The temporal evolution of the prevalence of asthma described in the ISAAC (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood) in 2002 is unknown, or if the geographical or age differences are maintained in Spain.

ObjectiveTo describe the prevalence of asthma symptoms in different Spanish geographic areas and compare it with that of those centers that participated in the ISAAC.

MethodsCross-sectional study of asthma prevalence, carried out in 2016–2019 with 19,943 adolescents aged 13−14 years and 17,215 schoolchildren aged 6−7 years from 6 Spanish geographical areas (Cartagena, Bilbao, Cantabria, La Coruña, Pamplona and Salamanca). Asthma symptoms were collected using a written questionnaire and video questionnaire according to the Global Asthma Network (GAN) protocol.

ResultsThe prevalence of recent wheezing (last 12 months) was 15.3% at 13−14 years and 10.4% at 6−7 years, with variations in adolescents, from 19% in Bilbao to 10.2% in Cartagena; and in schoolchildren, from 11.7% in Cartagena to 7% in Pamplona. These prevalences were higher than those of the ISAAC (10.6% in adolescents and 9.9% in schoolchildren). 21.3% of adolescents and 12.4% of schoolchildren reported asthma at some time.

ConclusionsThere is a high prevalence of asthmatic symptoms with an increase in adolescents and a stabilization in Spanish schoolchildren with respect to the ISAAC. Geographic variations in asthma prevalence are not so clearly appreciated, but areas with high prevalences maintain high numbers.

Se desconoce la evolución temporal de la prevalencia de asma descrita en el ISAAC (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood) en 2002 o si las diferencias geográficas o por edades se mantienen en España.

ObjetivoDescribir la prevalencia de los síntomas de asma en distintas áreas geográficas españolas y compararla con la de aquellos centros que participaron en el ISAAC.

MétodosEstudio transversal de prevalencia de asma, realizado en 2016–2019 a 19,943 adolescentes de 13−14 años y 17,215 escolares de 6−7 años de 6 áreas geográficas españolas (Cartagena, Bilbao, Cantabria, La Coruña, Pamplona y Salamanca). Los síntomas de asma se recogieron mediante un cuestionario escrito y videocuestionario según el protocolo Global Asthma Network (GAN).

ResultadosLa prevalencia de sibilancias recientes (últimos 12 meses) fue del 15,3% a los 13−14 años y del 10,4% a los 6−7 años, con variaciones en los adolescentes, desde un 19% en Bilbao hasta un 10,2% en Cartagena; y en los escolares, desde un 11,7% en Cartagena hasta un 7% en Pamplona. Estas prevalencias fueron superiores a las del ISAAC (10,6% en adolescentes y 9,9% en los escolares). Un 21,3% de adolescentes y un 12,4% de los escolares refirieron asma alguna vez.

ConclusionesExiste una alta prevalencia de síntomas asmáticos con un incremento en los adolescentes y una estabilización en los escolares españoles con respecto al ISAAC. No se aprecian tan claramente variaciones geográficas en la prevalencia de asma, pero las áreas que tenían prevalencias elevadas mantienen cifras altas.

Asthma is a common chronic disease in childhood and adolescence, with a prevalence that varies between geographical regions and age groups.1,2 According to the Global Burden of Disease study, asthma is the leading cause of disability, measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), in children aged 5–14 years in developed countries.3

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC, 1992–2012) has contributed a vast collection of global epidemiological data on aspects such as prevalence, risk factors and protective factors (http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/), as well as the identification of candidate genes for wheezing and allergy4 and different asthma phenotypes.5 The first data on the prevalence of asthma in Spain collected in multiple centres with a shared, standardised and validated methodology became available in 1998. The data showed a prevalence of asthma in the past year of 9.3% in children aged 13–14 years and of 6.2% in children aged 6–7 years.1

The data obtained in phase III of the ISAAC study (ISAAC-III, 2002–2003) in Spain suggested that the Mediterranean diet may be protective against asthma in school-age children and adolescents,6–8 in addition to highlighting the relevance of obesity in this disease.9 This phase also established 2 thresholds for the prevalence of asthma, confirming an increase to up to 9.9% in children aged 6–7 years and stabilization at 10.6% in adolescents, with identification of a high-prevalence geographical area corresponding to Green Spain (the “cornisa cantábrica”) with a prevalence in adolescents of 12.8% in Bilbao, 15.2% in A Coruña, 15.3% in Asturias and 16.7% in Cantabria.10–12 Other relevant findings included variations associated with climate13,14 and the considerable impact of vaccination with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)15 or urban environmental pollution16 in the prevalence of asthma in Spain.

At present, we do not know if the observed temporal trends in the prevalence of asthma, with a plateau in adolescents and an increase in younger children, or the geographical differences described in the ISAAC-III have been sustained. Furthermore, while the prevalence of asthma and the associated risk or protective factors are well defined in some instances, these factors may behave differently in different locations and at different times.

In this context, and applying the ISAAC methodology, the Global Asthma Network (GAN) study (www.globalasthmanetwork.org) was launched with the aim of not only updating the information on the prevalence of asthma and the associated factors globally, but also to assess the associated costs and the approaches to its management. At present, the GAN network comprises 55 centres in 20 countries, including 6 in Spain (Murcia, Bilbao, Cantabria, La Coruña, Pamplona and Salamanca).17,18

The objective of our study was to describe the current prevalence of asthma symptoms in GAN centres in Spain and compare it with the prevalence found in the centres that participated in the ISAAC-III.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study applying the methodology described in the Global Asthma Network Manual for Global Surveillance (http://globalasthmanetwork.org/surveillance/manual/manual.php). It was based on data collected through standardised and previously validated questionnaires (http://globalasthmanetwork.org/surveillance/manual/validation.php) in a general sample, with an estimated sample size of 3000 participants per age group (13/14 years and 6/7 years) required to allow detection of differences in asthma prevalence of 3% or greater with a power of 90% and a level of confidence of 99%.17,18

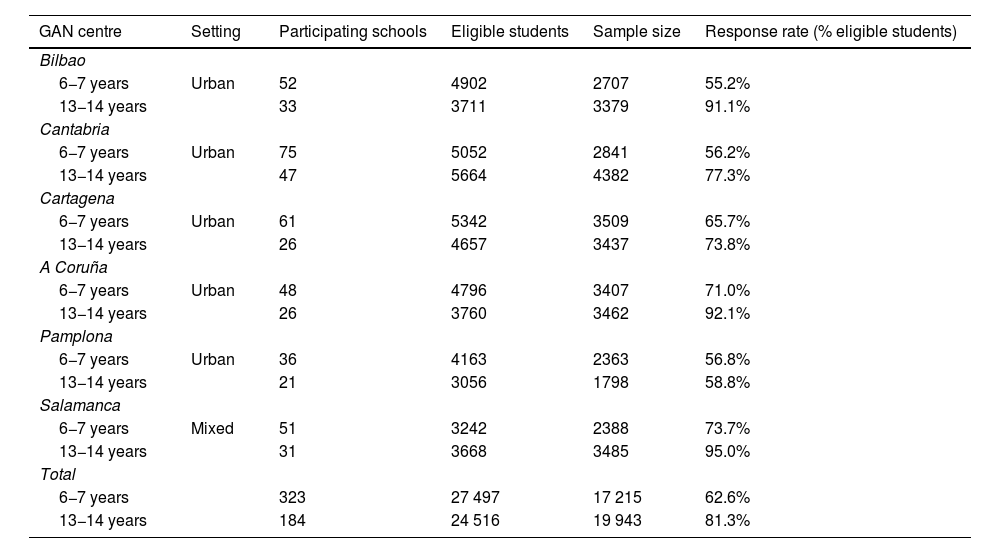

The field work took place during the school year at different points in the 2016–2019 period, depending on the centre (Table 1). The principal investigator of each participating centre contacted the corresponding Department of Education to obtain authorization to carry out the study in the selected primary and secondary schools, and subsequently communicated with the school principals, teachers and parents to inform them of the nature of the study. The sample included students enrolled in years 2 and 3 of compulsory secondary education (educación secundaria obligatoria, ESO) (aged 13/14 years) or years 1 and 2 of primary education (aged 6/7 years) in public or private schools. A schedule of visits to participating schools was established to guide the distribution and submission of self-administered paper- and video-based questionnaires completed by adolescents and the paper-based questionnaires for children aged 6/7 years completed by parents, and to oversee the entire process.

