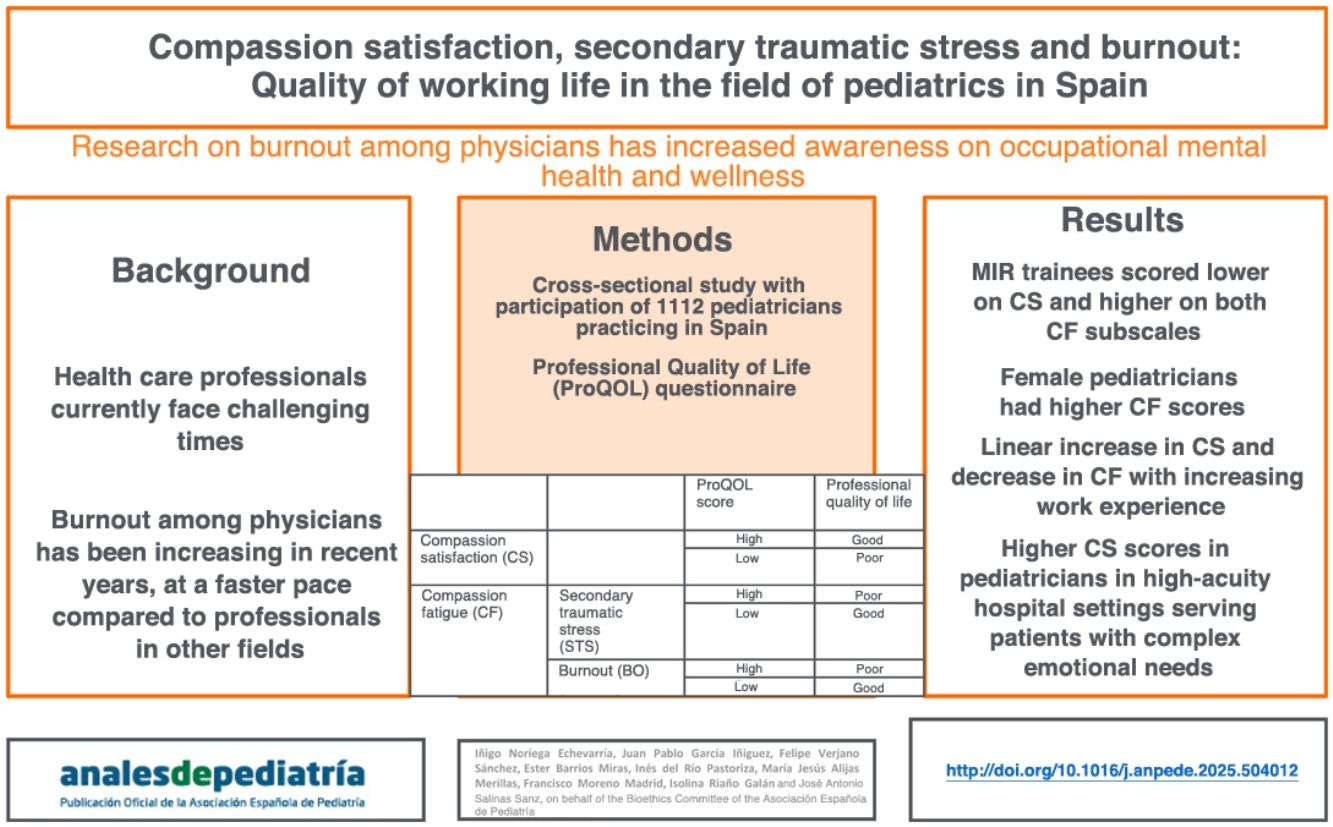

To determine the prevalence of compassion satisfaction (CS), secondary traumatic stress (STS) and job exhaustion or burnout (BO) in medical professionals specialized in pediatrics at the national level in Spain and determine which demographic and work-related factors affect their development.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study in pediatricians by means of questionnaires sent by the Spanish Association of Pediatrics (AEP) to its members, which were completed online and anonymously. We collected data on demographic variables, professional category (medical intern/resident [MIR] in pediatrics or pediatrician), main care setting and type of employment, specific field within pediatrics, main field of work, duration of work experience in general and time in current position. Care settings were further categorized into three groups: out-of-hospital, low-volume hospital and high-volume hospital (neonatology, intensive care, palliative care, oncology and emergency care). Participants completed the Spanish adaptation of the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) version 5 (Escala de Calidad de Vida Profesional) to assess three domains—CS, STS and BO—in relation to the past 30 days.

