In recent years, an abundance of information has spread in social media suggesting that infants should not be fed baby cereal (BC) products on account of their high free sugar content and their sweet taste.1 Proposed alternatives include corn starch, semolina, oatmeal or brown rice.

The advantages of introducing BC products in complementary feeding are their texture and the contribution of fibre, energy, iron and zinc, mainly. The disadvantages are the free sugar content and sweet taste of these products.2

The Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (Spanish Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, SEGHNP)3 recommends that the intake of free sugars until age 2 years amount to less than 5% of the total energy intake (TEI). Since consumption of fruit juice in the first year of life is currently discouraged, BC are the main source of free sugars in the infant’s diet.

In 2018, we reviewed the nutrient composition of 98 BC brands sold in Spain. Assuming a mean energy intake of 750 kcal/day in the second semester of life based on current recommendations, consumption of 25 g a day of BC would correspond to an intake of free sugars exceeding 5% of the TEI in 1 brand, or 5 brands in case of consumption of 30 g per day. The contribution of fibre of BC would amount to 1.2–1.5 g per day. In 2020, we reviewed 110 brands of BC and found an overall decrease in sugar content (the percentage of products with 5 or fewer grams of sugar per 100 g of product went from 18.3% to 30.9%) and an increase in the fibre content (45.4% compared to the previous 40.8%).4 At present, daily consumption of 25 or 30 g of BC of any commercial brand does not contribute more than 5% of the TEI in the form of free sugars.

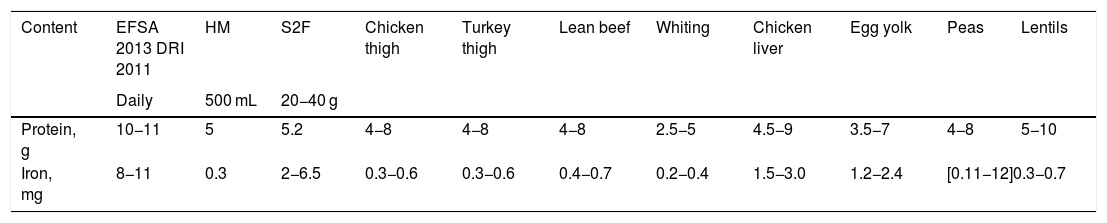

On the other hand, an excessive protein intake in the first months of life can predispose to future obesity. For this reason, several regional governments and paediatric societies in Spain, such as the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPap),5 recommend an intake of high biological value protein (HBVP) in complementary feeding of 20–40 g. Daily consumption of 500 mL of stage 2 formula and 20–40 g of meat or fish contribute 2.2–7.2 mg of iron (Table 1), based on data from the BEDCA Database on Food Nutrient Composition of Spain (https://bedca.net). Daily consumption of 500 mL of breastmilk contributes 0.5–1 mg of iron per day. Consumption of chicken liver or egg yolk can achieve iron intakes of 3.5 or 9.5 mg of iron a day in formula-fed infants or 1.5 or 2.7 mg a day in breastfed infants. Thus, daily consumption of 20–40 g of meat or fish in complementary feeding combined with 500 mL of stage 2 formula suffices to achieve the estimated required iron intake of 8–11 mg a day (11 mg according to the daily recommended intake of the Institute of Medicine [IOM-2011] and 8 mg according to the European Food Safety Authority [EFSA-2013]). The deficit is greater in breastfed infants.

Iron and protein contribution of 500 mL of stage 2 formula or human milk and 20–40 g of high-protein foods or legumes.

| Content | EFSA 2013 DRI 2011 | HM | S2F | Chicken thigh | Turkey thigh | Lean beef | Whiting | Chicken liver | Egg yolk | Peas | Lentils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 500 mL | 20−40 g | |||||||||

| Protein, g | 10−11 | 5 | 5.2 | 4−8 | 4−8 | 4−8 | 2.5−5 | 4.5−9 | 3.5−7 | 4−8 | 5−10 |

| Iron, mg | 8−11 | 0.3 | 2−6.5 | 0.3−0.6 | 0.3−0.6 | 0.4−0.7 | 0.2−0.4 | 1.5−3.0 | 1.2−2.4 | [0.11−12]0.3−0.7 | |

DRI, dietary reference intake; HM, human milk; S2F, stage 2 formula.

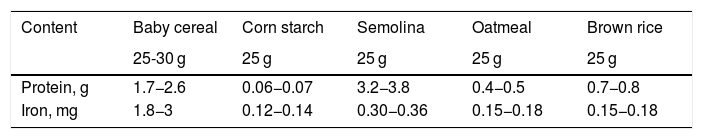

Consumption of BC may be necessary to achieve the recommended 8–11 mg of iron a day, as 25–30 g of BC contribute 1.8–3 mg of iron. In contrast, the alternatives to BC contribute 0.12–0.36 mg (Table 2). The consumption of legumes would not offer significant improvement (0.3−0.7 mg) (Table 1).

Iron and protein content of a 25- to 30-g portion of baby cereal, corn starch, semolina, oatmeal and brown rice.

| Content | Baby cereal | Corn starch | Semolina | Oatmeal | Brown rice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-30 g | 25 g | 25 g | 25 g | 25 g | |

| Protein, g | 1.7−2.6 | 0.06−0.07 | 3.2−3.8 | 0.4−0.5 | 0.7−0.8 |

| Iron, mg | 1.8−3 | 0.12−0.14 | 0.30−0.36 | 0.15−0.18 | 0.15−0.18 |

In conclusion, the recommendation of consuming lower amounts of HBVP in complementary feeding must be accompanied by the recommendation to consume foods rich in iron such as BC, as most alternatives do not contribute sufficient amounts of iron. Thus, BC should ideally be based on whole grains and not hydrolysed or hydrolysed to a lesser extent to reduce their free sugar content.6

Conflicts of interestThe author has received fees to give conferences from corporations that produce food products for infants and children, such as Abbott, Hero, Humana, Nestlé, Mead Johnson, Nutribén, Nutricia, Ordesa and Sanutri.

Please cite this article as: Vitoria Miñana I. Contenido actual de los cereales para lactantes y posibles alternativas: no todo vale en nutrición infantile. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;95:366–367.

Previous presentation: partial results of this study were presented at the XXVI Congress of the Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica, May 16–18, 2019, Santander, Spain.