Characteristics of participating GAN centres.

| GAN centre | Setting | Participating schools | Eligible students | Sample size | Response rate (% eligible students) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilbao | |||||

| 6−7 years | Urban | 52 | 4902 | 2707 | 55.2% |

| 13−14 years | 33 | 3711 | 3379 | 91.1% | |

| Cantabria | |||||

| 6−7 years | Urban | 75 | 5052 | 2841 | 56.2% |

| 13−14 years | 47 | 5664 | 4382 | 77.3% | |

| Cartagena | |||||

| 6−7 years | Urban | 61 | 5342 | 3509 | 65.7% |

| 13−14 years | 26 | 4657 | 3437 | 73.8% | |

| A Coruña | |||||

| 6−7 years | Urban | 48 | 4796 | 3407 | 71.0% |

| 13−14 years | 26 | 3760 | 3462 | 92.1% | |

| Pamplona | |||||

| 6−7 years | Urban | 36 | 4163 | 2363 | 56.8% |

| 13−14 years | 21 | 3056 | 1798 | 58.8% | |

| Salamanca | |||||

| 6−7 years | Mixed | 51 | 3242 | 2388 | 73.7% |

| 13−14 years | 31 | 3668 | 3485 | 95.0% | |

| Total | |||||

| 6−7 years | 323 | 27 497 | 17 215 | 62.6% | |

| 13−14 years | 184 | 24 516 | 19 943 | 81.3% | |

The main instrument in data collection was the validated questionnaire, which includes sections on the symptoms of asthma and other allergic diseases, their severity, use of resources, risk and/or protective factors and medication. The question was translated from English to Spanish and back-translated to English applying the ISAAC methodology to ensure that the original meaning of the items was retained.19 Adolescents also completed a video questionnaire, translated to Spanish, that includes 5 scenarios in which individuals of different ages experience asthma exacerbations of varying severity and in different contexts. The Spanish version can be downloaded at http://pediatria.imib.es/portal/instituto/pediatria_gan.jsf, and the specific variables under study and their coding at http://globalasthmanetwork.org/surveillance/manual/coding.php. The primary variable was the presence of wheezing in the past year, defined as a “yes” answer to the item asking whether the child or adolescent had experienced wheezing or whistling in the chest in the past 12 months. Severe wheeze was defined as having experienced 4 or more wheezing attacks, or 1 or more awakenings at night due to wheezing per week, or experiencing wheezing severe enough to limit speech, all of it in reference to the past 12 months. A positive history of asthma was defined as a “yes” answer to “Have you/has this child ever had asthma?”.

The questionnaires were anonymised and scanned for reading in the coordinating centre in Cartagena (Murcia) with a Fujitsu fi-7700 scanner with optical mark recognition (OMR) software (Remark Office OMR version 10; Gravic Inc; Malvern, PA, USA). We performed a descriptive analysis of the variables followed by a comparative bivariate analysis using the chi square test to estimate possible differences based on sex in participating centres. Results were considered statistically significance if the P value was 0.05 or less. The statistical analysis was performed with the software STATA version 15 (College Station, TX, USA).

The GAN study was approved in the national coordinating centre by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca in Murcia, and subsequently validated and approved in each participating centre. In adolescents, we obtained informed consent from the parents.

ResultsThe GAN study in Spain involved the participation of 6 centres with a sample of 19 943 adolescents aged 13–14 years and 17 215 schoolchildren aged 6–7 years. The sample of adolescents was recruited from 184 schools and the sample of schoolchildren aged 6–7 years from 323 schools (Table 1). Participation was higher in the 13/14 years group (overall, 81.3%; range, 58.8%–95%) compared to the 6/7 years group (overall, 62.6%; range, 55.2%–73.7%).

