Epidemics of pertussis or whooping cough, known from the VII century as the “100-day cough”, were documented in the XVI and XVII centuries in Europe and Asia. In 1906, Bordet identified the causative pathogen, which allowed the development of an effective vaccine that has since been perfected to reduce its reactogenicity.1

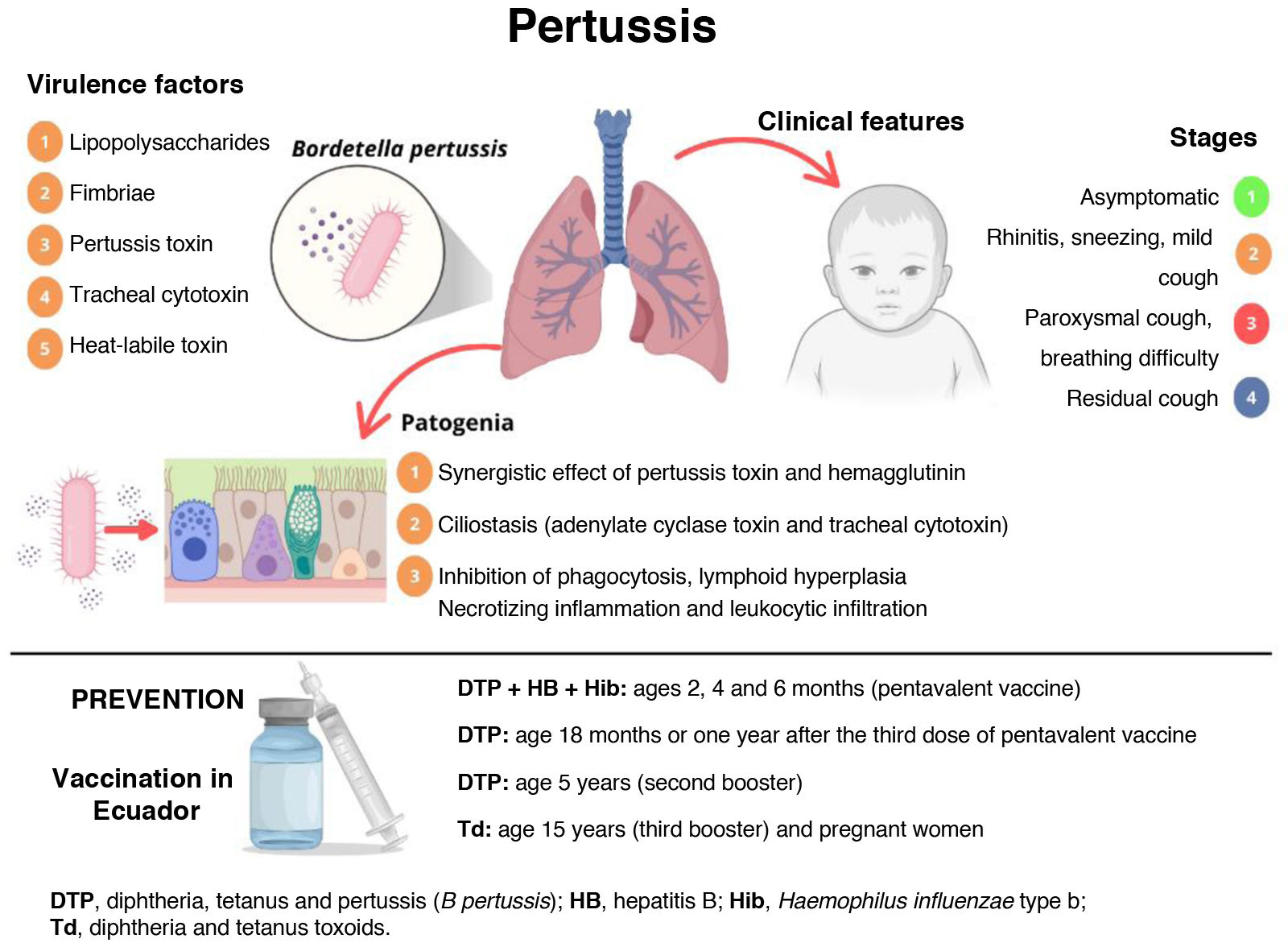

Bordetella pertussis is a gram-negative, encapsulated, aerobic non-spore forming coccobacillus in the same genus as Bordetella parapertussis, which causes pertussis-like syndrome. It has several virulence factors, including the pertussis toxin, which causes hemagglutination and affects T cells. The combination of heat-labile toxin, tracheal cytotoxin and liposaccharide causes tissue damage in the respiratory tract. It is equipped with fimbriae and agglutinogens that allow bacterial aggregation as well as outer membrane proteins such as OMP 15, OMP 18 or OMP 19 for protection within the host (Fig. 1).

Recent outbreaks in the United States, Mexico, Brazil and Peru are indicative of a reduction in herd immunity in association with factors such as low vaccination coverage following the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this letter is to emphasize the need to reinforce prevention efforts, epidemiological surveillance and immunization strategies against this microorganism and other pathogens with a higher basic reproduction number (R0), which may be even more lethal in the pediatric population, as explained by Piñeiro Pérez in the editorial “I’m gonna make him a vaccine he can’t refuse.”2

Before the pandemic, approximately 170000 new cases of disease associated with B. pertussis were notified each year worldwide, but in 2024 outbreaks were reported in Asia and Europe; with more than 300000 cases reported in the first semester in China, doubling the global prevalence to date.3

In the case of Ecuador, an outbreak that added up to 1768 cases by epidemiological week 24 has been reported in 2025, with a higher incidence of disease and of severe complications in infants under one year, including several fatalities in this age group, thus exceeding the figures recorded to date in the country since 2002.4

In response to the situation, the Ministry of Public Health has issued an epidemiological alert, prioritizing the vaccination of children aged less than 7 years as a key objective and monitoring adherence to the five-dose vaccination schedule that should be administered by this age: three doses by age 6 months (primary series), first booster dose at age 18 months and second booster dose at age 5 years.4

Another relevant factor is the reduced effectiveness of vaccination on account of the use of acellular vaccines, with evidence of waning vaccine-derived immunity within five or six years. In addition, genetic changes in B. pertussis have contributed to a reduction in the effectiveness of current vaccines and to the development of macrolide resistance.1

Still, vaccination in Ecuador is insufficient, partly on account of the missed doses and spike in cases during the pandemic, but, unfortunately, also due to the increase in anti-vaccine groups in the population of the country,2 which has motivated us to publish this letter underscoring the resurgence of infectious diseases that should have been eradicated through the systematic vaccination of the population.