Adolescence is a transitional stage of development, with imprecise age limits, during which the individual progressively develops the maturity required for decision-making. Sexual consent is part of the right to sexual freedom, a fundamental right that must be promoted and taught from childhood. At present, there is considerable social alarm in relation to the risks associated with the increased consumption of pornography from an early age. Pornography provides a distorted image of sexual relations that does not feature the elements of consent or respect to the other, commonly offering visual content that normalizes violence, humiliation and the objectification of human beings. The lack of comprehensive sex education with an affective component, combined with the emergence of “new pornography” as a school of sexuality, means that adolescents may come to accept and/or normalize nonconsensual sexual relations that can violate the dignity of the individual. The aim of the study was to perform a critical review of the literature available in the main databases published from 2015 to present in order to characterize the consumption of pornography by adolescents and its associated risks. Lastly, it addresses individual and social factors involved in sexual consent, as well as aspects related to the autonomy required for the individual to be able to consent.

La adolescencia es una etapa evolutiva y de transición, cuyos límites de edad son poco precisos y durante la cual se produce una adquisición progresiva de la madurez necesaria para la toma de decisiones. El consentimiento sexual forma parte del derecho a la libertad sexual, un derecho fundamental que se debe fomentar y educar desde la infancia. Actualmente existe una gran alarma social motivada por los riesgos asociados al consumo aumentado de pornografía a edades tempranas. La pornografía aporta una imagen distorsionada de la relación sexual en la que no existe la figura del consentimiento y el respeto al otro, siendo habitual imágenes donde se normaliza la violencia, la humillación y la cosificación de la persona. La carencia de una educación afectivo sexual integral unido a la irrupción de la «nueva pornografía» como escuela de la sexualidad, hace que el/la adolescente pueda aceptar y/o normalizar relaciones sexuales no consentidas y que pueden vulnerar la dignidad de la persona. En el presente estudio se realiza una revisión crítica de la literatura existente, en las principales bases de datos desde el año 2015 hasta la actualidad, con el fin de conocer los datos de consumo y riesgos asociados al uso de pornografía en la adolescencia. Por último, se reflexiona sobre los factores individuales y sociales que intervienen en el consentimiento sexual, así como los aspectos relacionados con la autonomía de la persona para poder consentir.

Adolescence is a crucial stage in human development marked by significant physical, emotional and social changes. It is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood in which young people begin to explore their identity, their interpersonal relationships and their sexuality. During these years, adolescents do not only experience biological growth but also face challenges as they develop their autonomy and start making decisions that will affect their wellbeing in the long term.

The development of sexuality in adolescence is a complex process influenced by a variety of factors, such as education, culture and the family and social environments. It is at this stage that young people begin to form their own beliefs and attitudes about sex and relationships. However, the lack of comprehensive sex education can result in the misunderstanding of fundamental concepts, such as consent. In the absence of appropriate education on the subject, many adolescents may be exposed to distorted representations of sexuality, such as those commonly found in pornography, that can have a negative impact on their understanding of consent and healthy relationships.

Sexual consent, a key element in any intimate relationship, refers to the ability to give permission in a clear, conscious and voluntary way. It is essential that adolescents learn about this concept from an early age, as it enables them to establish respectful and equitable relationships. In circumstances in which information about sexuality is frequently confusing or scarce, it is crucial to promote an open and educational dialogue to empower young people to understand their right to decide and to set limits in their sexual interactions. This approach not only contributes to their personal development, but also fosters a culture of respect and responsibility in the sexual lives of adolescents.

In our society, there is currently debate as to whether the legal age of consent should be upheld, which is set by Law 1/2015 at 16 years, or whether sexual relations at a younger age should be tolerated; article 183 bis of the same law contemplates an exception to this minimum as long as the involved individuals are of similar age and maturity.1

Given this exception, recognized by the law, we ought to consider whether there is an age under which it would no longer be applicable, and whether providers have the necessary resources to determine whether the required balance in maturity (insofar as it affects decision-making) does actually exist.

Today, the availability of pornography meets the three features of what Cooper labeled as the “Triple-A Engine” in 1998: accessibility, affordability, and anonymity. Adolescents consume pornography in the privacy of their rooms, chiefly through their mobile phones, anonymously and for free.2 The control measures implemented to prevent access of minors to these sites are lax, as simply stating that the user is of age may suffice to allow access and visualization of contents that may be inappropriate from an early age.

In this article, we present a critical narrative review of the literature to answer the following three questions:

- •

What type and scope of sexuality education are our adolescents receiving?

- •

What are the patterns of pornography use and the associated risks in this age group?