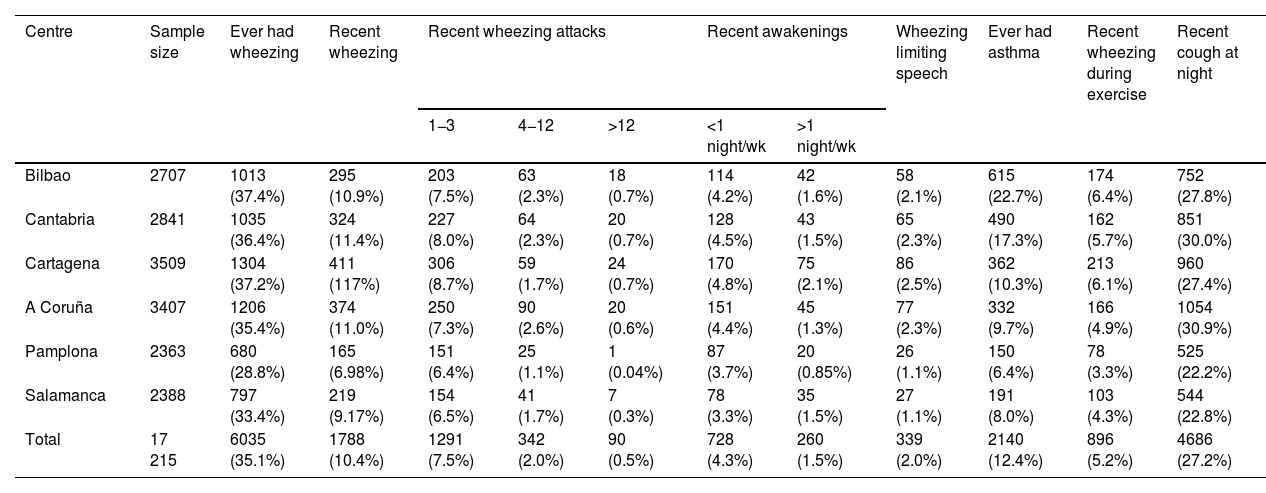

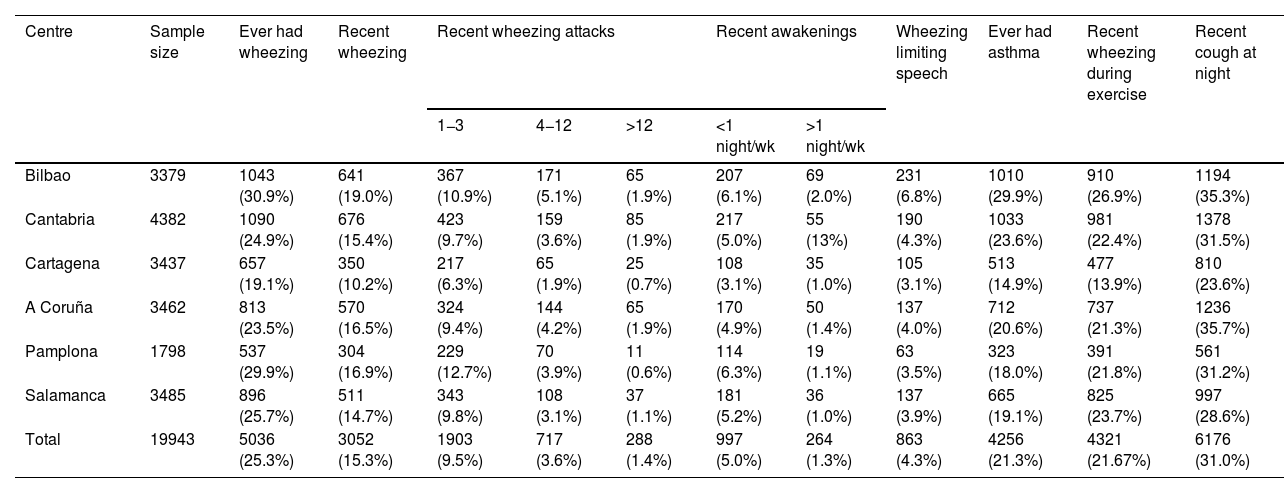

Tables 2 and 3 present the prevalence figures obtained through the paper-based questionnaire in each age group. The overall prevalence of recent wheezing for the total of participating GAN centres was 15.3% in adolescents and 10.4% in schoolchildren. As regards variation, the prevalence in adolescents ranged from 10.2% in Cartagena to 19% in Bilbao. There was less variation in schoolchildren, with a maximum of 11.7% in Cartagena and a minimum of 7% in Pamplona. In the group aged 6/7 years, only Salamanca and Pamplona had a prevalence under 10%. The prevalence of a positive history of asthma (ever had asthma) was also high: 21.3% in adolescents and 12.4% in schoolchildren.

Prevalence of asthma symptomsa. Paper-based GAN questionnaire in schoolchildren aged 6–7 years.

| Centre | Sample size | Ever had wheezing | Recent wheezing | Recent wheezing attacks | Recent awakenings | Wheezing limiting speech | Ever had asthma | Recent wheezing during exercise | Recent cough at night | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1−3 | 4−12 | >12 | <1 night/wk | >1 night/wk | ||||||||

| Bilbao | 2707 | 1013 (37.4%) | 295 (10.9%) | 203 (7.5%) | 63 (2.3%) | 18 (0.7%) | 114 (4.2%) | 42 (1.6%) | 58 (2.1%) | 615 (22.7%) | 174 (6.4%) | 752 (27.8%) |

| Cantabria | 2841 | 1035 (36.4%) | 324 (11.4%) | 227 (8.0%) | 64 (2.3%) | 20 (0.7%) | 128 (4.5%) | 43 (1.5%) | 65 (2.3%) | 490 (17.3%) | 162 (5.7%) | 851 (30.0%) |

| Cartagena | 3509 | 1304 (37.2%) | 411 (117%) | 306 (8.7%) | 59 (1.7%) | 24 (0.7%) | 170 (4.8%) | 75 (2.1%) | 86 (2.5%) | 362 (10.3%) | 213 (6.1%) | 960 (27.4%) |

| A Coruña | 3407 | 1206 (35.4%) | 374 (11.0%) | 250 (7.3%) | 90 (2.6%) | 20 (0.6%) | 151 (4.4%) | 45 (1.3%) | 77 (2.3%) | 332 (9.7%) | 166 (4.9%) | 1054 (30.9%) |

| Pamplona | 2363 | 680 (28.8%) | 165 (6.98%) | 151 (6.4%) | 25 (1.1%) | 1 (0.04%) | 87 (3.7%) | 20 (0.85%) | 26 (1.1%) | 150 (6.4%) | 78 (3.3%) | 525 (22.2%) |

| Salamanca | 2388 | 797 (33.4%) | 219 (9.17%) | 154 (6.5%) | 41 (1.7%) | 7 (0.3%) | 78 (3.3%) | 35 (1.5%) | 27 (1.1%) | 191 (8.0%) | 103 (4.3%) | 544 (22.8%) |

| Total | 17 215 | 6035 (35.1%) | 1788 (10.4%) | 1291 (7.5%) | 342 (2.0%) | 90 (0.5%) | 728 (4.3%) | 260 (1.5%) | 339 (2.0%) | 2140 (12.4%) | 896 (5.2%) | 4686 (27.2%) |

Prevalence of asthma symptomsa. Paper-based GAN questionnaire in adolescents aged 13–14 years.

| Centre | Sample size | Ever had wheezing | Recent wheezing | Recent wheezing attacks | Recent awakenings | Wheezing limiting speech | Ever had asthma | Recent wheezing during exercise | Recent cough at night | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1−3 | 4−12 | >12 | <1 night/wk | >1 night/wk | ||||||||

| Bilbao | 3379 | 1043 (30.9%) | 641 (19.0%) | 367 (10.9%) | 171 (5.1%) | 65 (1.9%) | 207 (6.1%) | 69 (2.0%) | 231 (6.8%) | 1010 (29.9%) | 910 (26.9%) | 1194 (35.3%) |

| Cantabria | 4382 | 1090 (24.9%) | 676 (15.4%) | 423 (9.7%) | 159 (3.6%) | 85 (1.9%) | 217 (5.0%) | 55 (13%) | 190 (4.3%) | 1033 (23.6%) | 981 (22.4%) | 1378 (31.5%) |

| Cartagena | 3437 | 657 (19.1%) | 350 (10.2%) | 217 (6.3%) | 65 (1.9%) | 25 (0.7%) | 108 (3.1%) | 35 (1.0%) | 105 (3.1%) | 513 (14.9%) | 477 (13.9%) | 810 (23.6%) |

| A Coruña | 3462 | 813 (23.5%) | 570 (16.5%) | 324 (9.4%) | 144 (4.2%) | 65 (1.9%) | 170 (4.9%) | 50 (1.4%) | 137 (4.0%) | 712 (20.6%) | 737 (21.3%) | 1236 (35.7%) |

| Pamplona | 1798 | 537 (29.9%) | 304 (16.9%) | 229 (12.7%) | 70 (3.9%) | 11 (0.6%) | 114 (6.3%) | 19 (1.1%) | 63 (3.5%) | 323 (18.0%) | 391 (21.8%) | 561 (31.2%) |

| Salamanca | 3485 | 896 (25.7%) | 511 (14.7%) | 343 (9.8%) | 108 (3.1%) | 37 (1.1%) | 181 (5.2%) | 36 (1.0%) | 137 (3.9%) | 665 (19.1%) | 825 (23.7%) | 997 (28.6%) |

| Total | 19943 | 5036 (25.3%) | 3052 (15.3%) | 1903 (9.5%) | 717 (3.6%) | 288 (1.4%) | 997 (5.0%) | 264 (1.3%) | 863 (4.3%) | 4256 (21.3%) | 4321 (21.67%) | 6176 (31.0%) |

As regards variables associated with asthma severity, we found a prevalence of wheezing impeding speech of 4.3% in adolescents and 2% in schoolchildren. The proportions of patients that reported 4–12 and more than 12 wheezing attacks in the past year were 3.6% and 1.4%, respectively, in adolescents, and 2% and 0.5%, respectively, in schoolchildren. The prevalence of sleep disturbances (awakening due to wheezing 1 or more nights per week in the recent past) was 1.3% in adolescents and 1.5% in schoolchildren.