ResultsWe obtained a total of 1112 responses from pediatricians. Female respondents amounted to 78.9% of the sample. The distribution by care setting was 35.6% primary care, 34.9% low-volume hospital settings and 29.5% high-volume hospital settings. Most participants scored in the midrange of the three subscales of the ProQOL questionnaire: compassion satisfaction 60.7% (95% CI, 57.8−63.5), burnout 88.8% (95% CI, 86.8−90.5) and secondary traumatic stress 77.2% (95% CI, 74.7−79.6). Women scored significantly higher in the compassion fatigue subscales (BO and STS), while older age was associated with a linear increase in CS and an exponential decrease in STS. Permanent staff scored higher in CS and lower in BO and STS. We found a higher CS score in association with high-load hospital specialties and a higher BO score in association with low-load hospital specialties.

ConclusionsThe surveyed sample of Spanish pediatricians showed significant levels of compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress, with greater impact among younger and less experienced professionals, temporary workers and female doctors, highlighting the need for further study and targeted educational interventions.

Determinar la prevalencia de satisfacción por compasión (SC), estrés traumático secundario (SET) y burnout o agotamiento laboral (BO) en los profesionales médicos con especialidad de Pediatría a nivel nacional en España y determinar qué componentes demográficos y relacionados con el trabajo afectan a su desarrollo.

MétodoEstudio transversal entre pediatras mediante encuestas enviadas desde la Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP) a sus miembros, rellenadas virtualmente y en formato anónimo. Se recogieron variables demográficas, así como datos relativos a su situación profesional: pediatra en formación sanitaria especializada (MIR) o especialista en pediatría, ámbito principal de trabajo, tipo de relación laboral, área específica dentro de la pediatría, ámbito fundamental de trabajo, tiempo trabajado y tiempo en el puesto actual de trabajo. Las áreas específicas fueron categorizadas a su vez en tres grupos: extrahospitalarias, hospitalarias de baja carga y hospitalarias de alta carga (neonatología, cuidados intensivos, cuidados paliativos, oncología y urgencias). Los pediatras autocumplimentaron el cuestionario Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) en su versión 5 en castellano (Escala de Calidad de Vida Profesional) aplicado a los 30 días previos a su realización para evaluar al profesional en los tres dominios: SC, SET y BO.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 1112 respuestas de pediatras (el 78,9% mujeres). Por áreas específicas los participantes se distribuyeron en Atención primaria 35,6%, Hospitalaria de baja carga 34,9% y Hospitalaria de alta carga 29,5%. La mayoría de los participantes se situaron en el rango medio de las tres subescalas del cuestionario ProQOL: satisfacción por compasión (SC) 60,7% (IC95%: 57,8–63,5), burnout (BO) 88,8% (IC95%: 86,8–90,5) y estrés traumático secundario (SET) 77,2% (IC95%: 74,7–79,6). Se observó una puntuación significativamente mayor en las subescalas de FC (BO y SET) para mujeres, mientras que una mayor edad se relacionó con un aumento lineal de SC y un descenso exponencial de SET. El personal fijo presentó mayor puntuación en SC y menor en BO y SET. Se observó una mayor puntuación en SC para especialidades hospitalarias de alta carga y mayor puntuación de BO en las de baja carga.

ConclusionesLa población de pediatras españoles encuestados presentó niveles de afectación relevantes de FC y TS, más importantes en profesionales de menor edad, mujeres y en profesionales temporales, siendo necesario el estudio y abordaje formativo de estos aspectos en estos grupos en particular.

