The impact of skin diseases on quality of life varies widely, and some can have an impact similar to that of asthma or cystic fibrosis.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study with the aim of describing the degree to which quality of life was affected in paediatric patients managed in a dermatology clinic by means of the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).

ResultsIn our study, the skin disease with the greatest impact on quality of life was atopic dermatitis, chiefly on account of symptoms like pruritus and insomnia. It was followed by acne, mainly due to the associated negative feelings (shame, sadness, etc.). Quality of life in patients with viral warts and molluscum contagiosum was mostly affected by the treatment, chiefly based on cryotherapy. Most patients with nevi or café-au-lait spots did not have a decreased quality of life, although up to one third of them had negative feelings in relation to their skin disease.

DiscussionAtopic dermatitis was the common skin disease that caused the greatest impairment in quality of life in our sample, although other diseases also had an impact on different dimensions of quality of life. We ought to underscore the recommendation to use less painful treatments than cryotherapy for viral warts and molluscum contagiosum, as the impairment in quality of life in paediatric patients with these conditions was mainly due to the treatment.

Las enfermedades cutáneas pueden afectar a la calidad de vida de forma muy variable; el impacto de algunas dermatosis puede ser similar al del asma o la fibrosis quística.

Material y métodosRealizamos un estudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal con el objetivo de describir el grado de afectación de la calidad de vida de los niños que acudieron a la consulta monográfica de Dermatología Pediátrica, mediante el Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).

ResultadosEn este estudio la dermatosis con mayor impacto en la calidad de vida fue la dermatitis atópica, debido principalmente a síntomas como el prurito y el insomnio. El segundo grupo diagnóstico con mayor afectación fue el acné, debido principalmente a los sentimientos negativos (vergüenza, tristeza, etc.) asociados al mismo. Los pacientes con verrugas víricas y moluscos contagiosos tuvieron impacto en la calidad de vida debido principalmente al tratamiento de los mismos, que se realizó principalmente con crioterapia. La mayor parte de los pacientes con nevus o manchas café con leche no tuvieron afectación en la calidad de vida, si bien hasta un tercio de ellos tuvieron sentimientos negativos secundarios a su dermatosis.

DiscusiónLa dermatitis atópica fue la enfermedad dermatológica común que más impactó en la calidad de vida en nuestra muestra de pacientes, aunque otros procesos también afectaron a la calidad de vida en distintos aspectos de la misma. Cabe destacar la recomendación de emplear en verrugas víricas y moluscos contagiosos tratamientos más indoloros que la crioterapia, ya que es el tratamiento lo que más impacta en la calidad de vida de los pacientes pediátricos.

Skin diseases affect quality of life to a highly variable degree,1 and some have an impact similar to that of asthma or cystic fibrosis.2 The assessment of the impact of the different skin diseases on quality of life is essential, as it can guide decisions at the clinical level (initiation of biological therapy, modifications to treatment) and at the administrative level (allocating more resources to diseases with a greater impact on quality of life).3,4