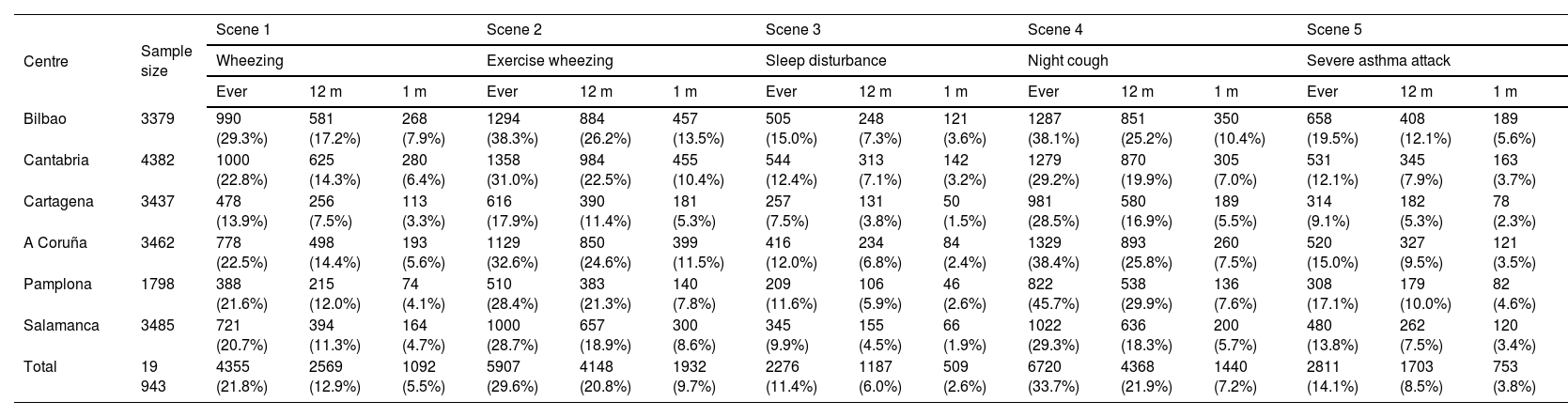

The analysis of asthma symptoms assessed through the video questionnaire in adolescents (Table 4) yielded a lower prevalence of recent wheezing compared to the paper-based questionnaire in every centre, with an overall prevalence of 12.9%, and differences between the 2 questionnaires ranging from a minimum of 7.5% in Cartagena to a maximum of 17.2% in Bilbao. This was not the case when we compared the prevalence of severe asthma exacerbations obtained with the 2 instruments, as the pattern went in the other direction, with a lower prevalence obtained with the video questionnaire compared to the paper-based one (8.5% vs 4.3%). When it came to the sleep disturbances caused by wheezing in the past 12 months, there was no overall difference in prevalence between the 2 instruments (video questionnaire, 6% vs paper questionnaire, 6.3%). The prevalence of cough at night was substantially lower in the video questionnaire compared to the paper-based one (21.9% vs 31%), while there was vary any difference in prevalence of recent wheezing associated with exercise (20.8% in the video questionnaire vs 21.7% in the paper questionnaire).

Prevalence of asthma symptomsa. Video GAN questionnaire in adolescents aged 13–14 years.

| Centre | Sample size | Scene 1 | Scene 2 | Scene 3 | Scene 4 | Scene 5 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheezing | Exercise wheezing | Sleep disturbance | Night cough | Severe asthma attack | ||||||||||||

| Ever | 12 m | 1 m | Ever | 12 m | 1 m | Ever | 12 m | 1 m | Ever | 12 m | 1 m | Ever | 12 m | 1 m | ||

| Bilbao | 3379 | 990 (29.3%) | 581 (17.2%) | 268 (7.9%) | 1294 (38.3%) | 884 (26.2%) | 457 (13.5%) | 505 (15.0%) | 248 (7.3%) | 121 (3.6%) | 1287 (38.1%) | 851 (25.2%) | 350 (10.4%) | 658 (19.5%) | 408 (12.1%) | 189 (5.6%) |

| Cantabria | 4382 | 1000 (22.8%) | 625 (14.3%) | 280 (6.4%) | 1358 (31.0%) | 984 (22.5%) | 455 (10.4%) | 544 (12.4%) | 313 (7.1%) | 142 (3.2%) | 1279 (29.2%) | 870 (19.9%) | 305 (7.0%) | 531 (12.1%) | 345 (7.9%) | 163 (3.7%) |

| Cartagena | 3437 | 478 (13.9%) | 256 (7.5%) | 113 (3.3%) | 616 (17.9%) | 390 (11.4%) | 181 (5.3%) | 257 (7.5%) | 131 (3.8%) | 50 (1.5%) | 981 (28.5%) | 580 (16.9%) | 189 (5.5%) | 314 (9.1%) | 182 (5.3%) | 78 (2.3%) |

| A Coruña | 3462 | 778 (22.5%) | 498 (14.4%) | 193 (5.6%) | 1129 (32.6%) | 850 (24.6%) | 399 (11.5%) | 416 (12.0%) | 234 (6.8%) | 84 (2.4%) | 1329 (38.4%) | 893 (25.8%) | 260 (7.5%) | 520 (15.0%) | 327 (9.5%) | 121 (3.5%) |

| Pamplona | 1798 | 388 (21.6%) | 215 (12.0%) | 74 (4.1%) | 510 (28.4%) | 383 (21.3%) | 140 (7.8%) | 209 (11.6%) | 106 (5.9%) | 46 (2.6%) | 822 (45.7%) | 538 (29.9%) | 136 (7.6%) | 308 (17.1%) | 179 (10.0%) | 82 (4.6%) |

| Salamanca | 3485 | 721 (20.7%) | 394 (11.3%) | 164 (4.7%) | 1000 (28.7%) | 657 (18.9%) | 300 (8.6%) | 345 (9.9%) | 155 (4.5%) | 66 (1.9%) | 1022 (29.3%) | 636 (18.3%) | 200 (5.7%) | 480 (13.8%) | 262 (7.5%) | 120 (3.4%) |

| Total | 19 943 | 4355 (21.8%) | 2569 (12.9%) | 1092 (5.5%) | 5907 (29.6%) | 4148 (20.8%) | 1932 (9.7%) | 2276 (11.4%) | 1187 (6.0%) | 509 (2.6%) | 6720 (33.7%) | 4368 (21.9%) | 1440 (7.2%) | 2811 (14.1%) | 1703 (8.5%) | 753 (3.8%) |

