Floods constitute one of the most widely described natural phenomena worldwide, and their frequency is increasing due to the consequences of climate change. Floods pose risks to the affected populations, including an increase in communicable diseases mainly due to population displacement and overcrowding, deficiencies in hygiene and dietary measures and difficulties accessing health care. The most frequently reported infectious diseases in the context of these disasters are gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases and diseases resulting from wound infection. Epidemic outbreaks of infections such as leptospirosis or vector-borne diseases, which are usually less prevalent but whose increased incidence is closely related to this type of disasters, have also been described.

These events evince the need to develop epidemiological surveillance protocols and for scientific societies to establish consensus-based guidelines for the diagnosis and therapeutic management of the most prevalent communicable diseases.

This consensus document was developed by the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP) in collaboration with the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP) and the Sociedad Valenciana de Pediatría (SVP) to establish recommendations for the therapeutic management of the main infectious diseases that may affect children impacted by floods, which could also be applicable to other natural disasters.

Las inundaciones son uno de los fenómenos naturales más descritos a nivel mundial cuya incidencia va en aumento debido a las consecuencias producidas por el cambio climático. La aparición de estos desastres conlleva riesgos en la población afectada incluyendo el aumento de enfermedades transmisibles derivado principalmente del desplazamiento y hacinamiento de la población, la deficiencia de medidas higiénico dietéticas y la dificultad de acceso a servicios socio sanitarios. Las enfermedades infecciosas más frecuentemente descritas en estas catástrofes son las gastrointestinales, respiratorias y aquellas producidas por la sobreinfección de heridas. También se ha descrito brotes epidémicos por infecciones menos prevalentes como la leptospirosis o infecciones transmitidas por vectores cuyo aumento de incidencia ha sido fuertemente relacionado con este tipo de desastres.

Ante estos eventos es primordial el desarrollo de protocolos de vigilancia epidemiológica, así como, la elaboración de consensos de diagnóstico y manejo terapéutico de las enfermedades transmisibles más prevalentes por parte de las sociedades científicas.

Este documento de consenso ha sido elaborado por la Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP) en colaboración con la Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP) y la Sociedad Valenciana de Pediatría (SVP) con la finalidad de establecer recomendaciones para el manejo terapéutico de las principales enfermedades infecciosas que puedan producirse en los niños afectados por inundaciones, pudiendo ser extensible a otras catástrofes naturales.

Since the middle of 2022, floods have been the most frequent natural disasters worldwide, resulting in both deaths and high economic costs. Melting polar ice and rising sea levels, attributed to climate change, are among the factors responsible for the increase in extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, monsoons, tsunamis and hurricanes.1 This increase is particularly evident in areas such as Australia, North America, central and southeastern Europe, Africa and Southeast Asia.2

The communicable diseases most commonly reported after natural disasters, such as floods, result from various factors that occur abruptly and put especially vulnerable groups at risk, including pediatric patients. Outbreaks develop due to the displacement of the affected population, forced to seek shelter in camps or buildings with poor ventilation, leading to overcrowded conditions and, as a result, an increase in respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. The problem is compounded by the disruption of services that fulfil basic needs, such as clean water or food and, consequently, poor hygiene in affected individuals, in addition to the predisposition of certain groups, such as children with incomplete vaccination or immunocompromised status, or chronically ill patients whose ongoing treatment is interrupted, combined with a lack or reduced access to health care services.3,4

Following the recent floods in Spain caused by the “cold drop” or isolated high-altitude depression, commonly referred to as the DANA, which chiefly affected the Valencian Community, the Sociedad Española de Infectología Pediátrica (SEIP, Spanish Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases), in collaboration with the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) and the Sociedad Valenciana de Pediatría (SVP, Valencian Society of Pediatrics) developed the present document to provide recommendations for the management of pediatric patients with infectious diseases related to flooding. Due to the limited evidence on the antimicrobial treatment of some infections in the pediatric population, the proposed guidelines are based on the epidemiology described in the literature and the opinion of the authors, with the hope that they may be helpful to guide the initial management of these infections.