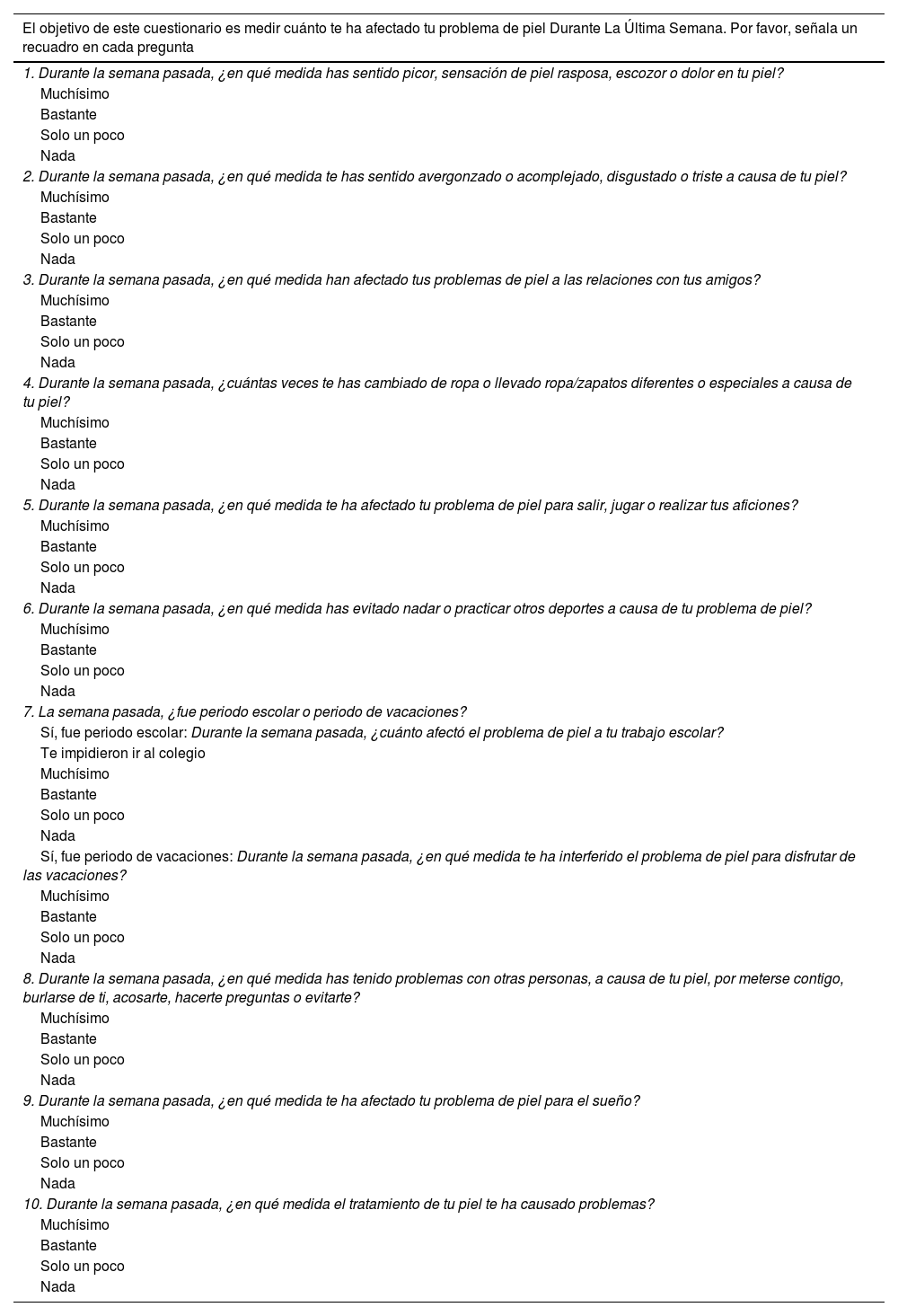

The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) is the instrument used most widely to measure quality of life in children with skin diseases.5 It is a 10-item questionnaire that is easy to complete and validated for use in children aged 4–16 years, and it has been used in several studies, demonstrating its usefulness in the specific impact of skin disease in paediatric patients (Table 1). It evaluates different aspects of skin disease over the previous week: symptoms, feelings like embarrassment, friendship, clothing, playing, sports, academic performance, sleep, interpersonal relationships and impact of treatment. Higher scores indicate greater impairment of quality of life, and the results are interpreted based on the total score (sum of all the item scores).

Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, Spanish version.

| El objetivo de este cuestionario es medir cuánto te ha afectado tu problema de piel Durante La Última Semana. Por favor, señala un recuadro en cada pregunta |

|---|

| 1. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida has sentido picor, sensación de piel rasposa, escozor o dolor en tu piel? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 2. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida te has sentido avergonzado o acomplejado, disgustado o triste a causa de tu piel? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 3. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida han afectado tus problemas de piel a las relaciones con tus amigos? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 4. Durante la semana pasada, ¿cuántas veces te has cambiado de ropa o llevado ropa/zapatos diferentes o especiales a causa de tu piel? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 5. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida te ha afectado tu problema de piel para salir, jugar o realizar tus aficiones? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 6. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida has evitado nadar o practicar otros deportes a causa de tu problema de piel? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 7. La semana pasada, ¿fue periodo escolar o periodo de vacaciones? |

| Sí, fue periodo escolar: Durante la semana pasada, ¿cuánto afectó el problema de piel a tu trabajo escolar? |

| Te impidieron ir al colegio |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| Sí, fue periodo de vacaciones: Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida te ha interferido el problema de piel para disfrutar de las vacaciones? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 8. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida has tenido problemas con otras personas, a causa de tu piel, por meterse contigo, burlarse de ti, acosarte, hacerte preguntas o evitarte? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 9. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida te ha afectado tu problema de piel para el sueño? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