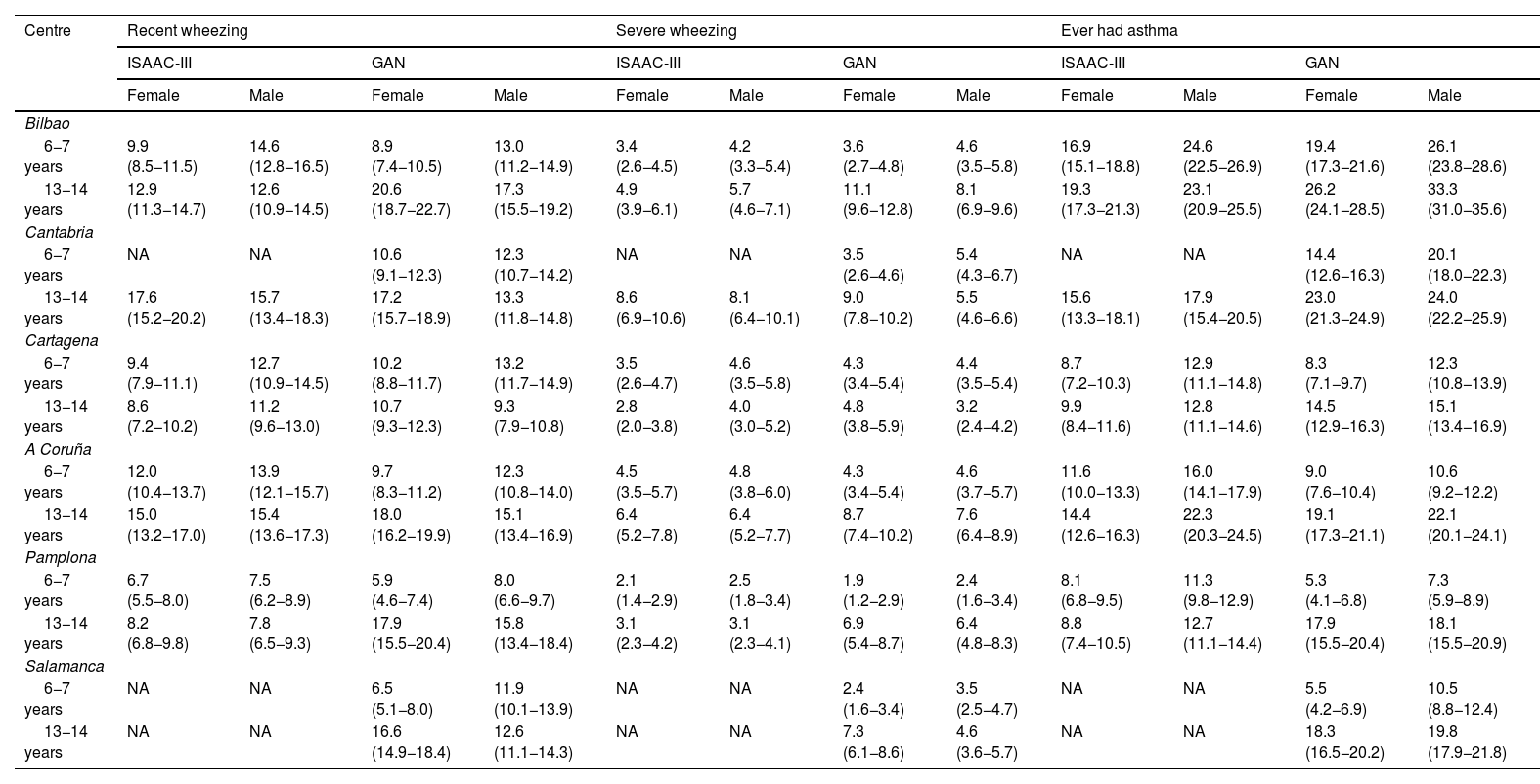

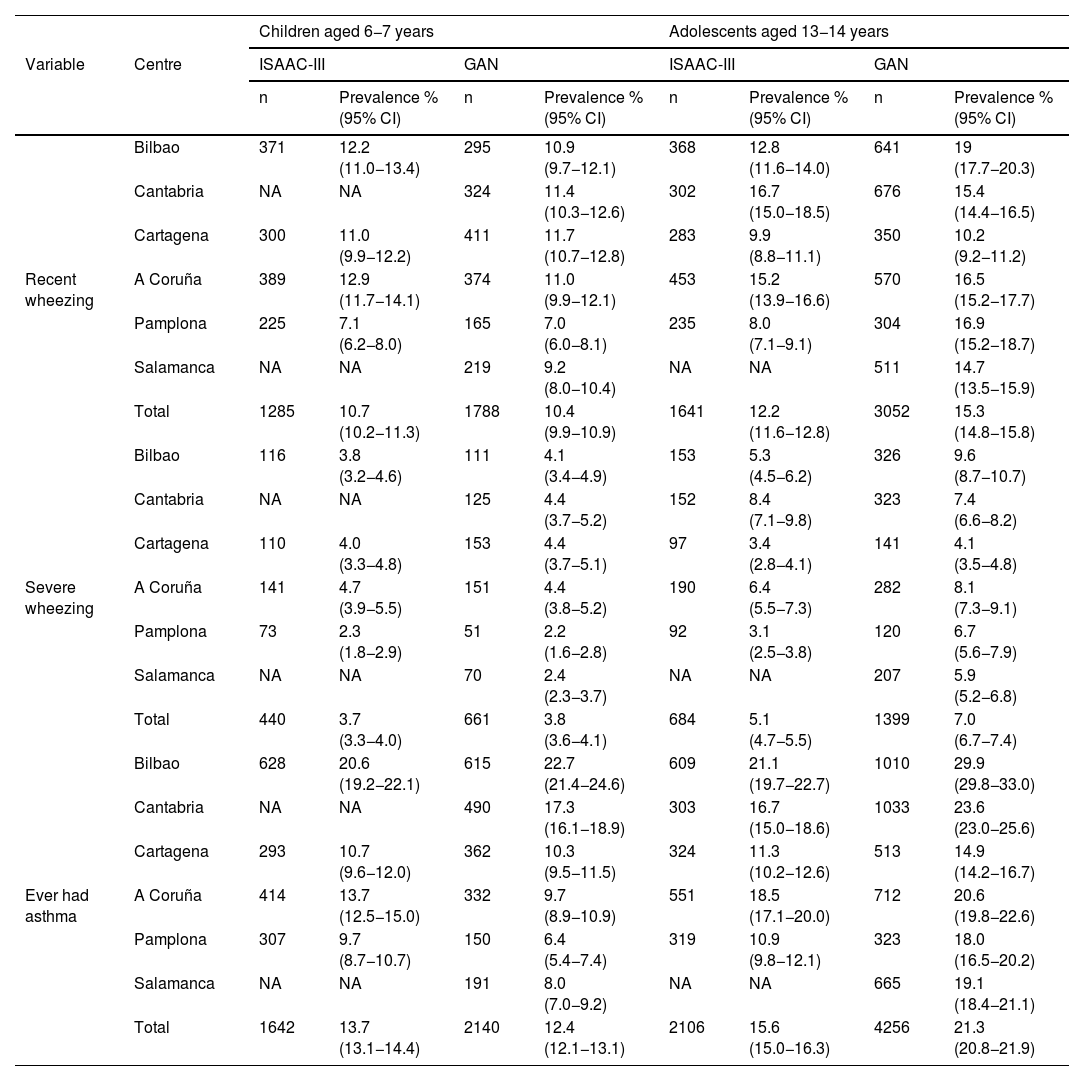

Tables 5 and 6 compare the prevalence of asthma symptoms in the past year obtained in the ISAAC-III (2002–2003) and the GAN study (2016–2019) in the 2 age groups. In adolescents, the prevalence of wheezing in the past year was higher in female adolescents in all GAN centres, with the opposite trend in schoolchildren, in which the prevalence was higher in boys. In some GAN centres, the observed difference based on sex was greater compared to the ISAAC-III. We also found a significant increase in the GAN study in the prevalence of wheezing in the past year in adolescents (15.3% vs 12.2%) and a stable prevalence in schoolchildren (10.4% vs 10.7%). When it came to severe wheezing, we found a significant increase in prevalence in adolescents (7% vs 5.1%) and no difference in schoolchildren (3.8% vs 3.7%).