- •

What individual and social determinants are associated with sexual consent in adolescence?

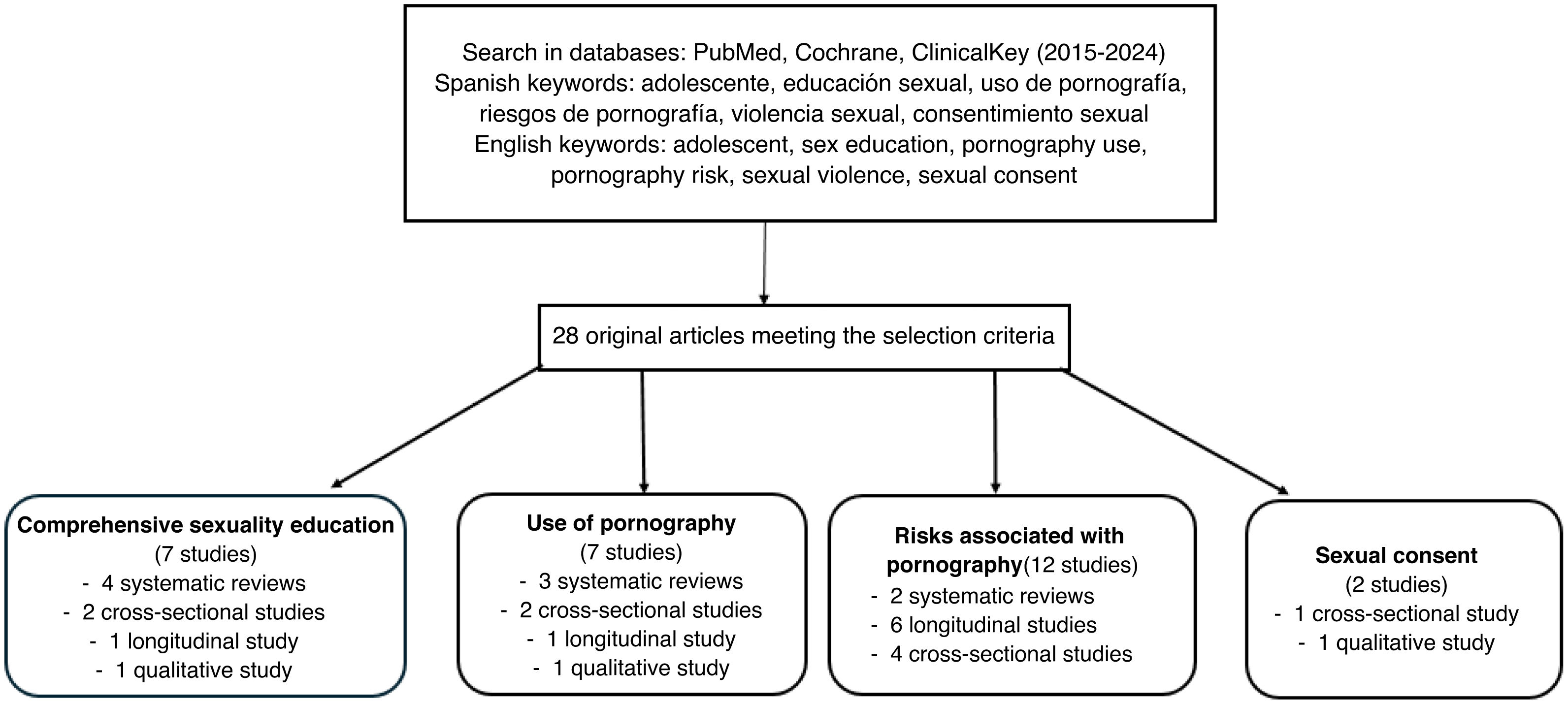

We conducted a review of scientific articles published between 2015 and 2023, indexed in the PubMed, ClinicalKey and Cochrane databases (Fig. 1). We used the following search terms in both Spanish and English: adolescence, sex education, pornography, risks, sexual violence and sexual consent.

The review included studies with participants aged 10–17 years, as we found no studies on the subject including children under 10 years. We included one study on problematic sexual behavior in minors and its association with the exposure to sexual content and one qualitative study that analysed parental responses to the discovery of the early exposure of their young children before age 12 years.

We reviewed a total of 28 publications, of which seven focused on education and sexual health, 19 on aspects related to pornography and the rest on aspects pertaining to consent and associated factors (Table 1).

