents? |

| 11. In your hospital, when are clinically stable preterm newborns placed in skin-to-skin contact for the first time? |

| 12. Does the timing of initiation of skin-to-skin contact depend on the type of catheter the infant carries for administration of parenteral nutrition, fluids or medication? |

| 13. Who is the person with whom the infant is first placed in skin-to-skin contact? |

| 14. If you have any other comments or thoughts, please write them in the space below. |

The questionnaire was developed in the Google Forms platform and distributed to the members of the Sociedad Española de Neonatología (SENeo, Spanish Society of Neonatology) through its administrative office by means of its mailing list. At the time of distribution, the SENeo had approximately 1400 members. The questionnaire was initially mailed in early March 2023, and a reminder was sent in June 2023. Responses were accepted for 5 months starting from the date of the initial mailing.

A single response was requested and accepted per neonatal unit. Although participation was anonymous and voluntary, in 13 cases we received more than one submission from the same center, so we contacted these centers by email to ask them to combine these submissions into a single response.

We classified participating neonatal units by level, based on the current classification scheme of the SENeo.20

The data were recorded and analyzed using the SPSS Statistics software package, version 29.0 (IBM; Chicago, Illinois, USA). We carried out a descriptive analysis to obtain frequencies and measures of central tendency and dispersion. In the inferential analysis, we used different statistical tests based on the distribution of the data (χ2 test, Fisher exact test, Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test) and considered p values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

ResultsWe received a total of 74 responses from hospitals in the 17 autonomous communities of Spain, with the exception of the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, which did not participate in the survey. The regions with the highest number of participating hospitals were Catalonia (17), the Community of Madrid (13) and Andalusia (8).