At present, health care professionals, especially doctors, are facing challenging times. Health care organizations demand that professionals be committed, quick, adaptable, resilient and engaged in improving the quality of institutions to develop more efficient care delivery models and increase productivity1: that they do more with less. In addition, the ongoing evaluation of patient satisfaction and assessment of health care quality with a greater focus on efficiency than on effectiveness can add to the pressure experienced by providers.

This ever-growing pressure has led many physicians to feel exhausted and unmotivated, weakening the bond between the medical profession and society. As a result, today we face a nationwide shortage of health care professionals, particularly in certain specialities.2–4 Multiple causes contribute to this phenomenon, involving various professional and social factors (social expectations, new models of care, progressive bureaucratization).5 Recent studies show that provider burnout has a negative impact on quality of care and patient safety and satisfaction.6,7 Furthermore, there is also evidence that this source of distress in physicians is associated with inadequate prescribing practices, ordering of unnecessary tests, an increased risk of malpractice lawsuits and lack of adherence of patients to the provider recommendations.7–11 A recent study estimated the prevalence of burnout in pediatricians at up to 36%, warranting a more in-depth study of this issue.5

In consequence, monitoring these issues and knowing the current situation has become an imperative.12 To this end, Stamm conceived of a scale to measure the perceived quality of one’s work, developing the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) tool. Its purpose is screening for issues in professional quality of life (pQoL), which has two key dimensions: compassion satisfaction (CS) and compassion fatigue (CF). In turn, compassion fatigue is composed of two aspects: secondary traumatic stress (STS) and burnout (BO).

The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of CS, STS and BO among physicians specialized in pediatrics in Spain and delve into the demographic and work-related factors associated with their development. The nature of the study was chiefly descriptive, through an exploratory analysis of the data, with no predefined working hypothesis, given the absence of previous similar studies in the field of pediatrics in Spain.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study by means of self-report questionnaires distributed through the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) to its members between February and March 2024, which were completed online on an anonymous basis. We collected data on demographic variables (sex/gender, age) and work-related variables, including whether the respondent was training as a medical resident/intern (MIR) in pediatrics or was an accredited pediatrician/pediatric specialist, the care setting and the type of institution (primary care center vs hospital) where the respondent worked most of the time, the type of employment contract (temporary/permanent), specific field within pediatrics, total years of experience and years worked in current position. Specific care settings were also categorized into three groups: out-of-hospital/primary care, low-acuity hospital-based care and high-acuity hospital-based care. The latter category included neonatal care, intensive care, palliative care, oncology and emergency care, based on the criteria of the researchers leading the project.

We also collected data corresponding to the Spanish adaptation of the ProQOL version 5, using the official manual to interpret the results, except in cases in which we opted to not standardize the results to facilitate their undertstanding.13 The scale comprises 30 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 [never] to 5 [very often]) that apply to the 30 days before completion to assess the following domains in the provider: CS, STS and BO. The compassion satisfaction subscale assesses the pleasure and satisfaction that providers derive from contributing to the wellbeing of patients and their families.14 On the other hand, the two subscales for compassion fatigue, STS and BO, differ both in nature and in their underlying causes. Secondary traumatic stress refers to the stress derived from the indirect exposure to the trauma experienced by others, usually through listening to the traumatic experiences reported by the patients, and therefore stems from an excess of empathy toward the traumatized patients,15,16 while BO is a state of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and low personal fulfilment due to chronic work-related stressors, such as excessive workloads, interpersonal conflict and the lack of resources or support in the workplace.17,18