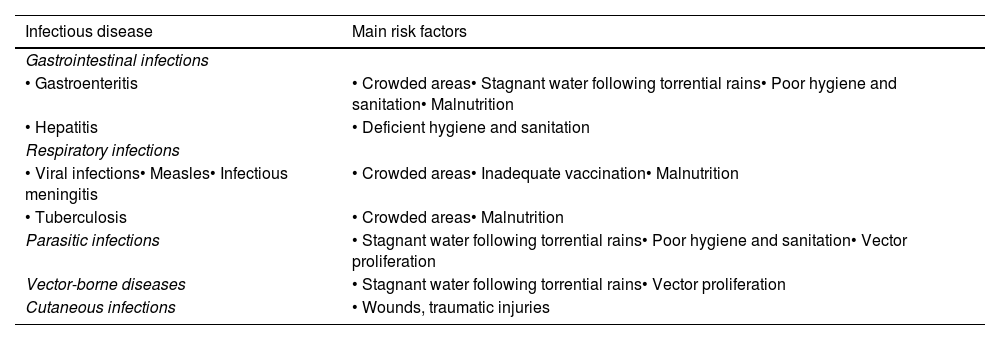

Infectious diseases related to floodingIn the event of flooding or other natural disasters, the emergence of infections is associated with specific risk factors (Table 1) and tends to follow a timeline determined by the phases of the disaster.3,5,6

Main communicable diseases described after floods and their association with risk factors.

| Infectious disease | Main risk factors |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal infections | |

| • Gastroenteritis | • Crowded areas• Stagnant water following torrential rains• Poor hygiene and sanitation• Malnutrition |

| • Hepatitis | • Deficient hygiene and sanitation |

| Respiratory infections | |

| • Viral infections• Measles• Infectious meningitis | • Crowded areas• Inadequate vaccination• Malnutrition |

| • Tuberculosis | • Crowded areas• Malnutrition |

| Parasitic infections | • Stagnant water following torrential rains• Poor hygiene and sanitation• Vector proliferation |

| Vector-borne diseases | • Stagnant water following torrential rains• Vector proliferation |

| Cutaneous infections | • Wounds, traumatic injuries |

In the initial or impact phase, corresponding to the first four days, outbreaks are infrequent, and a majority of the infections that occur involve wounds, burns or fractures. In the case of flooding, pneumonia due to aspiration of contaminated water is also common.

In the four weeks that follow, the post-impact phase, emerging infections usually result from the contamination of water and food and can give rise to outbreaks due to overcrowded conditions in the displaced population. Seasonal viral infections are also frequent in this phase.

Last of all, the recovery phase, which takes place approximately one month after the event, is the time when infections with long incubation periods, like leptospirosis, and vector-transmitted diseases tend to be diagnosed.

We proceed to describe the etiology, microbiological diagnosis and treatment of the communicable diseases most commonly described in the context of flooding.

Gastrointestinal infectionsGastrointestinal infections are a common phenomenon in the wake of natural disasters. Floods cause disruptions in sewage systems and clean water supplies that may result in contamination of water sources, which, together with the limitation of hygiene measures, favors the emergence of diseases transmitted by contaminated water or food. These infections usually appear in the first few weeks from the disaster, exacerbating morbidity in vulnerable populations, especially in areas with compromised sanitation systems and limited access to drinking water.

The main etiological agents include enteropathogenic bacteria such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Aeromonas spp. and Vibrio cholerae. Enteric viruses, such as rotavirus or norovirus, are also frequent in this context, along with parasitic protozoa such as Giardia intestinalis or Cryptosporidium spp.6,7

The symptoms vary depending on the etiological agent and commonly include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever and, in severe cases, dehydration and electrolyte disturbances that can be life-threatening. The diagnosis is clinical, with etiological confirmation by microbiological tests such as stool cultures, stool parasite analysis, rapid tests for the detection of bacterial toxins, viral and parasitic antigens, and molecular tests (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]).