Comparison of the prevalencea of asthma symptoms by sex in schoolchildren aged 6 to 7 years and adolescents aged 13 to 14 years in the ISAAC-III versus GAN study (written questionnaire).

| Centre | Recent wheezing | Severe wheezing | Ever had asthma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISAAC-III | GAN | ISAAC-III | GAN | ISAAC-III | GAN | |||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Bilbao | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | 9.9 (8.5−11.5) | 14.6 (12.8−16.5) | 8.9 (7.4−10.5) | 13.0 (11.2−14.9) | 3.4 (2.6−4.5) | 4.2 (3.3−5.4) | 3.6 (2.7−4.8) | 4.6 (3.5−5.8) | 16.9 (15.1−18.8) | 24.6 (22.5−26.9) | 19.4 (17.3−21.6) | 26.1 (23.8−28.6) |

| 13−14 years | 12.9 (11.3−14.7) | 12.6 (10.9−14.5) | 20.6 (18.7−22.7) | 17.3 (15.5−19.2) | 4.9 (3.9−6.1) | 5.7 (4.6−7.1) | 11.1 (9.6−12.8) | 8.1 (6.9−9.6) | 19.3 (17.3−21.3) | 23.1 (20.9−25.5) | 26.2 (24.1−28.5) | 33.3 (31.0−35.6) |

| Cantabria | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | NA | NA | 10.6 (9.1−12.3) | 12.3 (10.7−14.2) | NA | NA | 3.5 (2.6−4.6) | 5.4 (4.3−6.7) | NA | NA | 14.4 (12.6−16.3) | 20.1 (18.0−22.3) |

| 13−14 years | 17.6 (15.2−20.2) | 15.7 (13.4−18.3) | 17.2 (15.7−18.9) | 13.3 (11.8−14.8) | 8.6 (6.9−10.6) | 8.1 (6.4−10.1) | 9.0 (7.8−10.2) | 5.5 (4.6−6.6) | 15.6 (13.3−18.1) | 17.9 (15.4−20.5) | 23.0 (21.3−24.9) | 24.0 (22.2−25.9) |

| Cartagena | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | 9.4 (7.9−11.1) | 12.7 (10.9−14.5) | 10.2 (8.8−11.7) | 13.2 (11.7−14.9) | 3.5 (2.6−4.7) | 4.6 (3.5−5.8) | 4.3 (3.4−5.4) | 4.4 (3.5−5.4) | 8.7 (7.2−10.3) | 12.9 (11.1−14.8) | 8.3 (7.1−9.7) | 12.3 (10.8−13.9) |

| 13−14 years | 8.6 (7.2−10.2) | 11.2 (9.6−13.0) | 10.7 (9.3−12.3) | 9.3 (7.9−10.8) | 2.8 (2.0−3.8) | 4.0 (3.0−5.2) | 4.8 (3.8−5.9) | 3.2 (2.4−4.2) | 9.9 (8.4−11.6) | 12.8 (11.1−14.6) | 14.5 (12.9−16.3) | 15.1 (13.4−16.9) |

| A Coruña | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | 12.0 (10.4−13.7) | 13.9 (12.1−15.7) | 9.7 (8.3−11.2) | 12.3 (10.8−14.0) | 4.5 (3.5−5.7) | 4.8 (3.8−6.0) | 4.3 (3.4−5.4) | 4.6 (3.7−5.7) | 11.6 (10.0−13.3) | 16.0 (14.1−17.9) | 9.0 (7.6−10.4) | 10.6 (9.2−12.2) |

| 13−14 years | 15.0 (13.2−17.0) | 15.4 (13.6−17.3) | 18.0 (16.2−19.9) | 15.1 (13.4−16.9) | 6.4 (5.2−7.8) | 6.4 (5.2−7.7) | 8.7 (7.4−10.2) | 7.6 (6.4−8.9) | 14.4 (12.6−16.3) | 22.3 (20.3−24.5) | 19.1 (17.3−21.1) | 22.1 (20.1−24.1) |

| Pamplona | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | 6.7 (5.5−8.0) | 7.5 (6.2−8.9) | 5.9 (4.6−7.4) | 8.0 (6.6−9.7) | 2.1 (1.4−2.9) | 2.5 (1.8−3.4) | 1.9 (1.2−2.9) | 2.4 (1.6−3.4) | 8.1 (6.8−9.5) | 11.3 (9.8−12.9) | 5.3 (4.1−6.8) | 7.3 (5.9−8.9) |

| 13−14 years | 8.2 (6.8−9.8) | 7.8 (6.5−9.3) | 17.9 (15.5−20.4) | 15.8 (13.4−18.4) | 3.1 (2.3−4.2) | 3.1 (2.3−4.1) | 6.9 (5.4−8.7) | 6.4 (4.8−8.3) | 8.8 (7.4−10.5) | 12.7 (11.1−14.4) | 17.9 (15.5−20.4) | 18.1 (15.5−20.9) |

| Salamanca | ||||||||||||

| 6−7 years | NA | NA | 6.5 (5.1−8.0) | 11.9 (10.1−13.9) | NA | NA | 2.4 (1.6−3.4) | 3.5 (2.5−4.7) | NA | NA | 5.5 (4.2−6.9) | 10.5 (8.8−12.4) |

| 13−14 years | NA | NA | 16.6 (14.9−18.4) | 12.6 (11.1−14.3) | NA | NA | 7.3 (6.1−8.6) | 4.6 (3.6−5.7) | NA | NA | 18.3 (16.5−20.2) | 19.8 (17.9−21.8) |

NA, not available.

Comparison of the prevalencea of asthma symptoms in schoolchildren aged 6–7 years and adolescents aged 13–14 years in the ISAAC-III versus GAN study (written questionnaire).

| Children aged 6−7 years | Adolescents aged 13−14 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Centre | ISAAC-III | GAN | ISAAC-III | GAN | ||||

| n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Prevalence % (95% CI) | ||

| Recent wheezing | Bilbao | 371 | 12.2 (11.0−13.4) | 295 | 10.9 (9.7−12.1) | 368 | 12.8 (11.6−14.0) | 641 | 19 (17.7−20.3) |

| Cantabria | NA | NA | 324 | 11.4 (10.3−12.6) | 302 | 16.7 (15.0−18.5) | 676 | 15.4 (14.4−16.5) | |

| Cartagena | 300 | 11.0 (9.9−12.2) | 411 | 11.7 (10.7−12.8) | 283 | 9.9 (8.8−11.1) | 350 | 10.2 (9.2−11.2) | |

| A Coruña | 389 | 12.9 (11.7−14.1) | 374 | 11.0 (9.9−12.1) | 453 | 15.2 (13.9−16.6) | 570 | 16.5 (15.2−17.7) | |

| Pamplona | 225 | 7.1 (6.2−8.0) | 165 | 7.0 (6.0−8.1) | 235 | 8.0 (7.1−9.1) | 304 | 16.9 (15.2−18.7) | |

| Salamanca | NA | NA | 219 | 9.2 (8.0−10.4) | NA | NA | 511 | 14.7 (13.5−15.9) | |