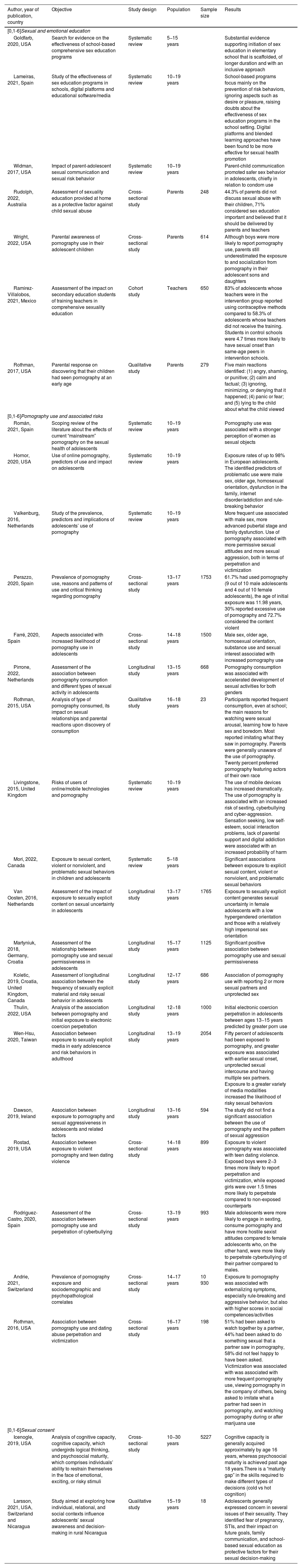

Articles included in the review.

| Author, year of publication, country | Objective | Study design | Population | Sample size | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1-6]Sexual and emotional education | |||||

| Goldfarb, 2020, USA | Search for evidence on the effectiveness of school-based comprehensive sex education programs | Systematic review | 5−15 years | Substantial evidence supporting initiation of sex education in elementary school that is scaffolded, of longer duration and with an inclusive approach | |

| Lameiras, 2021, Spain | Study of the effectiveness of sex education programs in schools, digital platforms and educational software/media | Systematic review | 10−19 years | School-based programs focus mainly on the prevention of risk behaviors, ignoring aspects such as desire or pleasure, raising doubts about the effectiveness of sex education programs in the school setting. Digital platforms and blended learning approaches have been found to be more effective for sexual health promotion | |

| Widman, 2017, USA | Impact of parent-adolescent sexual communication and sexual risk behavior | Systematic review | 10−19 years | Parent-child communication promoted safer sex behavior in adolescents, chiefly in relation to condom use | |

| Rudolph, 2022, Australia | Assessment of sexuality education provided at home as a protective factor against child sexual abuse | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 248 | 44.3% of parents did not discuss sexual abuse with their children, 71% considered sex education important and believed that it should be delivered by parents and teachers |

| Wright, 2022, USA | Parental awareness of pornography use in their adolescent children | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 614 | Although boys were more likely to report pornography use, parents still underestimated the exposure to and socialization from pornography in their adolescent sons and daughters |

| Ramirez-Villalobos, 2021, Mexico | Assessment of the impact on secondary education students of training teachers in comprehensive sexuality education | Cohort study | Teachers | 650 | 83% of adolescents whose teachers were in the intervention group reported using contraceptive methods compared to 58.3% of adolescents whose teachers did not receive the training. Students in control schools were 4.7 times more likely to have sexual onset than same-age peers in intervention schools. |

| Rothman, 2017, USA | Parental response on discovering that their children had seen pornography at an early age | Qualitative study | Parents | 279 | Five main reactions identified: (1) angry, shaming, or punitive; (2) calm and factual; (3) ignoring, minimizing, or denying that it happened; (4) panic or fear; and (5) lying to the child about what the child viewed |

| [0,1-6]Pornography use and associated risks | |||||

| Román, 2021, Spain | Scoping review of the literature about the effects of current “mainstream” pornography on the sexual health of adolescents | Systematic review | 10−19 years | Pornography use was associated with a stronger perception of women as sexual objects | |

| Hornor, 2020, USA | Use of online pornography, predictors of use and impact on adolescents | Systematic review | 10−19 years | Exposure rates of up to 98% in European adolescents. The identified predictors of problematic use were male sex, older age, homosexual orientation, dysfunction in the family, internet disorder/addiction and rule-breaking behavior | |

| Valkenburg, 2016, Netherlands | Study of the prevalence, predictors and implications of adolescents’ use of pornography | Systematic review | 10−19 years | More frequent use associated with male sex, more advanced pubertal stage and family dysfunction. Use of pornography associated with more permissive sexual attitudes and more sexual aggression, both in terms of perpetration and victimization | |