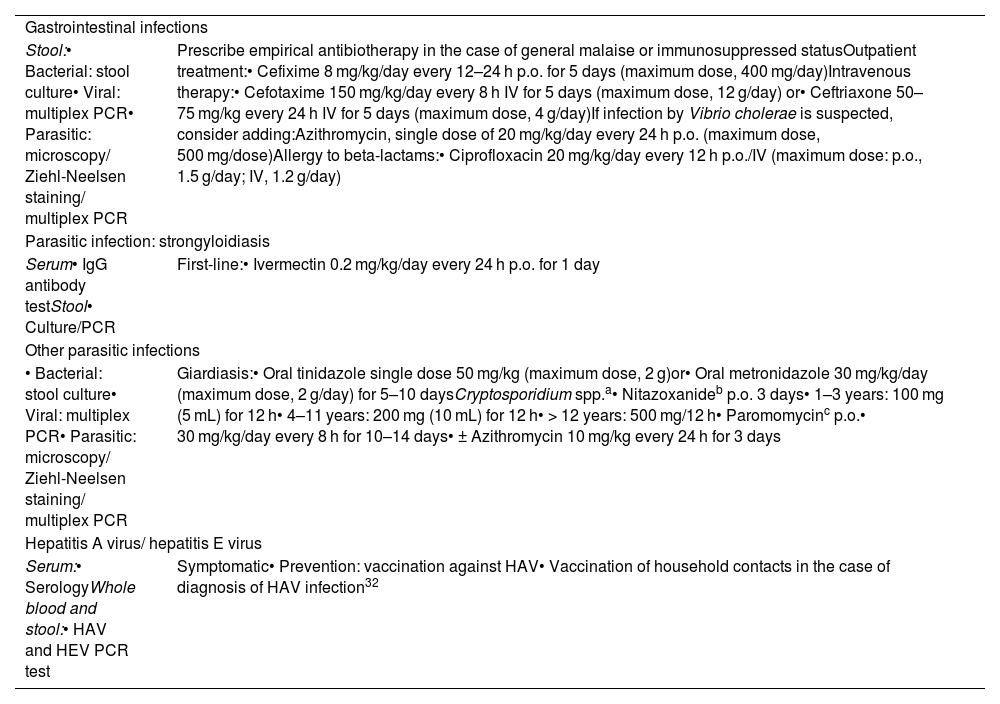

Rehydration therapy is key and can be delivered orally with administration of rehydration solutions or intravenously in cases of severe dehydration. Some cases may require prescription of antibiotherapy based on the course of disease or etiological suspicion (Table 2).

Gastrointestinal infections. Recommendations for microbiological diagnosis and treatment.

| Gastrointestinal infections | |

| Stool:• Bacterial: stool culture• Viral: multiplex PCR• Parasitic: microscopy/ Ziehl-Neelsen staining/ multiplex PCR | Prescribe empirical antibiotherapy in the case of general malaise or immunosuppressed statusOutpatient treatment:• Cefixime 8 mg/kg/day every 12–24 h p.o. for 5 days (maximum dose, 400 mg/day)Intravenous therapy:• Cefotaxime 150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV for 5 days (maximum dose, 12 g/day) or• Ceftriaxone 50–75 mg/kg every 24 h IV for 5 days (maximum dose, 4 g/day)If infection by Vibrio cholerae is suspected, consider adding:Azithromycin, single dose of 20 mg/kg/day every 24 h p.o. (maximum dose, 500 mg/dose)Allergy to beta-lactams:• Ciprofloxacin 20 mg/kg/day every 12 h p.o./IV (maximum dose: p.o., 1.5 g/day; IV, 1.2 g/day) |

| Parasitic infection: strongyloidiasis | |

| Serum• IgG antibody testStool• Culture/PCR | First-line:• Ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg/day every 24 h p.o. for 1 day |

| Other parasitic infections | |

| • Bacterial: stool culture• Viral: multiplex PCR• Parasitic: microscopy/ Ziehl-Neelsen staining/ multiplex PCR | Giardiasis:• Oral tinidazole single dose 50 mg/kg (maximum dose, 2 g)or• Oral metronidazole 30 mg/kg/day (maximum dose, 2 g/day) for 5–10 daysCryptosporidium spp.a• Nitazoxanideb p.o. 3 days• 1–3 years: 100 mg (5 mL) for 12 h• 4–11 years: 200 mg (10 mL) for 12 h• > 12 years: 500 mg/12 h• Paromomycinc p.o.• 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h for 10–14 days• ± Azithromycin 10 mg/kg every 24 h for 3 days |

| Hepatitis A virus/ hepatitis E virus | |

| Serum:• SerologyWhole blood and stool:• HAV and HEV PCR test | Symptomatic• Prevention: vaccination against HAV• Vaccination of household contacts in the case of diagnosis of HAV infection32 |

Abbreviations: HAV, hepatitis A virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; IV, intravenous route; p.o., oral route.

In endemic areas, outbreaks of hepatitis A and hepatitis E virus infection can also occur as a result of the contamination of the drinking water supply.6 The most frequent symptoms of these infections are gastrointestinal, followed by jaundice and acholia.8

Parasitic infections: strongyloidiasisParasitic diseases are chiefly caused by helminths of the Strongyloides stercoralis species.

Although it generally occurs in subtropical and tropical countries, transmission is also possible in countries with a temperate climate. In Spain, several autochthonous cases have been reported, the majority in the province of Valencia.9

The most frequent route of transmission is percutaneous infection through skin contact with filariform larvae present in soil or other surfaces contaminated with human feces. Less frequently, infection occurs through the ingestion of contaminated water or food. All of these circumstances are facilitated by the breakdown of hygiene and sanitation measures following natural disaster.10

The clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic or subclinical to severe forms of hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated strongyloidiasis, which can be fatal in immunocompromised children.