| 10. Durante la semana pasada, ¿en qué medida el tratamiento de tu piel te ha causado problemas? |

| Muchísimo |

| Bastante |

| Solo un poco |

| Nada |

We conducted a study in the department of dermatology of a referral university hospital in Madrid. The primary objective was to describe the degree of the impact of skin disease on the quality of life of children managed at the paediatric dermatology speciality clinic, and the secondary objectives were to analyse potential differences between different diagnostic groups in the degree of impairment of quality of life and in the impact on specific dimensions of quality of life.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study. The study took place between March 2021 and December 2021. We included patients aged 4–16 years who visited the paediatric dermatology clinic and received any of the common diagnoses in this setting: atopic dermatitis (AD), acne, viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, melanocytic nevus or café au lait spots. We excluded patients with severe nondermatological disease that could affect quality of life and patients with dermatological diagnoses other than those noted above.

The instrument used to assess quality of life was the Índice de Calidad de Vida in Dermatología para Niños, which is the validated version of the CDLQI in Spanish6 and has exhibited a high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76–0.88) and a high test-retest reliability (gamma [s] = 0.97; P < 0.001). After taking the history and performing the physical examination of the patient and making the diagnosis, the children completed the questionnaire, administered verbally by the researchers. For the purposes of the descriptive and inferential analyses, we classified patients into 4 diagnostic groups: (1) AD; (2) acne; (3) viral warts and molluscum contagiosum (VW/MC), and (4) skin pigmentation disorders (melanocytic nevus and café au lait spots).

The data were processed and analysed with the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. We have expressed qualitative data as frequency distributions. We summarised quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation (SD). In the case of quantitative variables with a skewed distribution, we used the median and interquartile range (IQR). (RIC). We compared quality of life scores in the different diagnostic groups with the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, as this variable had an asymmetrical distribution, with the Bonferroni correction for the P value. The level of significance was set at 5% for all tests.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our hospital, and we obtained informed consent to the participation of patients in the study.