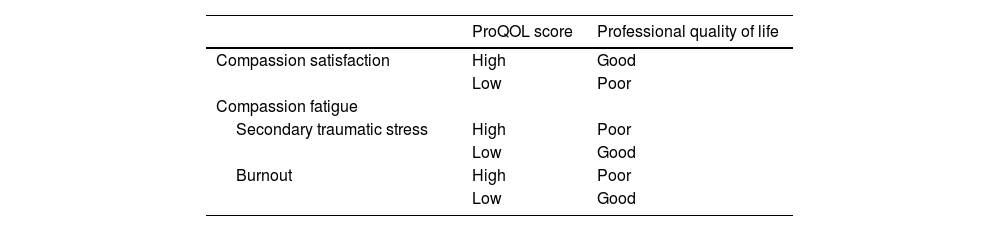

The instrument yields a score for each of these three subscales, which allow categorization of respondents into 3 groups: low, medium or high. The boundary between low/medium and medium/high scores correspond approximately to the 25th and 75th percentile in the population (23 and 43 points, respectively). While high scores in CS correspond to a higher pQoL, high scores in the BO and STS are indicative of a poorer pQoL. Different studies have found a good content and construct validity as well as adequate reliability for the ProQOL13,19 (Table 1).

We summarize quantitative data as mean and standard deviation and categorical data as percentages. We also conducted an exploratory analysis with bivariate tests based on the epidemiological variables of sex/gender and age, comparing MIR trainees versus the accredited pediatrician categories noted above, type of employment contract and years spent in the current position (excluding MIR trainees from the two latter variables). Comparisons were made with the Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) depending on the number of categories. In the case of ordinal categories, we also analyzed whether they followed a linear or exponential trend. In addition, we used backward stepwise logistic regression to analyze the association of each of the subscales with the study variables. The statistical analysis was performed with the Stata software, version 16.1.

Last of all, the study was exempt from explicit request of informed consent given that questionnaires were self-administered on a voluntary basis.