Acute strongyloidiasis usually manifests as a localized pruritic, erythematous rash with a serpiginous appearance that reflects the subcutaneous migration of the larvae. Due to its characteristic life cycle, the parasite may reach the lungs, giving rise to cough and dyspnea, or the gastrointestinal tract, about three to four weeks after infection, causing abdominal pain and diarrhea.

Chronic strongyloidiasis can persist for years due to cycles of autoinfection. It usually goes undetected and, when symptomatic, involves the skin or the gastrointestinal tract, with abdominal pain and diarrhea alternating with constipation. Respiratory manifestations are rare, although severe infection can cause Löffler syndrome, characterized by cough, wheezing and eosinophilia.11

The diagnosis is based on the detection of larvae in stool through direct microscopy or molecular tests and fecal culture. Serologic tests, which offer a high sensitivity (85%) and specificity (97%), are the gold standard of diagnosis in oligosymptomatic and chronic infection cases.11 Blood tests usually reveal eosinophilia and IgE eleveation.1,7 At present, ivermectin is the first-line treatment.

Table 2 summarizes the therapeutic approach for other diseases whose incidence may increase after flooding.

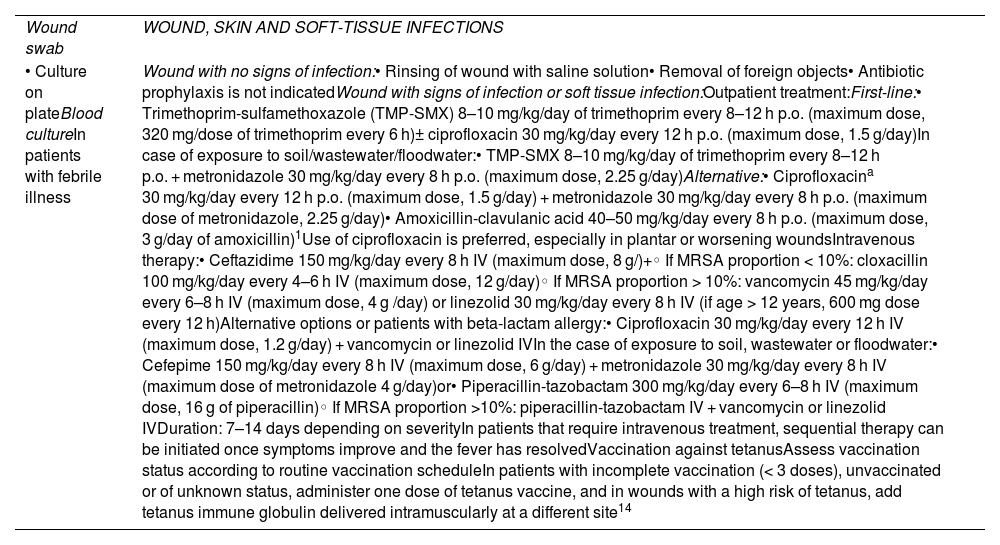

Skin and soft tissue infectionsSkin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are common in the impact phase or first few days after a hydrological disaster, although they may develop at any point in the first three weeks following the disaster. They result from the infection of traumatic wound and skin problems associated with water exposure. They can range from superficial infections like cellulitis to deeper infections such as fasciitis, necrotizing myositis or even osteoarticular infections.

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are the agents typically involved in these infections.12 However, evidence from several studies shows that gram-negative bacteria play an important role in SSTIs following hydrological events. Among them, bacteria from the Aeromonas genus, which dwell in both fresh and salt water, can cause uncomplicated cellulitis or extend deeper, resulting in necrotizing soft tissue infections.

Polymicrobial infections, involving other gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, have also been common among survivors of tsunamis and floods. In general, in patients presenting with a SSTI following immersion in contaminated water, clinicians should suspect a polymicrobial etiology or gram-negative bacilli involvement.

Cutaneous infections with a late onset and those that do not improve with conventional antibiotherapy regimens should increase suspicion of an uncommon microbial agent. Some case series have reported cases of infection by Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis), nontuberculous mycobacteria (M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae) and filamentous fungi (Aspergillus spp., Mucor spp.).4,12

The diagnosis is essentially clinical. In the case of purulent wounds or wounds requiring surgical drainage, we recommend submitting a sample for culture.