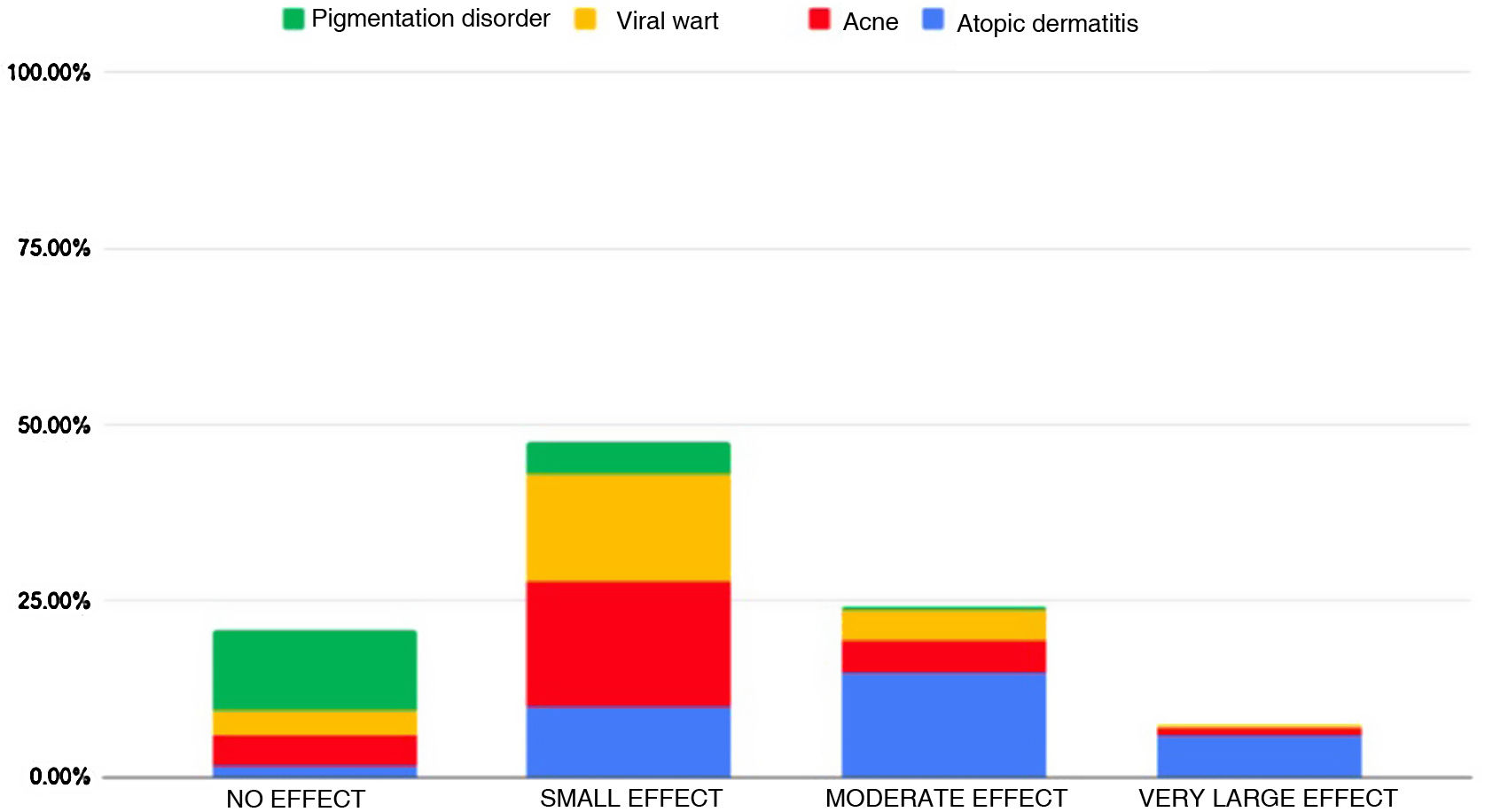

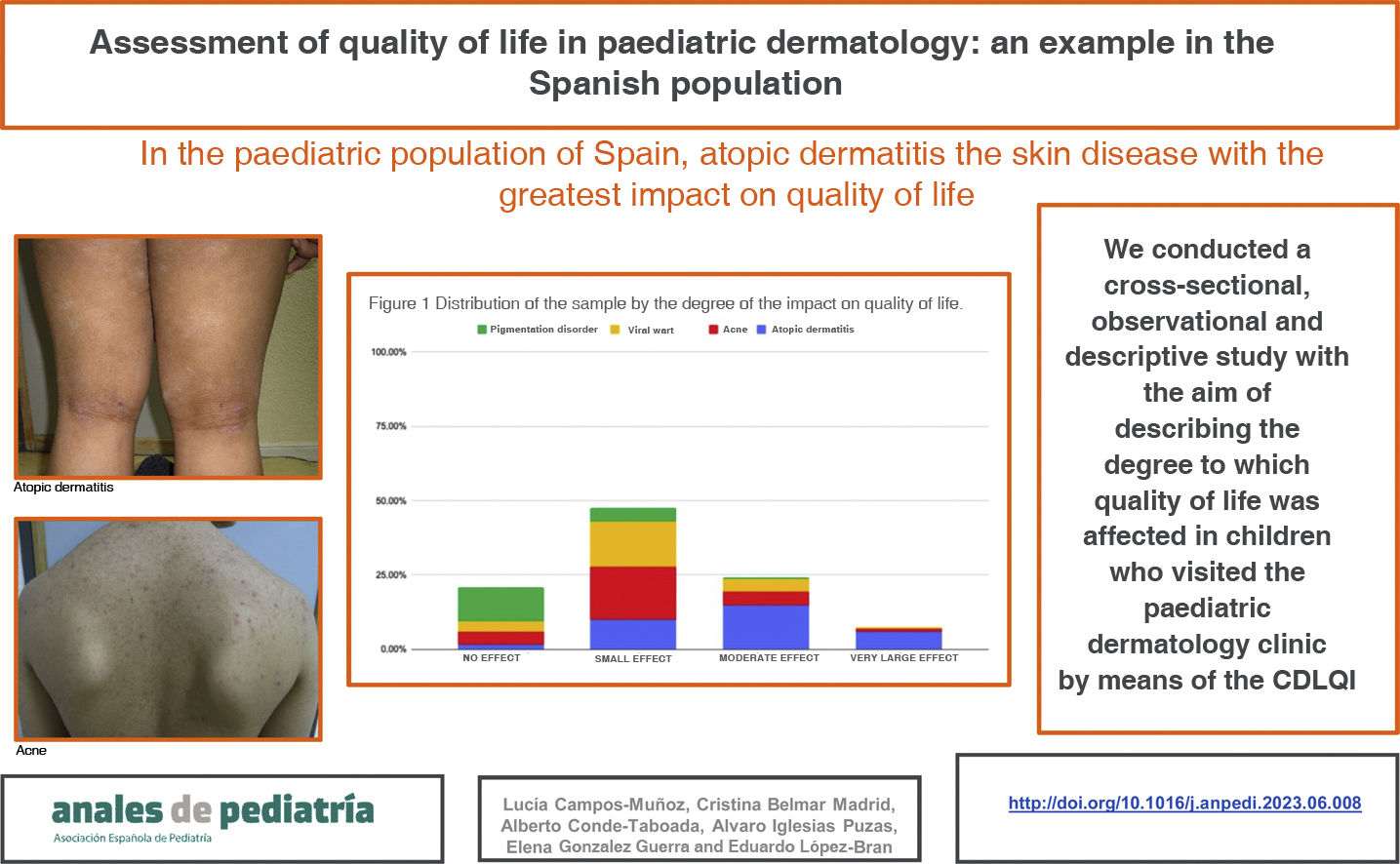

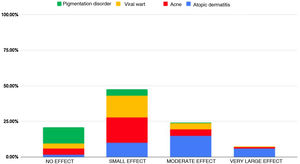

ResultsWe obtained a sample of 191 patients, 45.2% female and 54.8% male. The most frequent diagnosis was AD (31.9%), followed by acne (27.7%), VW/MC (23.5%) and skin pigmentation disorders (16.7%). The effect on quality of life was small in 47.64% of the sample, moderate in 24.08%, negligible in 20.94% and very large in 7.32%. None of the patients had scores reflecting an extremely large effect on quality of life. Fig. 1 presents the distribution of the sample by degree of impairment of quality of life and the proportion per category corresponding to each diagnostic group.