| Perazzo, 2020, Spain | Prevalence of pornography use, reasons and patterns of use and critical thinking regarding pornography | Cross-sectional study | 13−17 years | 1753 | 61.7% had used pornography (9 out of 10 male adolescents and 4 out of 10 female adolescents), the age of initial exposure was 11.98 years, 30% reported excessive use of pornography and 72.7% considered the content violent |

| Farré, 2020, Spain | Aspects associated with increased likelihood of pornography use in adolescents | Cross-sectional study | 14−18 years | 1500 | Male sex, older age, homosexual orientation, substance use and sexual interest associated with increased pornography use |

| Pirrone, 2022, Netherlands | Assessment of the association between pornography consumption and different types of sexual activity in adolescents | Longitudinal study | 13−15 years | 668 | Pornography consumption was associated with accelerated development of sexual activities for both genders |

| Rothman, 2015, USA | Analysis of type of pornography consumed, its impact on sexual relationships and parental reactions upon discovery of consumption | Qualitative study | 16−18 years | 23 | Participants reported frequent consumption, even at school; the main reasons for watching were sexual arousal, learning how to have sex and boredom. Most reported imitating what they saw in pornography. Parents were generally unaware of the use of pornography. Twenty percent preferred pornography featuring actors of their own race |

| Livingstone, 2015, United Kingdom | Risks of users of online/mobile technologies and pornography | Systematic review | 10−19 years | The use of mobile devices has increased dramatically. The use of pornography is associated with an increased risk of sexting, cyberbullying and cyber-aggression. Sensation seeking, low self-esteem, social interaction problems, lack of parental support and digital addiction were associated with an increased probability of harm | |

| Mori, 2022, Canada | Exposure to sexual content, violent or nonviolent, and problematic sexual behaviors in children and adolescents | Systematic review | 5−18 years | Significant associations between exposure to explicit sexual content, violent or nonviolent, and problematic sexual behaviors | |

| Van Oosten, 2016, Netherlands | Assessment of the impact of exposure to sexually explicit content on sexual uncertainty in adolescents | Longitudinal study | 13−17 years | 1765 | Exposure to sexually explicit content generates sexual uncertainty in female adolescents with a low hypergendered orientation and those with a relatively high impersonal sex orientation |

| Martyniuk, 2018, Germany, Croatia | Assessment of the relationship between pornography use and sexual permissiveness in adolescents | Longitudinal study | 15−17 years | 1125 | Significant positive association between pornography use and sexual permissiveness |

| Koletic, 2019, Croatia, United Kingdom, Canada | Assessment of longitudinal association between the frequency of sexually explicit material and risky sexual behavior in adolescents | Longitudinal study | 12−17 years | 686 | Association of pornography use with reporting 2 or more sexual partners and unprotected sex |

| Thulin, 2022, USA | Analysis of the association between pornography and initial exposure to electronic coercion perpetration | Longitudinal study | 12−18 years | 1000 | Initial electronic coercion perpetration in adolescents between ages 13−15 years predicted by greater porn use |

| Wen-Hsu, 2020, Taiwan | Association between exposure to sexually explicit media in early adolescence and risk behaviors in adulthood | Longitudinal study | 13−19 years | 2054 | Fifty percent of adolescents had been exposed to pornography, and greater exposure was associated with earlier sexual onset, unprotected sexual intercourse and having multiple sex partners. Exposure to a greater variety of media modalities increased the likelihood of risky sexual behaviors |

| Dawson, 2019, Ireland | Association between exposure to pornography and sexual aggressiveness in adolescents and related factors | Longitudinal study | 13−16 years | 594 | The study did not find a significant association between the use of pornography and the pattern of sexual aggression |

| Rostad, 2019, USA | Association between exposure to violent pornography and teen dating violence | Cross-sectional study | 14−18 years | 899 | Exposure to violent pornography was associated with teen dating violence. Exposed boys were 2−3 times more likely to report perpetration and victimization, while exposed girls were over 1.5 times more likely to perpetrate compared to non-exposed counterparts |

| Rodriguez-Castro, 2020, Spain | Assessment of the association between pornography use and perpetration of cyberbullying | Cross-sectional study | 13−19 years | 993 | Male adolescents were more likely to engage in sexting, consume pornography and have more hostile sexist attitudes compared to female adolescents who, on the other hand, were more likely to perpetrate cyberbullying of their partner compared to males. |

| Andrie, 2021, Switzerland | Prevalence of pornography exposure and sociodemographic and psychopathological correlates | Cross-sectional study | 14−17 years | 10 930 | Exposure to pornography was associated with externalizing symptoms, especially rule-breaking and aggressive behavior, but also with higher scores in social competences/activities |