The initial management involves adequate wound cleaning and the removal of foreign bodies, if present.13

Correct vaccination against tetanus should be verified and, in the case of unknown or unvaccinated/incomplete vaccination status, a dose of Td administered, and, depending on the type of wound, administration of tetanus immune globulin as well.14

In the case of necrosis or abscess formation, the treatment consists of rapid surgical debridement and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Empirical antibiotherapy should offer broad coverage of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria while awaiting the results of wound culture (Table 3).13

Skin and soft tissue infections. Recommendations on microbiological diagnosis and empirical treatment.

| Wound swab | WOUND, SKIN AND SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS |

| • Culture on plateBlood cultureIn patients with febrile illness | Wound with no signs of infection:• Rinsing of wound with saline solution• Removal of foreign objects• Antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicatedWound with signs of infection or soft tissue infection:Outpatient treatment:First-line:• Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 8–10 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim every 8–12 h p.o. (maximum dose, 320 mg/dose of trimethoprim every 6 h)± ciprofloxacin 30 mg/kg/day every 12 h p.o. (maximum dose, 1.5 g/day)In case of exposure to soil/wastewater/floodwater:• TMP-SMX 8–10 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim every 8–12 h p.o. + metronidazole 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h p.o. (maximum dose, 2.25 g/day)Alternative:• Ciprofloxacina 30 mg/kg/day every 12 h p.o. (maximum dose, 1.5 g/day) + metronidazole 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h p.o. (maximum dose of metronidazole, 2.25 g/day)• Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 40–50 mg/kg/day every 8 h p.o. (maximum dose, 3 g/day of amoxicillin)1Use of ciprofloxacin is preferred, especially in plantar or worsening woundsIntravenous therapy:• Ceftazidime 150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose, 8 g/)+◦ If MRSA proportion < 10%: cloxacillin 100 mg/kg/day every 4–6 h IV (maximum dose, 12 g/day)◦ If MRSA proportion > 10%: vancomycin 45 mg/kg/day every 6–8 h IV (maximum dose, 4 g /day) or linezolid 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (if age > 12 years, 600 mg dose every 12 h)Alternative options or patients with beta-lactam allergy:• Ciprofloxacin 30 mg/kg/day every 12 h IV (maximum dose, 1.2 g/day) + vancomycin or linezolid IVIn the case of exposure to soil, wastewater or floodwater:• Cefepime 150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose, 6 g/day) + metronidazole 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose of metronidazole 4 g/day)or• Piperacillin-tazobactam 300 mg/kg/day every 6–8 h IV (maximum dose, 16 g of piperacillin)◦ If MRSA proportion >10%: piperacillin-tazobactam IV + vancomycin or linezolid IVDuration: 7–14 days depending on severityIn patients that require intravenous treatment, sequential therapy can be initiated once symptoms improve and the fever has resolvedVaccination against tetanusAssess vaccination status according to routine vaccination scheduleIn patients with incomplete vaccination (< 3 doses), unvaccinated or of unknown status, administer one dose of tetanus vaccine, and in wounds with a high risk of tetanus, add tetanus immune globulin delivered intramuscularly at a different site14 |

Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; IV, intravenous route; p.o., oral route.

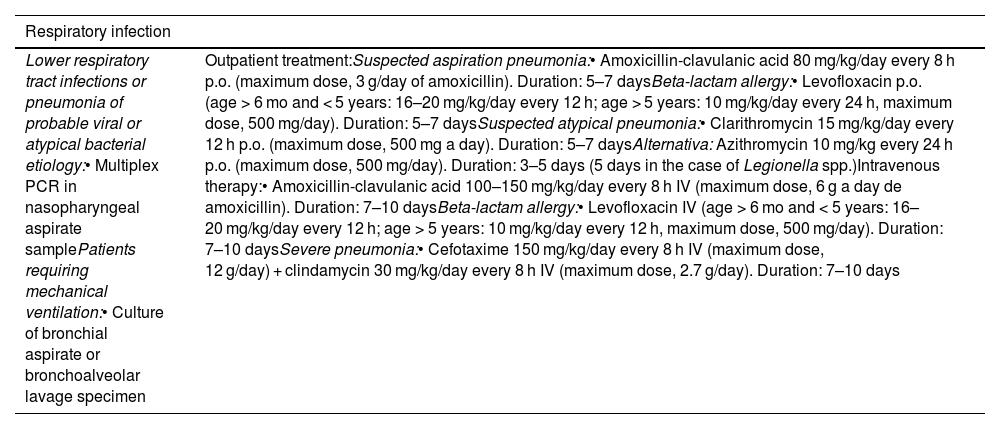

They are one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children under 5 years following a natural disaster. The destruction of homes and overcrowded conditions promote the spread of respiratory viruses. In addition, immersion in or aspiration of contaminated floodwater can result in lower respiratory tract infection.6,12

Seasonal viruses (influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, SARS-CoV-2) are the most frequently involved respiratory pathogens in children staying in camps or shelters. Bacterial infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis, especially in unvaccinated children, and outbreaks by bacteria causing atypical pneumonia, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Legionella spp., have also been described.3

In the case of pneumonia associated with immersion, the etiology is usually polymicrobial and usually involves organisms of the oropharyngeal flora, S. pneumoniae and anaerobic bacteria, and the disease may be complicated by the development of abscesses, empyema or pulmonary necrosis.6,12

The diagnosis is based on the clinical manifestations, although a chest radiograph may be performed in the case of suspected bacterial or aspiration pneumonia. The method recommended for microbiological diagnosis is multiplex PCR in a nasopharyngeal aspirate sample, using a panel that includes atypical viruses and bacteria. In the case of severe pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation, order culture and molecular testing (multiplex PCR pneumonia panel) in lower respiratory tract specimens (bronchial aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage).