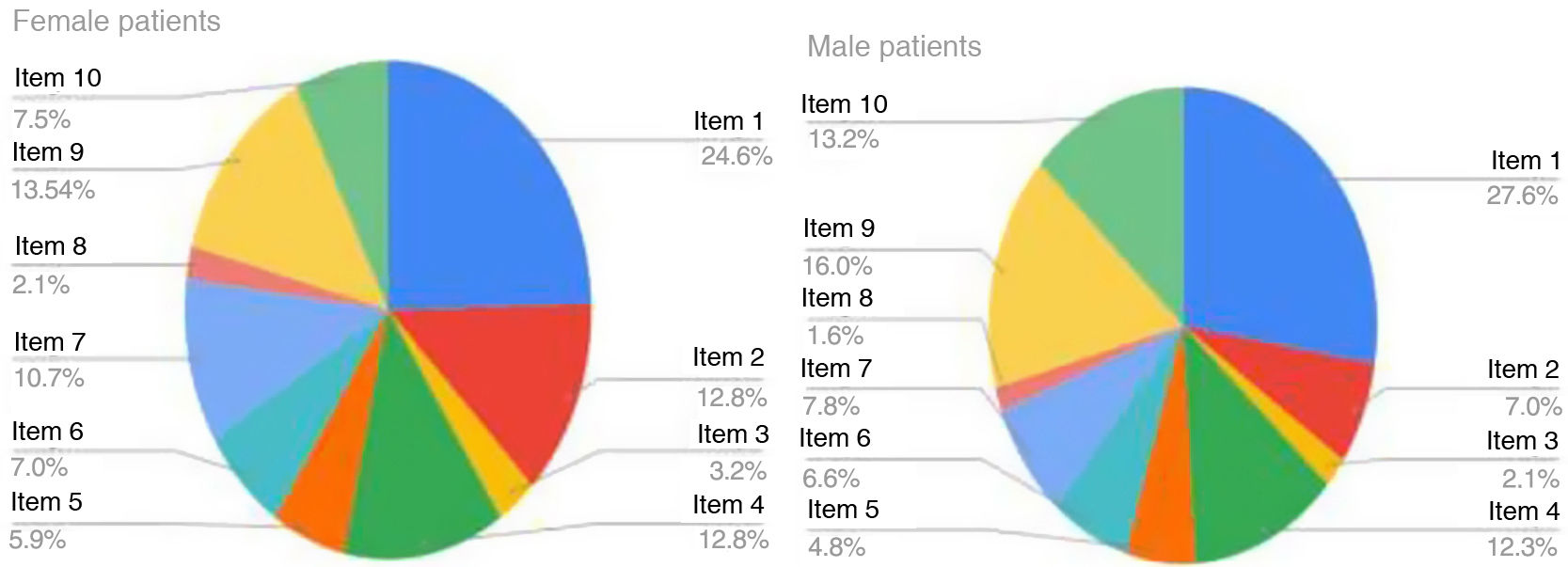

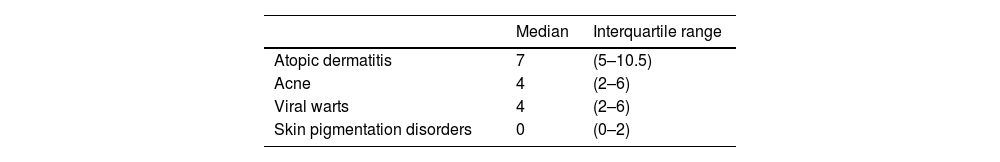

Analysing each diagnostic group separately, we obtained the following results (Table 2): the median score of patients with AD was 7 points, which corresponds to a moderate effect. The maximum score in the study occurred in this group (17 points, very large effect). The item with the highest score was item 1 (over the last week, how itchy, scratchy, sore or painful has your skin been?), with 78.5% of children with AD reporting that the symptoms affected them quite a lot or very much. Sixty-five percent of children with AD reported difficulty sleeping, although the effect was small in half of them. Fig. 2 shows the relative weight of each item in the total score in the AD group, that is, the impact of each item on the quality of life in these patients.

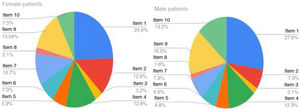

In patients with acne, the median score was of 4 points, corresponding to a small effect on quality of life. The item with the highest score was the one concerning feelings (item 2: over the last week, how embarrassed or self-conscious, upset or sad have you been because of your skin?), with 45.3% of children answering “quite a lot” (2 points) or “very much” (3 points) (Fig. 3).