| Rothman, 2016, USA | Association between pornography use and dating abuse perpetration and victimization | Cross-sectional study | 16−17 years | 198 | 51% had been asked to watch together by a partner, 44% had been asked to do something sexual that a partner saw in pornography, 58% did not feel happy to have been asked. Victimization was associated with was associated with more frequent pornography use, viewing pornography in the company of others, being asked to imitate what a partner had seen in pornography, and watching pornography during or after marijuana use |

| [0,1-6]Sexual consent | |||||

| Icenogle, 2019, USA | Analysis of cognitive capacity, cognitive capacity, which undergirds logical thinking, and psychosocial maturity, which comprises individuals’ ability to restrain themselves in the face of emotional, exciting, or risky stimuli | Cross-sectional study | 10−30 years | 5227 | Cognitive capacity is generally acquired approximately by age 16 years, whereas psychosocial maturity is achieved past age 18 years.There is a “maturity gap” in the skills required to make different types of decisions (cold vs hot cognition) |

| Larsson, 2021, USA, Switzerland and Nicaragua | Study aimed at exploring how individual, relational, and social contexts influence adolescents’ sexual awareness and decision-making in rural Nicaragua | Qualitative study | 15−19 years | 18 | Adolescents generally expressed concern in several issues of their sexuality. They identified fear of pregnancy, STIs, and their impact on future goals, family communication, and school-based sexual education as protective factors for their sexual decision-making |

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Most of the studies in the literature have cross-sectional or longitudinal designs with data collection through self-administered questionnaires. Thus, there is a risk of self-selection bias, with participation of adolescents who are more sexually experienced, and of attrition bias, due to a lack of interest in adolescents or the parents refusing to consent to their participation. Conducting other types of study that could yield more rigorous evidence poses certain ethical dilemmas, as it would be difficult to specifically ask minors what they have seen without introducing concepts of a sexual nature, something that could hardly be approved by a research ethics committee.3 We included three qualitative studies conducted in Boston.

Technologies and social practices evolve so quickly that scientific evidence becomes obsolete before studies are published, which is why it would be reasonable to assume that the actual figures may be higher than reported.3

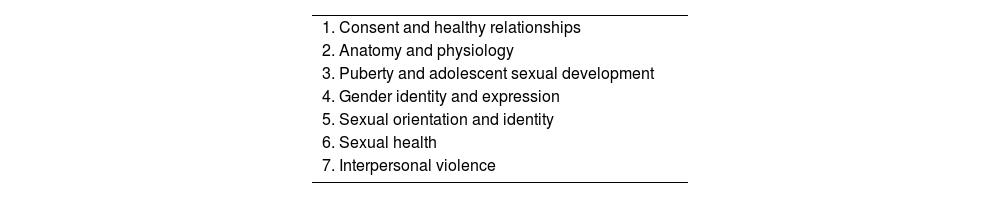

Results and discussionDue to the format of the conducted review, we the results and discussion are presented togetherComprehensive sexuality education in SpainThe Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) defines “comprehensive sexuality education” as education on human sexuality from a broad perspective, including the sexual knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors of individuals. In 2020, SIECUS published updated national sexuality education standards guide schools regarding the core contents and skills required to deliver effective sex education to students (Table 2).3

Comprehensive sexuality education. Topic areas (SIECUS).

| 1. Consent and healthy relationships |

| 2. Anatomy and physiology |

| 3. Puberty and adolescent sexual development |

| 4. Gender identity and expression |

| 5. Sexual orientation and identity |

| 6. Sexual health |

| 7. Interpersonal violence |

SIECUS, Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States.

Comprehensive sexuality education should start in primary school, be scaffolded across grades and have an inclusive curriculum.4 Although this is the approach that should be pursued, most sex education programs in Spain have a biological approach, focusing on the prevention of risk behaviors and leaving out subjects such as pleasure, desire or the concept of sexuality as an intrinsic aspect of development.