The treatment of viral respiratory infections is symptomatic. The first-line treatment in cases of suspected immersion-associated or aspiration pneumonia is amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Table 4).

Respiratory infections. Recommendations on microbiological diagnosis and empirical treatment.

| Respiratory infection | |

|---|---|

| Lower respiratory tract infections or pneumonia of probable viral or atypical bacterial etiology:• Multiplex PCR in nasopharyngeal aspirate samplePatients requiring mechanical ventilation:• Culture of bronchial aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage specimen | Outpatient treatment:Suspected aspiration pneumonia:• Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 80 mg/kg/day every 8 h p.o. (maximum dose, 3 g/day of amoxicillin). Duration: 5–7 daysBeta-lactam allergy:• Levofloxacin p.o. (age > 6 mo and < 5 years: 16–20 mg/kg/day every 12 h; age > 5 years: 10 mg/kg/day every 24 h, maximum dose, 500 mg/day). Duration: 5–7 daysSuspected atypical pneumonia:• Clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day every 12 h p.o. (maximum dose, 500 mg a day). Duration: 5–7 daysAlternativa: Azithromycin 10 mg/kg every 24 h p.o. (maximum dose, 500 mg/day). Duration: 3–5 days (5 days in the case of Legionella spp.)Intravenous therapy:• Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 100–150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose, 6 g a day de amoxicillin). Duration: 7–10 daysBeta-lactam allergy:• Levofloxacin IV (age > 6 mo and < 5 years: 16–20 mg/kg/day every 12 h; age > 5 years: 10 mg/kg/day every 12 h, maximum dose, 500 mg/day). Duration: 7–10 daysSevere pneumonia:• Cefotaxime 150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose, 12 g/day) + clindamycin 30 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV (maximum dose, 2.7 g/day). Duration: 7–10 days |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous route; p.o., oral route.

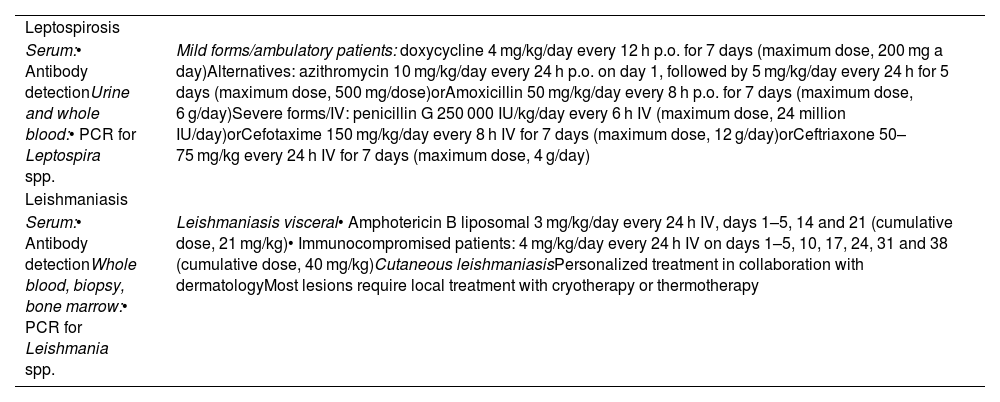

Increases in the incidence of zoonotic diseases have been described in the context of floods and other catastrophes as a consequence of disruptions of hygienic-sanitary measures and increased contact with animals.

Leptospirosis is one of the zoonoses most strongly associated with extreme weather events. Studies conducted in the Philippines and Fiji found significant increases in the diagnosis of leptospirosis following torrential rains.15,16 A recent meta-analysis found a high risk of leptospirosis following flooding (OR, 2.19).17

The disease is caused by spirochetes of the Leptospira genus (chiefly L. interrogans), and rodents are the main reservoirs involved in human disease. Leptospires reproduce in the renal tubules of rodents and are shed in urine, after which infection occurs through the contact of nonintact skin or mucous membranes with infected rodents or contaminated water, food or surfaces.4 It is widely distributed worldwide and, based on data from the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network of Spain (RENAVE), in 2022 there were 50 reported cases of leptospirosis in the country.18

The incubation period of leptospirosis is long, of up to 20 days, and its presentation varies, ranging from subclinical manifestations to severe disease with multiple organ failure.