| Total | 1285 | 10.7 (10.2−11.3) | 1788 | 10.4 (9.9−10.9) | 1641 | 12.2 (11.6−12.8) | 3052 | 15.3 (14.8−15.8) | |

| Severe wheezing | Bilbao | 116 | 3.8 (3.2−4.6) | 111 | 4.1 (3.4−4.9) | 153 | 5.3 (4.5−6.2) | 326 | 9.6 (8.7−10.7) |

| Cantabria | NA | NA | 125 | 4.4 (3.7−5.2) | 152 | 8.4 (7.1−9.8) | 323 | 7.4 (6.6−8.2) | |

| Cartagena | 110 | 4.0 (3.3−4.8) | 153 | 4.4 (3.7−5.1) | 97 | 3.4 (2.8−4.1) | 141 | 4.1 (3.5−4.8) | |

| A Coruña | 141 | 4.7 (3.9−5.5) | 151 | 4.4 (3.8−5.2) | 190 | 6.4 (5.5−7.3) | 282 | 8.1 (7.3−9.1) | |

| Pamplona | 73 | 2.3 (1.8−2.9) | 51 | 2.2 (1.6−2.8) | 92 | 3.1 (2.5−3.8) | 120 | 6.7 (5.6−7.9) | |

| Salamanca | NA | NA | 70 | 2.4 (2.3−3.7) | NA | NA | 207 | 5.9 (5.2−6.8) | |

| Total | 440 | 3.7 (3.3−4.0) | 661 | 3.8 (3.6−4.1) | 684 | 5.1 (4.7−5.5) | 1399 | 7.0 (6.7−7.4) | |

| Ever had asthma | Bilbao | 628 | 20.6 (19.2−22.1) | 615 | 22.7 (21.4−24.6) | 609 | 21.1 (19.7−22.7) | 1010 | 29.9 (29.8−33.0) |

| Cantabria | NA | NA | 490 | 17.3 (16.1−18.9) | 303 | 16.7 (15.0−18.6) | 1033 | 23.6 (23.0−25.6) | |

| Cartagena | 293 | 10.7 (9.6−12.0) | 362 | 10.3 (9.5−11.5) | 324 | 11.3 (10.2−12.6) | 513 | 14.9 (14.2−16.7) | |

| A Coruña | 414 | 13.7 (12.5−15.0) | 332 | 9.7 (8.9−10.9) | 551 | 18.5 (17.1−20.0) | 712 | 20.6 (19.8−22.6) | |

| Pamplona | 307 | 9.7 (8.7−10.7) | 150 | 6.4 (5.4−7.4) | 319 | 10.9 (9.8−12.1) | 323 | 18.0 (16.5−20.2) | |

| Salamanca | NA | NA | 191 | 8.0 (7.0−9.2) | NA | NA | 665 | 19.1 (18.4−21.1) | |

| Total | 1642 | 13.7 (13.1−14.4) | 2140 | 12.4 (12.1−13.1) | 2106 | 15.6 (15.0−16.3) | 4256 | 21.3 (20.8−21.9) | |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available.

The GAN study has contributed updated information in the prevalence of asthma symptoms in Spain, confirming that asthma continues to be a common affliction with a prevalence of wheezing in the recent past of 15.3% in adolescents and 10.4% in schoolchildren, reflecting an increase compared to the prevalence in 2002–2003 found in the ISAAC-III (10.6% and 9.9%, respectively).10,11 While the prevalence exhibited an increase in adolescents, it appeared to be plateauing in children. While the increase in adolescents may be partly explained by the smaller number of centres that participated in the GAN study and the absence of some of the centres included in the ISAAC-III (Castellon, Barcelona and Valladolid) where the prevalence of asthma had been low, it is likely that the observed increase was real, as the prevalence in the GAN centre in Pamplona, which also participated in the ISAAC-III, increased from 8% to 16.9%, and the GAN centre in Salamanca, which did not participate in the ISAAC-III, reported a current prevalence of 14.7%, much higher compared to the past prevalence in nearby centres, such as the one in Valladolid (prevalence of 8.2% in the ISAAC-III).

Our findings only partially confirmed the results of the ISAAC-III concerning geographical variations with a high-prevalence pattern in the Green Spain region. While the prevalence of asthma in adolescents continued to be high in the GAN centres located in this region, such as those in Bilbao, A Coruña and Cantabria (19%, 16.5% and 15.4% compared to 12.8%, 15.2% and 16.7% in the ISAAC-III), other centres, like those in Pamplona and Salamanca, also turned out to have a high prevalence (16.9% and 14.7%, respectively). Cartagena, the only centre in the Mediterranean region, reported a prevalence in adolescents similar to the past one (10.2% compared to 9.9% in the ISAAC-III), which could be indicative of a stabilization in this region in association with differences in climate and the hours of sun exposure.14

The geographical variation observed in asthma in the ISAAC-III in children aged 6–7 years could not be discerned as clearly in the GAN study. Thus, the prevalence observed in GAN centres located in Green Spain (of 10.9%, 11% and 11.4% in Bilbao, A Coruña and Cantabria, respectively) did not differ from the prevalence found in the only GAN centre in the Mediterranean region (Cartagena, with a prevalence that was only slightly greater at 11.7%). However, these four centres near the coast do differ from centres located inland and at higher altitudes, such as Pamplona and Salamanca, which reported lower figures of 7% and 9.1%, respectively. This coast-versus-inland pattern observed in in schoolchildren cannot be generalised to the entire country, nor the epidemiological factors at play in the difference identified, since the study did not include data for large regions, such as Andalusia, Catalonia, Madrid, the Balearic Islands or the Canary Islands. Other studies conducted in Spain, such as the International Study of Wheezing in Infants, have not found geographical differences in prevalence, with wheezing found in at least one third of infants under study independently of location,20,21 although it is well known that wheezing in infants differs from wheezing in school-age children and adolescents.

There is controversy regarding the global trend in asthma prevalence. In the ISAAC-III, some centres with a low asthma prevalence reported an increasing trend, while others with a high baseline prevalence reported decreases, especially in English-speaking countries and Western Europe.1 In the United States, the prevalence of asthma in the population aged less than 18 years increased from 8.7% to 9.4% in the 2001–2010 period, followed by a plateau until 2013 and a subsequent decrease to 7% by 2019.22–24 Data from the National Health Interview Survey of the United States also showed a prevalence peak of 10.9% at age 12–14 years. In Thailand, the data shows that the prevalence of asthma has stabilized in schoolchildren aged 6–7 years (14.6%), with a slight decrease in adolescents (12.5%).25 Other recent data show that the prevalence of asthma is currently stable in Finnish youth.26 The data from our study show that the prevalence of asthma is stabilizing in schoolchildren and increasing in adolescents, although the prevalence remains high in GAN centres that had previously reported a high prevalence in the ISAAC-III. There is likely a potential maximum prevalence in each population that could be reached in specific areas when all predisposed individuals exhibit symptoms, which could explain the asthma prevalence trends in different regions and countries.27

Exercise-induced asthma symptoms were frequent in adolescents, without differences in prevalence between the paper-based and video questionnaires (20.8% vs 21.6%). However, we ought to highlight the low prevalence in children aged 6–7 years based on parental reports (5.2% compared to 5.1% in the ISAAC-III), possibly due to a decreased frequency and intensity of physical activity and greater time spent playing at that age.10,11 We did not find a substantial difference in the prevalence of nocturnal dry cough in the past year obtained through the paper-based questionnaire (27.2% in schoolchildren versus 31% in adolescents), although it was greater compared to the ISAAC-III (18.9% and 23.1%, respectively).