Organic Law 3/2020 on education refers to comprehensive sexuality education as a multidisciplinary subject spanning different stages of education and gives free rein to schools and teachers as to whether and how to teach it. Thus, we may conclude that the Spanish laws that regulate the education system allow, but do not guarantee, sexuality education. This position goes against the call of the UNESCO for governments to make comprehensive sexuality education mandatory and continuous across the different education stages, and have it explicitly included in curricula as such.5

The global status report of the UNESCO on sexuality education, published in 2022, mentions Spain as one of the 23 out of a total of 115 evaluated countries where comprehensive sexuality education was not included routinely in the educational curriculum.5

Discussions about sexuality with parents and teachers improve sexual behavior in adolescents, contributing to safer and more respectful practices.6–9

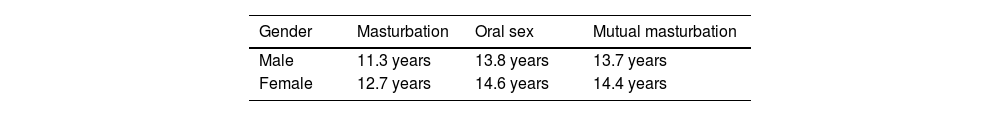

In Spain, the mean age at sexual debut is of around 17 years in the population aged 15–29 years (INJUVE 2019).10 Previous studies in adolescents aged 15–18 years reported a mean age at first intercourse with penetration of 15 years.11Table 3 presents data on other types of sexual activity.10

In 2015, Pérez and Candel reported that a quarter of the adolescents that participated in their survey did not consider condoms safe and felt they interfered with sexual satisfaction.12

The incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is on the rise in practically every demographic group, including adolescents. According to the report by the Centro Nacional de Epidemiología (National Center for Epidemiology of Spain), the incidence of gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis doubled in youth aged 15–19 years in Spain between 2016 and 2019.13

Use of pornography by adolescents and associated risksIn 2020, Hornor reported prevalences of exposure nearing 98% in some European countries, such as Germany or Switzerland.2 The same year, Save the Children of adolescents aged 13–17 years in the Community of Madrid and found that nine out of ten male adolescents, compared to four out of ten female adolescents, reported having seen pornography. The first exposure occurred at 11.89 years in boys compared to 12.3 years in girls. In addition, 20.6% reported access to online pornography more than once a week and, while most respondents considered their use responsible, 30% expressed that their use of pornography exceeded their intended limits.14

In general, parents underestimate the use of pornography in adolescents.15 In 2015, Rothman et al. published the findings of a qualitative study on parental reactions upon discovering that their children, aged less than 12 years, had seen pornography. While many responded calmly and saw it as an opportunity to discuss the subject, four percent reacted violently, and a similar proportion avoided conflict or pretended not to know about pornography to avoid discussing it. Regarding information by pediatricians, parents held opposing stances, with some wanting providers to offer informational pamphlets on how to deal with the subject and others considering this would be harmful because if children saw these materials it could contribute to “sexualizing” them.16

There is a pattern of pornography use characterized by initial unintentional exposure, typical of young adolescents, and a more advanced pattern of intentional consumption for pleasure-seeking, either through self-exploration or arousal, characteristic of older adolescents.17,18

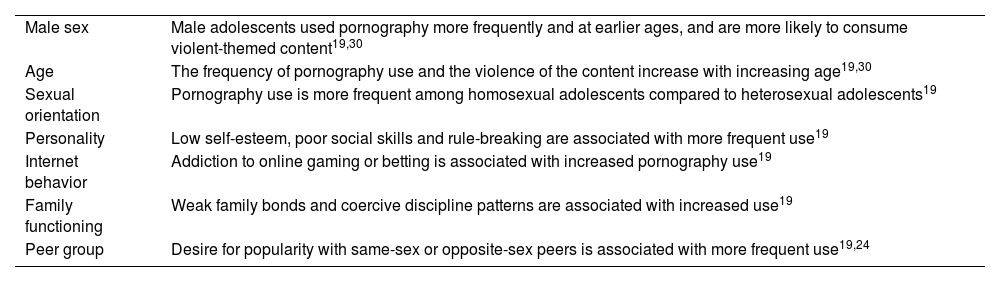

Although exposure to pornography is widespread, the literature describes different factors that may predict an increased use, summarized in Table 4.19

Predictors of pornography use.

| Male sex | Male adolescents used pornography more frequently and at earlier ages, and are more likely to consume violent-themed content19,30 |

| Age | The frequency of pornography use and the violence of the content increase with increasing age19,30 |

| Sexual orientation | Pornography use is more frequent among homosexual adolescents compared to heterosexual adolescents19 |

| Personality | Low self-esteem, poor social skills and rule-breaking are associated with more frequent use19 |

| Internet behavior | Addiction to online gaming or betting is associated with increased pornography use19 |

| Family functioning | Weak family bonds and coercive discipline patterns are associated with increased use19 |

| Peer group | Desire for popularity with same-sex or opposite-sex peers is associated with more frequent use19,24 |

As regards the risks associated with pornography use, we identified the following in the literature review:

- •

Sexual self-development: pornography use is associated with greater sexual preoccupancy and strong cognitive engagement in sexual issues, sometimes to the exclusion of other thoughts.19 A tendency to imitate behaviors seen in pornographic content and an increased probability of engaging in sexual aggression has been reported.20

- •

Moral incongruence: it refers to the conflict that may emerge between the use of pornography and the pre-existing beliefs about sexuality in the adolescent.20 Male adolescents who tend to engage in aggressive or offensive behaviors in their relationships and exhibit dominance toward their partners (hypermasculine gender orientation) and female adolescents who accept male dominance (hyperfeminine gender orientation), exhibit lesser incongruence and respond less critically to consumed pornographic content.19,21

- •

Early sexual activity: a study published by Rasmussen and Bierman in 201822 found that adolescents who reported early and regular use of pornography had an earlier sexual debut and reported double the number of partners compared to adolescents who were not exposed.23,24 There is evidence of an association between asking the partner to watch pornography and the imitation of the practices seen in pornography.25,26

- •

Risky sexual behaviors: studies in the literature have yielded heterogeneous results. A prospective psychosocial study (PROBIOPS) conducted in adolescents in Croatia did not find significant associations, while a study conducted in the Netherlands published in 2020 did find an association in participants aged more than 18 years, for which a possible explanation could be that exposure to pornography from early adolescence could result in an earlier sexual debut and, eventually, the emergence of the association between exposure to pornography and unprotected sex in late adolescence.27,28

- •

Problematic sexual behavior: this construct refers to sexual behaviors involving aggression or coercion, between children of different ages, without consent or that does not respond to adult/caregiver intervention.28 A meta-analysis published in 2023 revealed that minors exposed to sexual content were 2.5 times more likely to exhibit problematic sexual behavior.28

- •

Sexual permissiveness: understood as engaging in sexual activity without emotional engagement and with multiple partners. In adolescents, the use of pornography is associated with more sexually permissive attitudes.19,29,30

- •

Electronic coercion and sexting: A study conducted in adolescents in Spain found that those who reported greater use of pornography were more likely to engage in sexting. The more explicit the images, the higher the risks associated with their subsequent sharing without permission and that they be eventually used as a means for coercion, blackmail or humiliation online, a phenomenon known as “revenge porn”.31

- •

Sexual violence: the association with exposure to pornography has not been clearly established when only these two variables are considered,32 but there is evidence of a significant association between them in combination with other factors, such as aggressiveness, lack of empathy and criminal behavior.23,31,32

Autonomy is understood as the capacity for self-government and making responsible decisions about one’s life. It is not a static construct, but a dynamic process that emerges as the individual develops, fostered by the immediate environment, and involves the recognition, gradual and in each specific context, of the ability to make decisions independently.

The age of consent, far from marking the actual boundary between having or not having the maturity to engage in different types of relationships, is a consensus established by legislators that does not recognize the fact that different skills involved in decision-making take different amounts of time to develop, so that adolescents can be considered mature in some respects and immature in others.

The skills associated with mental processes employed in situations calling for deliberation in the absence of time pressure or high levels of emotion (logic problems, consent to participation in research or medical decisions), known as “cold cognition”, develop earlier compared to mental processes in affectively charged situations in which deliberation is unlikely or rushed, known as “hot cognition”.33

Thus, we may assume the existence of a “maturity gap” that may be misleading, that is, it may be possible to erroneously assume that an adolescent who has certain cognitive skills has the capacity to make decisions in situations that are emotionally charged or in which there is peer pressure, as is the case of sexual relations.33

The concept of autonomy, understood as the ability to act independently and consistently with one’s own values and beliefs, rests on the assumption that the individual acts freely and is not conditioned by external factors. As individuals, we are integrated in a network of relationships with other human beings within a specific cultural context. The model of relational autonomy highlights the role of the social context, interpersonal relationships and emotional aspects in the decision-making process of individuals.34 Perceptions are shaped and validated by the environment surrounding the individual, so that factors such as membership in specific groups, current trends, previous history, the culture in which the individual was raised, stereotypes and the self all influence decision-making.34,35

From a personal perspective, the notion of sexual consent is founded on two concepts: desire and willingness. Willingness should always take precedence over desire, but willingness does not always entail desire, and consent is only given freely, strictly speaking, when the individual desires to engage in the relations, for willingness can result from giving in to pressure coming from the immediate environment or peers, social norms or trends, or pressure the partner, for instance, out of fear of abandonment or a need for affection or recognition.35

From an ethical standpoint, consent cannot justify certain behaviors nor does it legitimize all behavior, “no one can validly consent to being harmed in a manner contrary to the dignity of human beings”, which would be tantamount to renouncing dignity, an inalienable right.35

Our acts of communication build a shared reality, and communication encompasses not only verbal language, what is verbalized, but the context around it. Acts motivated by the intention of the speaker, and not by the outcome, imply an absence of coercion, a search for consensus. In pornography, acts focus on the outcome, there is barely any communication, there is no consensus, only the resulting action is pursued, even if it is by means of violence.35

ConclusionSexuality develops parallel to personality, and as such, merits guidance and education from childhood. At present, Spain allows but does not guarantee emotional and sexuality education.