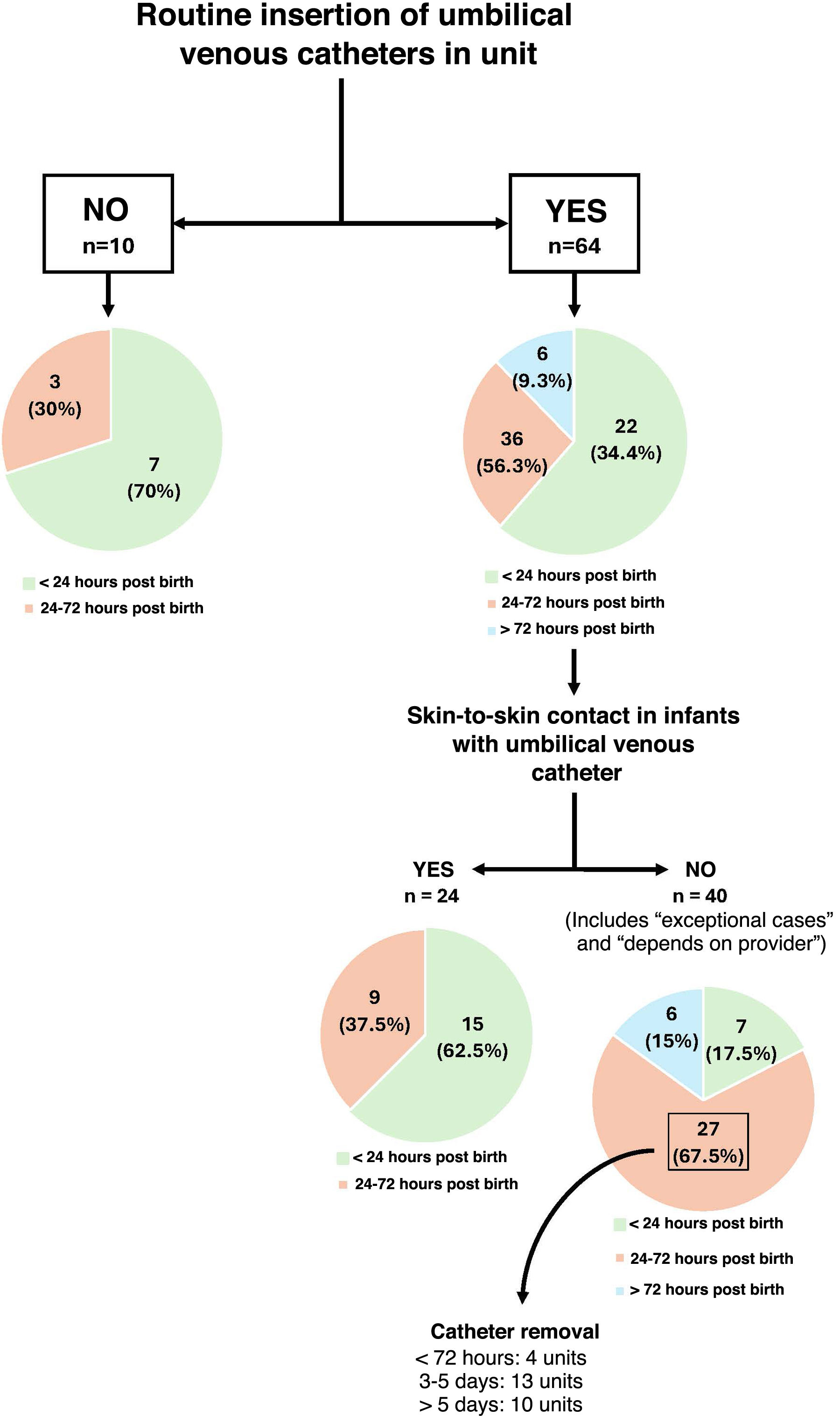

Of the total units, 39.2% reported aiming for initiation of SSC within 24 hours of birth (26% of units that managed patients born before 28 weeks). In contrast, 52.7% of units initiated SSC between 24 and 72 hours post birth and 8.1% from day 4 post birth. Of all units, 59.5% reported that the type of catheter used affected the timing of initiation of SSC.