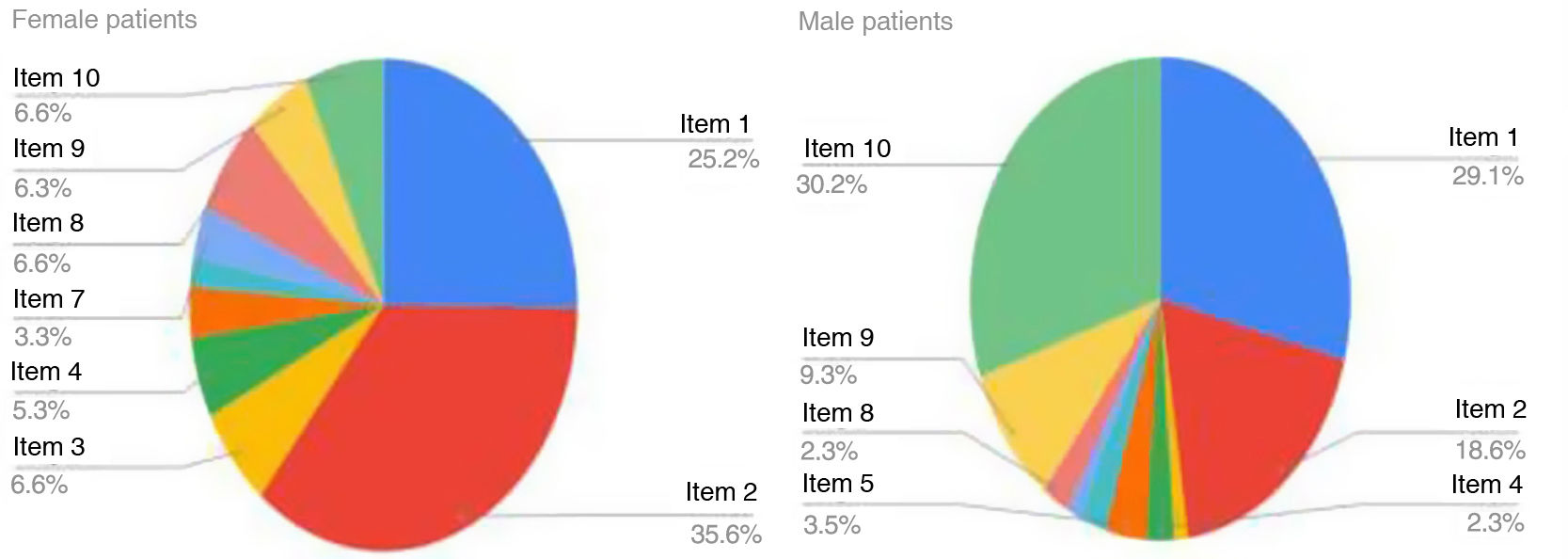

Patients with VW/MC had a median score of 4 points, corresponding to small effect on quality of life. The highest item score was for item 10 (how much of a problem has the treatment for your skin been?). In this group, 88.9% of children considered that their treatment caused them discomfort, with 31.1% choosing the “very much answer”, which is the highest possible score.

Thirty-two patients in the sample had skin pigmentation disorders: 27 had melanocytic nevi and 5 had café au lait spots. The median score in the questionnaire was 0, indicating no effect on quality of life in the group overall. This group had the lowest scores in every item. While 34.4% reported that their feelings were affected by their skin condition, 65.6% of these patients scored 0 points in this item.

We found statistically significant differences in comparing the diagnostic groups two by two: patients with AD had a poorer quality of life compared to each of the three other diagnostic groups (acne, VW/MC and skin pigmentation disorders). Patients with skin pigmentation disorders had a better quality of life compared to all other diagnostic groups (AD, acne and VW/MC).

DiscussionTo our knowledge, no other study to date has assessed the impact of different skin diseases on the quality of life of paediatric patients in Spain.

It is fair to say that although the quality of life of most patients managed in paediatric dermatology clinics is good, there are certain diagnoses, like AD, associated with greater impairment of quality of life (chiefly due to itching and insomnia), and therefore require more intensive treatment and a greater involvement on our part, as health care professionals, in pursuit of their wellbeing.7–9 Our findings warrant considering the need to increase the duration of visits sufficiently to offer adequate care for children with AD and their familias,10 in order to provide specific information on the factors that can worsen the disease.11,12 At the same time, they justify the considerable expenditure that may be required to provide novel treatments for AD (biologic agents, JAK inhibitors),13 as this is one of the skin diseases associated with severe impairment of quality of life in the paediatric age group.14,15 This finding was consistent with previous evidence from studies conducted in different countries: a study in the United Kingdom that assessed the impact on quality of life of different skin diseases in paediatric patients found greater impairment in association with AD, followed by psoriasis and urticaria2; and another study only found greater impairment in patients with scabies or psoriasis compared to AD.16 A meta-analysis published in 2016 also found greater impairment in patients with AD, followed by patients with acne, alopecia and molluscum contagiosum.17

In our study, patients with acne were the group with the greatest impairment of quality of life following the AD group, chiefly on account of the impact on feelings, and with a greater effect on female versus male patients. Multiple studies have confirmed the psychological impact of acne18–20 and supported a causal relationship between acne and the emotional state of the patient, with the presence of acne associated with a greater incidence of depression and anxiety.21,22 This is an aspect that families and other health care professionals are not always aware of and it justifies the treatment of acne in every case, even in patients with mild lesions, as the psychological impact can be significant nonetheless, and it is not always apparent during visits.

It is worth noting that in patients with MC/VW, the dimension with the highest scores in the questionnaire was the impact on quality of life caused by the treatment. Since many of these patients received cryotherapy, we may need to consider a change in the approach to their management, using less painful options, such as keratolytic therapy.23

Lastly, we may conclude that melanocytic nevi and café au lait spots do not tend to cause significant impairment of quality of life, although up to one third of patients may experience emotional problems secondary to these conditions. Since surgical removal of nevi is generally a simple procedure, it may be beneficial to ask patients whether the nevus they are seeking care for causes them sadness, embarrassment, etc, to identify potential candidates for surgery.24

One of the limitations of our study is the exclusion of skin diseases that are less prevalent in the Spanish paediatric population, like psoriasis, urticaria or alopecia. The study may also be affected by selection bias, as the patients in the sample required specialised care, and the observed impact on quality of life may have resulted from more severe forms of disease.25 Furthermore, the analysis was not stratified by diagnostic group.

In conclusion, AD was, among the common skin diseases, the one with the greatest impact on the quality of life in our ca sample of Spanish children, although other diseases can also have a considerable impact on quality of life.

FundingThis research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.