To educate is to foster freedom and critical thinking in the individual, the capacity to make decisions based on reflection and weighing their consequences, resisting the influence of trends and external pressures. It is important to understand that silence also is a form of education, as treating sexuality as taboo leaves adolescents without guidance and exposes them to pornography as a major resource for learning about sex.

Although a majority of adolescents are or have been exposed to pornography, there are certain profiles associated with an increased risk of problematic use, although it is unclear whether the observed negative outcomes can be attributed solely to the use of pornography or the features that define the high-risk profile are what actually makes the use problematic.

Adolescents that habitually use pornography are at risk of developing a sexual script based on inequality and humiliation, unprotected sexual intercourse, online bullying and sexual violence.

Porn literacy is an educational strategy in which adolescents are encouraged to analyze the sexual practices seen in digital media, thus empowering critical thinking regarding pornography. Prohibition, as opposed to taking advantage of the exposure to open up a discussion in the family or the classroom, will simply perpetuate the risks associated with the use of pornography.

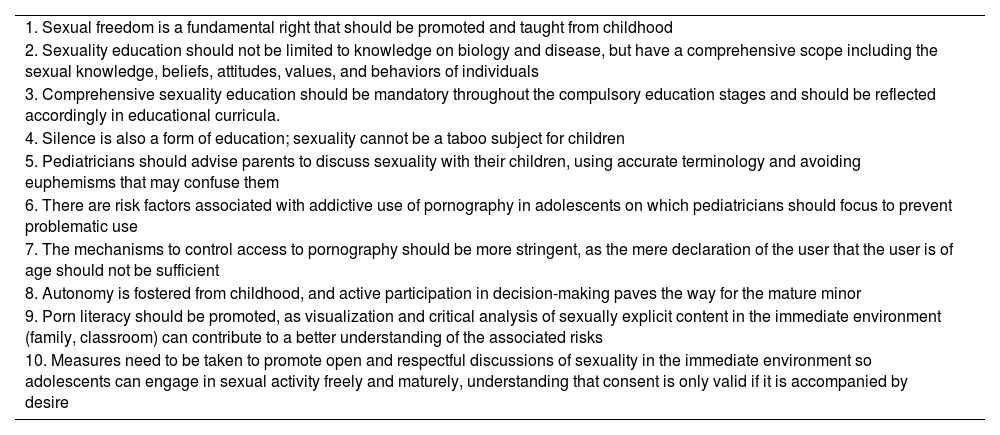

We summarized the main aspects of sexual consent identified in the literature review into “ten principles” (Table 5) as well as with practical recommendations that can be applied in everyday pediatric clinical practice.

The ten principles of sexual consent. Proposed interventions.

| 1. Sexual freedom is a fundamental right that should be promoted and taught from childhood |

| 2. Sexuality education should not be limited to knowledge on biology and disease, but have a comprehensive scope including the sexual knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors of individuals |

| 3. Comprehensive sexuality education should be mandatory throughout the compulsory education stages and should be reflected accordingly in educational curricula. |

| 4. Silence is also a form of education; sexuality cannot be a taboo subject for children |

| 5. Pediatricians should advise parents to discuss sexuality with their children, using accurate terminology and avoiding euphemisms that may confuse them |

| 6. There are risk factors associated with addictive use of pornography in adolescents on which pediatricians should focus to prevent problematic use |

| 7. The mechanisms to control access to pornography should be more stringent, as the mere declaration of the user that the user is of age should not be sufficient |

| 8. Autonomy is fostered from childhood, and active participation in decision-making paves the way for the mature minor |

| 9. Porn literacy should be promoted, as visualization and critical analysis of sexually explicit content in the immediate environment (family, classroom) can contribute to a better understanding of the associated risks |

| 10. Measures need to be taken to promote open and respectful discussions of sexuality in the immediate environment so adolescents can engage in sexual activity freely and maturely, understanding that consent is only valid if it is accompanied by desire |

There were no external sources of funding for this article or the preceding research, and the study has not been presented at any meeting, congress or conference.