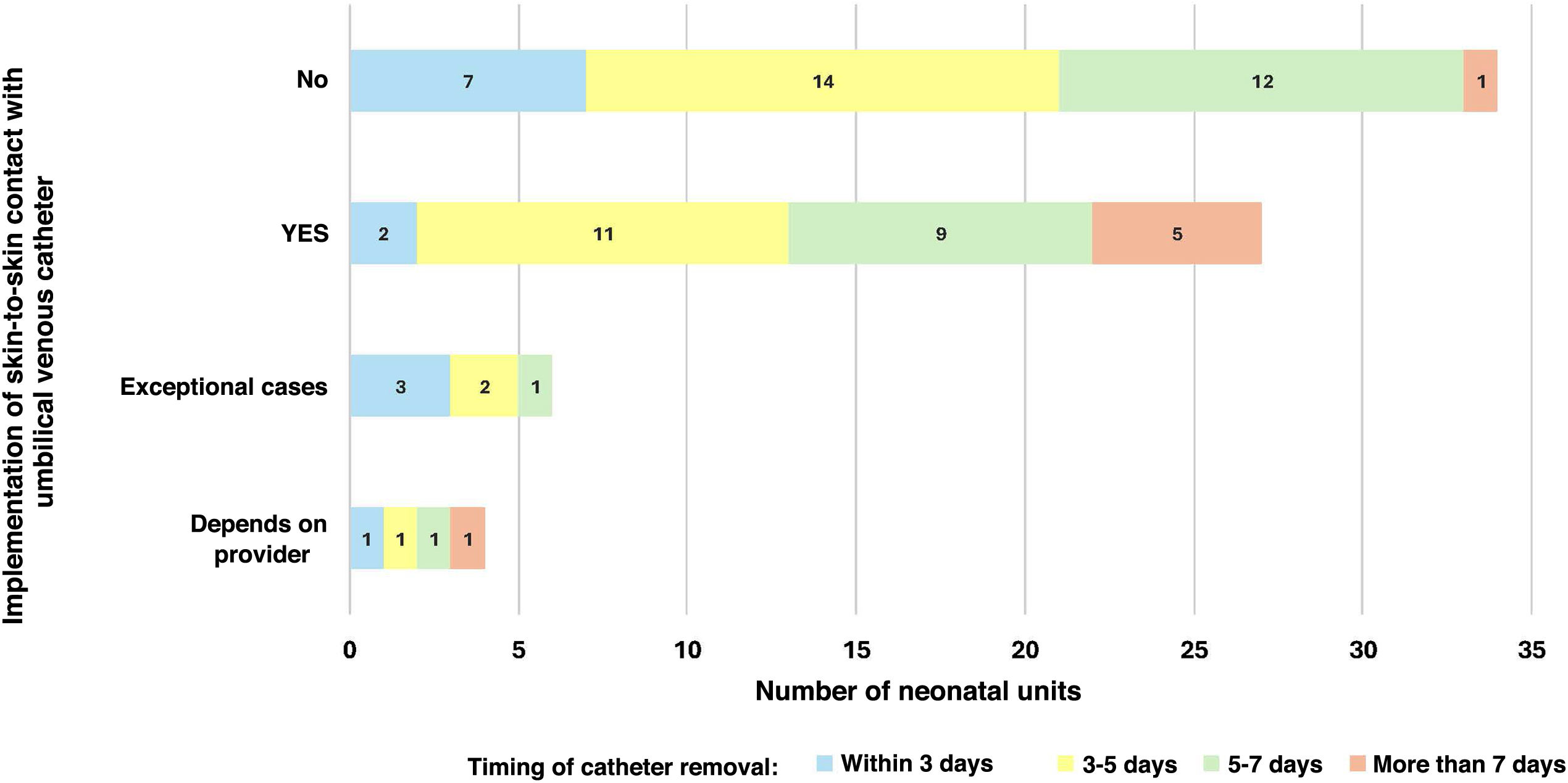

When it came to the practice of SSC in infants with UVCs, 24 units (37.8%) reported implementing it routinely, while 36 (48.6%) reported not implementing it. Six units (8.1%) reported its implementation in exceptional cases, and 4 (5.4%) that the decision was made on a case-by-case basis by the care team. Of the centers that allowed SSC in infants with UVCs, 16 reported that this practice had been in place for more than 5 years, eight that they had adopted it in the past 2 to 5 years and four that it had introduced it within the past 2 years. Fig. 1 presents the distribution of surveyed units based on the implementation of SSC in infants with UVCs and the timing of catheter removal.

Of the surveyed units, 67.6% (50) managed infants of any gestational age or birth weight (level III B or C), 16.2% (12) were level III A units and the remaining 16.2%, level II units.

In 86.5% of the units, umbilical catheterization was a common procedure, while the remaining 13.5% reported routine use of percutaneously or peripherally inserted central catheters instead. In addition, 36.5% of units reported umbilical catheterization of infants born preterm before 32 weeks or with birth weights of less than 1500 g, and 32.4% reported umbilical catheterization only in infants born before 28 weeks or with birth weights under 1000 g.

The use of umbilical arterial catheters was chiefly reserved for infants with hemodynamic instability or respiratory failure (68.9% of units). However, five hospitals reported routine use of umbilical arterial catheters in preterm infants born before 28 weeks or with birth weights under 1000 g. Umbilical catheterization was uncommon in 18 centers.

The UVC dwell time varied between units. In 17.6%, they were usually removed within 3 days, in 37.8% between 3 to 5 days after insertion and in 31.1% between 5 and 7 days from insertion. The remaining units either reported catheter dwell times greater than 7 days or left the question unanswered.

Of the 29 units that initiated SSC within 24 hours of birth, seven did not routinely place an UVC (2 level III B or C, 3 level III A and 4 level II units) and 13 reported implementation of SSC in infants carrying UVCs for more than five years. Fig. 2 shows the timing of initiation of SSC in relation to the use of UVC in the units.

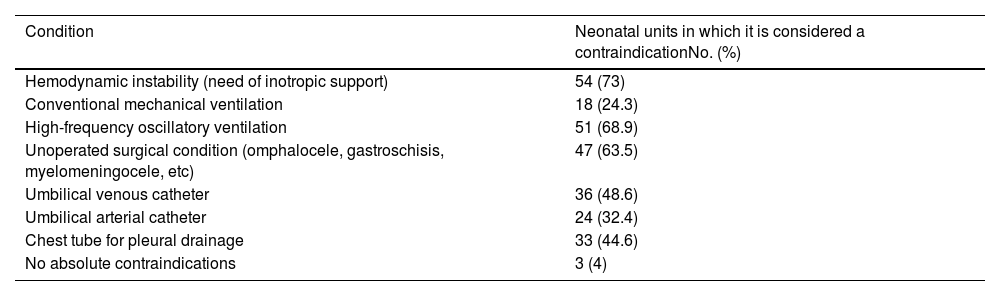

Table 2 presents the contraindications to SSC reported by neonatal units in Spain. Only three reported having no absolute contraindications for implementation of SSC (two level III B and one level II).