Most patients develop mild flu-like illness, with fever, myalgia, vomiting and headache, especially in the frontal region, and conjunctival suffusion and jaundice are also common. These manifestations correspond to the septicemic phase of infection. However, some patients develop severe disease secondary to severe inflammation and altered and ineffective host responses. Myocarditis, liver, renal and respiratory failure, meningitis and coagulopathy are the most commonly described manifestations in severe cases.19,20

The microbiological diagnosis is obtained by serology (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], immunochromatographic assay or microscopic agglutination test) or molecular tests in blood, cerebrospinal fluid or urine specimens. Polymerase chain reaction tests in blood samples offer a high sensitivity the week of symptom onset, with variable sensitivity in urine due to the intermittent shedding of the bacteria. Culture and microscopy can also be used for diagnosis, but require experienced staff and special resources, so they are rarely used today.21 In general, we recommend performance of PCR in a blood sample in the first 10 days from onset or in urine, and serology from 7 days after onset.

Penicillin is the treatment of choice for patients requiring parenteral treatment. In mild cases, oral doxycycline is the first-line treatment, independently of age22 (Table 5).

Zoonotic diseases. Recommendations for microbiological diagnosis and antibiotherapy.

| Leptospirosis | |

| Serum:• Antibody detectionUrine and whole blood:• PCR for Leptospira spp. | Mild forms/ambulatory patients: doxycycline 4 mg/kg/day every 12 h p.o. for 7 days (maximum dose, 200 mg a day)Alternatives: azithromycin 10 mg/kg/day every 24 h p.o. on day 1, followed by 5 mg/kg/day every 24 h for 5 days (maximum dose, 500 mg/dose)orAmoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day every 8 h p.o. for 7 days (maximum dose, 6 g/day)Severe forms/IV: penicillin G 250 000 IU/kg/day every 6 h IV (maximum dose, 24 million IU/day)orCefotaxime 150 mg/kg/day every 8 h IV for 7 days (maximum dose, 12 g/day)orCeftriaxone 50–75 mg/kg every 24 h IV for 7 days (maximum dose, 4 g/day) |

| Leishmaniasis | |

| Serum:• Antibody detectionWhole blood, biopsy, bone marrow:• PCR for Leishmania spp. | Leishmaniasis visceral• Amphotericin B liposomal 3 mg/kg/day every 24 h IV, days 1–5, 14 and 21 (cumulative dose, 21 mg/kg)• Immunocompromised patients: 4 mg/kg/day every 24 h IV on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31 and 38 (cumulative dose, 40 mg/kg)Cutaneous leishmaniasisPersonalized treatment in collaboration with dermatologyMost lesions require local treatment with cryotherapy or thermotherapy |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous route; p.o., oral route.

An increase in animal bites by pets has also been described in relation to flooding. Pasteurella multocida, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, staphylococci, streptococci and anaerobic bacteria are present in canine and feline oral flora, so in the case of a bite wound that appears to be infected, the antibiotic of choice is amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.4

Leishmaniasis is endemic in Spain, and the RENAVE reported 387 notified cases in 2023. The incidence was highest in the autonomous communities of Catalonia, Valencian Community and Andalusia.23 An increase in Phlebotomus, a vector of the disease, has been described following flooding, so vector surveillance and control measures should be maximized in the event of a flood.1,24Table 5 describes the microbiological diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis.25

Vector-borne diseasesWhen flooding happens, the incidence of vector-borne diseases tends to increase. At first, floods may devastate the habitats where arthropods, including mosquitoes, reproduce, thus reducing their numbers. However, in the days that follow, stagnant water provides an ideal environment for reproduction.7

Outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases have also been reported in endemic regions, such as malaria, dengue, zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, West Nile fever and Rift Valley fever.1,3,12

Climate change, combined with other environmental and social changes, has contributed to regional shifts in the distribution of mosquitoes that carry specific diseases, such as the Culex or household mosquito, a vector for West Nile virus, and Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus, vectors for dengue, both of which have adapted to new regions and conditions in southern Europe, where outbreaks of these two diseases have been reported with increasing frequency in the past two decades.

Spain has had autochthonous outbreaks of both West Nile virus and dengue.

The wide distribution and the expansion of Aedes albopictus in the Mediterranean region and other areas of Spain entails a moderate risk of local transmission of dengue during the vector activity season (May–November).26,27 The first autochthonous cases were identified in 2018, and cases have been reported in Murcia, Catalonia, Madrid and Ibiza.