On the other hand, a past history of asthma was reported in 21.3% of adolescents and 12.4% of schoolchildren, which, compared to the data of the ISAAC-III (14.3% and 11.8%, respectively) corroborates the significant increase in asthma in adolescents (with increases varying from 29.9% in Bilbao to 14.9% in Cartagena) and the stabilization of its prevalence in schoolchildren. The self-reporting of asthma indicates a medical diagnosis, which confirms the need of guaranteeing correct diagnosis and treatment of asthma, especially at a crucial stage like adolescence.

In our study, the comparison by sex revealed a greater prevalence in boys and female adolescents, with differences that were more frequently significant compared to the ISAAC-III. This finding was consistent with those of the GAN centres in Chile and Mexico, where female sex was found to be a significant risk factor for development of asthma in adolescence and female adolescents exhibited the highest prevalence of asthma, while the prevalence in the 6–7 years age group was greater in boys.28,29 The observed differences by sex are not clearly understood. Studies in animals show that oestrogens increase Th2-mediated airway inflammation and, on the other hand, in the early years of life, boys exhibit a greater disproportion than girls in the size and growth of the airways compared to the rest of the lung parenchyma.30

When we analysed severe wheezing, defined as the presence in the past year of 4 or more whistling attacks, 1 or more awakenings a week due to wheezing or any wheezing attack that impeded speech, we found a significant increase in prevalence in adolescents (7% in the GAN study vs 5.1% in the ISAAC-III).10,11 All of the above, in addition to 5% of adolescents reporting 4 or more asthma exacerbations in the past year, reflect poor asthma control which, combined with the poor adherence characteristic of adolescence, evinces a pressing need for asthma education programmes to achieve adequate self-management of the disease.

Although the obtained sample was large and representative enough to reduce selection bias, the fact that some of the centres that participated in the ISAAC did not participate in the GAN study could limit the generalization of the findings on the prevalence of asthma and its temporal trends in Spain. The study had other limitations characteristic of its cross-sectional design, like the inability to establish causal relationships or the use of questionnaires that may give rise to recall bias in parental responses, although limiting the questions to the past 12 months helped reduce this bias. As regards the diagnosis of asthma using data on symptoms obtained through questionnaires as opposed to a medical diagnosis, this is the best feasible approach to compare cities and countries in large-scale epidemiological studies.

In short, the GAN study in Spain, conducted in a large sample of adolescents aged 13–14 years and schoolchildren aged 6–7 years, found a high prevalence of asthma, with an increasing trend in adolescents and stabilization in schoolchildren. The geographical variations detected in 2002 were not as clearly discerned in this study, although it was confirmed that regions where the prevalence of asthma was high in the past continued to have a high prevalence. On the other hand, the observed increases in the prevalence of sleep disturbances, severe asthma and self-reported history of asthma reflect poor asthma control and suggest that asthma has been underdiagnosed and undertreated in recent years.

FundingThis study was funded by research grants from the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Valdecilla (IDIVAL) of Cantabria, PRIMVAL 17/01 and 18/01 (Centro Cantabria); the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III: Proyectos de Investigación en SaludPI17/00179 (Centro Cartagena), PI17/00756 (Centro Bilbao), PI17/00694 (Centro Pamplona); the Fundación María José Jove (Centro A Coruña); Gerencia Regional de Salud de la Junta de Castilla y León (GRS 1239/b/16) and the Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica, Alergología y Asma Pediátrica (Centro Salamanca).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the collaboration of the Departments of Education and Departments of Health of the autonomous communities where participating centres are located in Spain, and the cooperation of the teaching staff of primary and secondary schools and parents and students, without whose consent and altruistic help the study would not have been possible.

Cartagena GAN centre (national coordinating centre): L. García-Marcos, M. Sánchez-Solís, Paediatric Pulmonology and Allergy Unit, Hospital Infantil Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Universidad de Murcia. Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria IMIB, Murcia, Spain. A. Martínez-Torres, Paediatric Pulmonology and Allergy Unit and Nursing Research Group, Hospital Infantil Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria IMIB, Murcia, Spain. V. Pérez-Fernández, E. Morales Bartolomé, Universidad de Murcia. Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria IMIB, Murcia, Spain. J.J. Guillén-Pérez, J.F. Amoraga Bernal, J. Llamas Fernández and A. García Coy. Cartagena Public Health System. Department of Health of Murcia, Spain. Bilbao GAN centre: C. González Díaz, A. González Hermosa, J. Rementeria Radigales. Department of Paediatrics. Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao, Vizcaya, Spain. Cantabria GAN centre: A. Bercedo Sanz, L. Lastra Martínez, R. Pardo Crespo. S. Peñil Sánchez. Servicio Cántabro de Salud. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Valdecilla. IDIVAL. Cantabria, Spain. A Coruña GAN centre: A. López-Silvarrey Varela, Fundación María José Jove; Servicio Galego de Saúde (SERGAS), A Coruña, Spain. T.R. Pérez Castro, Cardiovascular Research Group (GRINCAR); Cardiovascular Epidemiology, Primary Care and Nursing (INIBIC); School of Nursing and Podiatry, Universidad de A Coruña, Spain. A. Otero Rodríguez, A. Garea Otero, A. Torrado Nogueira, J. Iglesias López, F.J. González Barcala. Servicio Galego de Saúde (SERGAS), A Coruña, Spain. R. Montero López, St. Josef Braunau Hospital, Braunau, Austria. Pamplona GAN centre: I. Aguinaga-Ontoso, F. Guillén-Grima, Department of Health Sciences, Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA), Pamplona, Navarra, Spain and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra (IdiSNA), Spain. E. Rayón-Valpuesta, J. Coque-Rubio, O. Alvarez-Flames, S. Sola-Cía, R. Saenz-Mendia, R. García-Orellan, X. Elizalde, Department of Health Sciences, Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA), Pamplona, Spain. IdiSNA, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra. S. Monje-Ortega, Hospital Santa Marina-Osakidetza, Bilbao, Vizcaya. Salamanca GAN centre: J. Pellegrini Belinchón, Centro de Salud Pizarrales, Salamanca, Spain. Department of Biomedical Sciences and Diagnosis, Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. S. Arriba-Méndez, Department of Paediatrics, Hospital Universitario Salamanca and Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Salamanca IBSAL, Spain. A. Marín-Cassinello, Department of Paediatric Pulmonology and Allergy, Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena, Murcia, Spain. M. Domínguez, Centro de Salud San Juan, Salamanca, Spain. MC. Sánchez–Jiménez, Centro de Salud Tejares, Salamanca and Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. M. M. López-González, Centro de Salud Pizarrales, Salamanca, Spain. M.C. Vega-Hernández, Department of Statistics, Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. M. Polo-De Dios. Centro de Salud Zamora Sur. Zamora, Spain.

Appendix A lists the members of the GAN Spain group.

Please cite this article as: Bercedo Sanz A, Martínez-Torres A, González Díaz C, López-Silvarrey Varela A, Pellegrini Belinchón FJ, Aguinaga-Ontoso I, et al. Prevalencia y evolución temporal de síntomas de asma en España. Estudio Global Asthma Network (GAN). An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;97:161–171.