Contraindications to the implementation of skin-to-skin contact in Spanish neonatal units.

| Condition | Neonatal units in which it is considered a contraindicationNo. (%) |

|---|---|

| Hemodynamic instability (need of inotropic support) | 54 (73) |

| Conventional mechanical ventilation | 18 (24.3) |

| High-frequency oscillatory ventilation | 51 (68.9) |

| Unoperated surgical condition (omphalocele, gastroschisis, myelomeningocele, etc) | 47 (63.5) |

| Umbilical venous catheter | 36 (48.6) |

| Umbilical arterial catheter | 24 (32.4) |

| Chest tube for pleural drainage | 33 (44.6) |

| No absolute contraindications | 3 (4) |

The findings of this survey, which included neonatal units from nearly the entire Spanish territory, revealed substantial variation in clinical practice in relation to early initiation of SSC, particularly with regard to its implementation in the context of umbilical catheterization.

Our study revealed that fewer than 40% of units attempted to initiate SSC within 24 hours of birth, and the percentage was even lower for level III B and III C units. A number of studies support the multiple benefits of SSC, even immediately after birth in the delivery room, which justifies its early implementation, although it is true that, for infants born before 28 weeks, the evidence is scarce and more studies including this subset of patients are still needed.5–8,21,22 Furthermore, some studies have found that early initiation of SSC promotes an increase in the overall time spent in SSC during the hospital stay.9,21 In consequence, the World Health Organization recommends initiation of SSC in preterm and low birth weight infants as soon as possible after birth and provision of kangaroo mother care as many hours as possible each day during the hospital stay.23 Based on our results in this care setting, there is still considerable room for improvement in Spanish neonatal units, especially those managing the most vulnerable infants, who seem to experience the greatest difficulties in the early implementation of this approach.

One of the most frequently described barriers to the practice of SSC and kangaroo care in the first days of life is the use of various medical devices, including UVCs.11,17 We found that the use of UVCs was common in Spain, especially in the most premature babies, as it was reported by nearly 70% of units managing neonates born before 28 weeks of gestation or with birth weights of less than 1000 g. In comparison, umbilical artery catheterization was less frequent. Our survey corroborates that the presence of an UVC posed a barrier to early SSC in Spain, as fewer than four out of ten units reported initiation of SSC while preterm infants carried an UVC. In addition, a majority of the units that did not implement kangaroo care in infants with an UVC also reported that the catheter was removed after 72 hours of life, which means that in these units SSC is most likely delayed to at least day 4 post birth at the earliest.

Although our survey did not specifically explore the reasons why the presence of an UVC is considered a contraindication for SSC, it is likely that many providers perceive it as a contraindication due to the potential associated risks, such as bleeding, infection or catheter displacement or malfunction. Although numerous studies in the literature have analyzed the complications arising from the use of UVCs in preterm infants, few have directly assessed the risks associated with these devices in the context of SSC.13–18 However, although the available evidence is limited, the studies that have analyzed the incidence of complications in newborns placed in SSC compared to those who remain in the incubator until catheter removal have not found a significant increase in complications and have even observed a reduced incidence for some of them.16,18 These results indicate that, if the preterm infant is stable enough for kangaroo care to be considered, placing the infant in SSC even with an UVC is not only feasible but could allow the infant to enjoy the beneficial effects of this approach earlier, and, after all, this is one of the interventions with the strongest evidence supporting the positive impact in the promotion of infant growth and neurodevelopment and parent-infant bonding.16,18

Aside from umbilical catheters, the most frequent barriers to the implementation of SSC in Spanish neonatal units identified in our study were hemodynamic instability requiring inotropic support, invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), especially high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, unoperated surgical conditions and chest drainage. Only three units reported having no absolute contraindications for SSC, of which one was a level II unit and, therefore, managed less complex patients. Observational studies of kangaroo care in mechanically ventilated PTNBs have shown that it is a safe practice.11,24,25 It was encouraging to find that, in agreement with the previous literature, less than a quarter of neonatal units in Spain currently consider IMV a contraindication for kangaroo care. Although there is no previous evidence on the practice of SSC in ventilated preterm infants in Spain, our findings may reflect a significant improvement in recent years. However, there is still room for improvement, especially in infants receiving high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, in whom, except in the case of acute respiratory deterioration, this intervention may not pose a much higher risk compared to SSC in infants receiving conventional IMV.