The symptoms of dengue tend to be mild and include fever, headache, retroorbital pain, joint and muscle pain, exanthema and bleeding with onset 4 to 7 days after infection. In some cases disease may be severe or progress to dengue hemorrhagic fever, although the probability in Spain is very low, as this condition is typically associated with reinfection by different serotypes in endemic areas.

The diagnosis is based on serology or molecular techniques. Treatment is symptomatic, with administration of paracetamol to control fever and alleviate pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided.28

On the other hand, the presence of West Nile virus in Spain has been documented for two decades. In the 2023 season, there were 19 autochthonous cases reported in humans, with cases reported in the provinces of Cáceres, Huelva, Valencia, Barcelona and Toledo for the first time. In areas where there are clusters of infection during the vector season, there is a moderate risk of transmission, while the risk remains low in the rest of Spain, although the virus is expected to expand to other areas.

Most West Nile virus infections are asymptomatic, and 20% to 40% of infected individuals develop flu-like illness lasting two to five days. Neuroinvasive disease (meningitis, encephalitis and acute flaccid paralysis) occurs in fewer than 1% of cases. The treatment is supportive.29

Both viruses pose a public health challenge and call for an integrated approach combining entomological surveillance, vector control and education of the population.

Vaccine-preventable diseasesOutbreaks of airborne diseases, like measles or meningococcal meningitis, have been described in the context of disasters. In Spain, vaccination coverage rates are high, so the risk is not high at the population level, but it may be high for individuals depending on immune status and proximity to pockets of unvaccinated individuals. It is essential to assess vaccination status in affected individuals, implementing vaccination campaigns and prophylactic measures against meningococcal disease if cases are identified, in addition to isolation and prevention measures if there are cases of measles, as it is highly contagious.

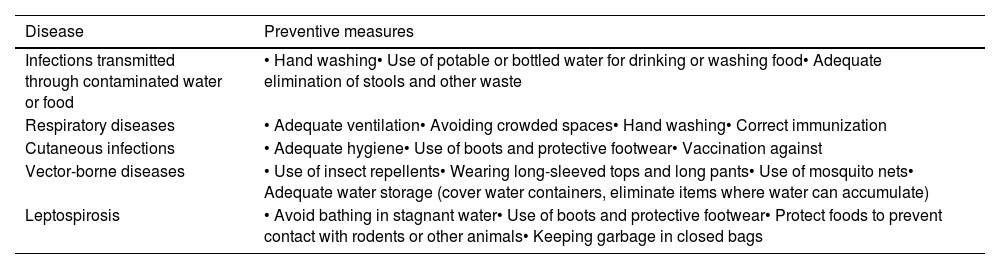

Preventive measures and epidemiological surveillanceThe implementation of preventive measures is essential to avoid the transmission of infectious diseases, mainly by guaranteeing adequate hygiene, ensuring access to clean drinking water and food and enhancing health care delivery in affected areas (Table 6).2,4,30 The emergence of outbreaks should be contained by optimizing vaccination programs in risk areas, preventing the propagation of vectors and implementing epidemiological surveillance protocols.31

General measures for prevention of infectious diseases associated with natural disasters.

| Disease | Preventive measures |

|---|---|

| Infections transmitted through contaminated water or food | • Hand washing• Use of potable or bottled water for drinking or washing food• Adequate elimination of stools and other waste |

| Respiratory diseases | • Adequate ventilation• Avoiding crowded spaces• Hand washing• Correct immunization |

| Cutaneous infections | • Adequate hygiene• Use of boots and protective footwear• Vaccination against |

| Vector-borne diseases | • Use of insect repellents• Wearing long-sleeved tops and long pants• Use of mosquito nets• Adequate water storage (cover water containers, eliminate items where water can accumulate) |

| Leptospirosis | • Avoid bathing in stagnant water• Use of boots and protective footwear• Protect foods to prevent contact with rodents or other animals• Keeping garbage in closed bags |

While all these measures are effective in mitigating the impact of these disasters, the most effective measures are preventive, including disaster preparedness in risk areas and rapid and effective evacuation plans.2

ConclusionHydrological disasters are associated with an increase in communicable diseases, and the pediatric population is among the groups with a high risk. Most of these infections affect displaced people who need to shelter in overcrowded spaces with inadequate hygiene, which favors the spread of infections transmitted through the consumption of contaminated food or water, respiratory infections and zoonotic infections. Awareness and knowledge of the infections that can occur in these disasters and their epidemiological surveillance can ensure and contribute to optimize the appropriate management of these patients.