In addition to medical devices, we must consider the logistical and organizational barriers that may hinder early initiation of SSC in Spanish neonatal units. Factors such as the availability of adequate spaces for this practice, the complexity of safely moving the newborn out of the incubator due to the layout of some units, the lack of comfortable seating for family members and the need for training and confidence of health care staff may pose significant challenges. Overcoming these obstacles requires careful planning of the infrastructure and equipment of neonatal units as well as adequate training of health care professionals.

In this context, the lack of specialized training and standardized protocols can be a limiting factor. The implementation of SSC, especially in the most vulnerable patients, requires training of health care staff for the acquisition of specific technical skills that will allow them to develop the confidence to implement kangaroo care safely. The development of simulation-based continuing education programs that address not only technical aspects but also communication skills and the benefits of SSC could help increase awareness of its importance among professionals and promote changes in clinical practice. Similarly, the provision of specific training courses by units that have already overcome these barriers to professionals from other centers could also help reduce disparities between centers and promote increasingly uniform delivery of kangaroo care throughout Spain.

The heterogeneity in the practices of different neonatal units evinced in our survey highlights the need to develop evidence-based clinical guidelines to standardize the delivery of kangaroo care in preterm infants, especially in relation to the use of devices such as umbilical catheters. Recently, the FCDC Group of the Sociedad Española de Enfermería Neonatal (Spanish Society of Neonatal Nursing) published its Consensus Guideline for Kangaroo Mother Care.26 This document already states that neither IMV nor the use of central venous catheters, including umbilical catheters, should be considered contraindications for SSC. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of clinical guidelines, adequate protocols and continuous training of health care workers to guarantee patient safety, the confidence of professionals in regard to moving the infant for SSC and infant monitoring during it, and adequate education of families about the benefits of kangaroo care and the importance of spending as much time as possible with SSC during the hospital stay. This consensus document can be a useful tool to standardize kangaroo care practices in neonatal units throughout Spain.

One of the main strengths of this study is that it addresses a crucial issue in the care of PTNBs, namely, SSC, an intervention that has consistently demonstrated its beneficial effects over time. This survey facilitated the identification of barriers and areas for improvement in the practice of SSC in Spain, especially with regard to the presence of devices such as UVCs. In addition, the high response rate guaranteed broad geographical coverage, with a representative sample of units offering different levels of care from almost the entire national territory, thus providing a comprehensive and realistic overview of current real-world practices.

The main limitation of the study is its subjectivity, as the reported data was based on the perspective of participating professionals, which could introduce biases related to their personal interpretation of the usual practices in each unit. Furthermore, as it was a survey, we did not collect data on associated clinical outcomes, which limits our ability to analyze the relationship between clinical practices and patient outcomes. On the other hand, although our survey identified several barriers to the implementation of SSC, it focused on the use of catheters and did not explore the reasons why certain practices are considered contraindications. Furthermore, although we know the approximate number of SENeo members at the time the questionnaire was distributed, we do not have accurate information on the total number of neonatal units that received it, which limits our ability to determine how representative the survey was, and it is possible that certain units, especially high-level ones, are overrepresented compared to level II units, which could be a source of bias in favor of more restrictive practices.

In conclusion, the results of this survey reveal considerable heterogeneity in kangaroo care practices in PTNBs in Spain, especially in relation to the use of medical devices such as umbilical catheters. This variability evinces the need for further research and the development of clinical guidelines to promote greater uniformity in the delivery of neonatal care. The recent consensus document on kangaroo mother care may be a useful tool to standardize kangaroo mother care across neonatal units in Spain. These aspects need to be reevaluated in upcoming years to assess the impact of the recently published guidelines.