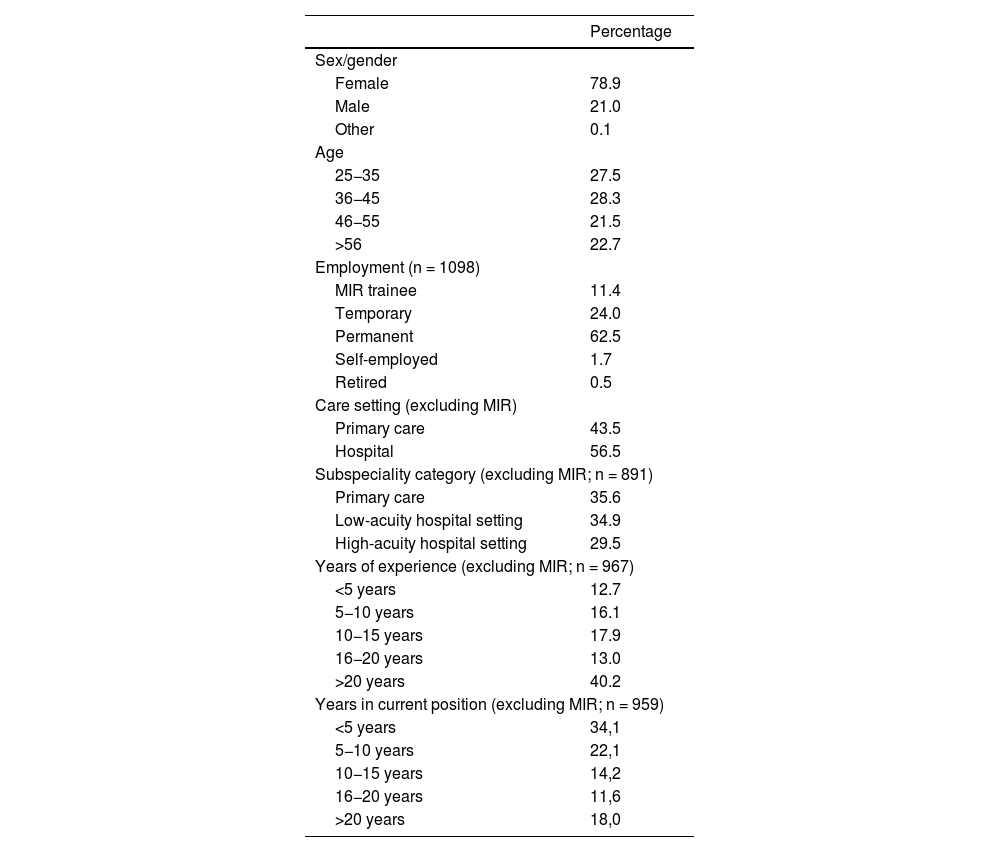

ResultsWe received a total of 1112 responses, with a response rate of 8.2%. Table 2 presents the main epidemiological results. There was a clear predominance of female respondents and a relatively uniform age distribution, and a majority of respondents held permanent positions (62.5%).

Demographic and work-related characteristics of the pediatricians who participated in the study.

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Sex/gender | |

| Female | 78.9 |

| Male | 21.0 |

| Other | 0.1 |

| Age | |

| 25−35 | 27.5 |

| 36−45 | 28.3 |

| 46−55 | 21.5 |

| >56 | 22.7 |

| Employment (n = 1098) | |

| MIR trainee | 11.4 |

| Temporary | 24.0 |

| Permanent | 62.5 |

| Self-employed | 1.7 |

| Retired | 0.5 |

| Care setting (excluding MIR) | |

| Primary care | 43.5 |

| Hospital | 56.5 |

| Subspeciality category (excluding MIR; n = 891) | |

| Primary care | 35.6 |

| Low-acuity hospital setting | 34.9 |

| High-acuity hospital setting | 29.5 |

| Years of experience (excluding MIR; n = 967) | |

| <5 years | 12.7 |

| 5−10 years | 16.1 |

| 10−15 years | 17.9 |

| 16−20 years | 13.0 |

| >20 years | 40.2 |

| Years in current position (excluding MIR; n = 959) | |

| <5 years | 34,1 |

| 5−10 years | 22,1 |

| 10−15 years | 14,2 |

| 16−20 years | 11,6 |

| >20 years | 18,0 |

For categories in which there are missing data, we present the number of participants included in the analysis (n). For the variables for which MIR trainees were excluded, we only show the n value if there were missing data.

Abbreviation: MIR, medical intern-resident trainee.

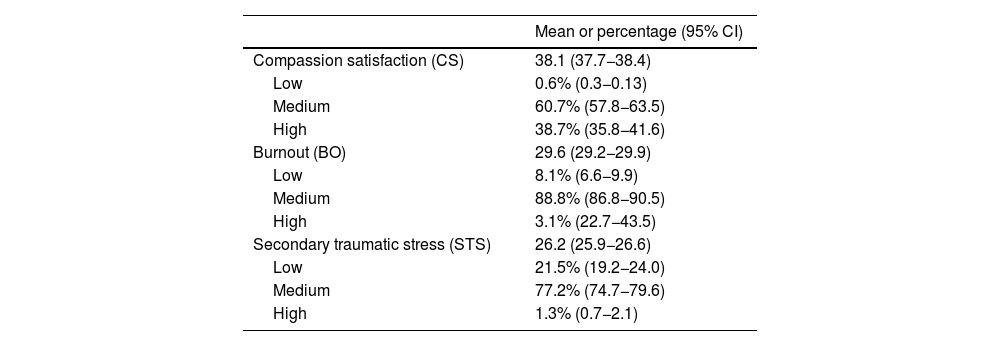

Table 3 presents the overall results of the ProQOL. Most participants scored in the medium range for the three subscales, with very small percentages in the groups with low CS or high BO or STS.

Results obtained in the total sample of pediatricians for the compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress subscales of the ProQOL scale for analysis of professional quality of life, expressed as a mean or percentage and 95% confidence interval.

| Mean or percentage (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Compassion satisfaction (CS) | 38.1 (37.7−38.4) |

| Low | 0.6% (0.3−0.13) |

| Medium | 60.7% (57.8−63.5) |

| High | 38.7% (35.8−41.6) |

| Burnout (BO) | 29.6 (29.2−29.9) |

| Low | 8.1% (6.6−9.9) |

| Medium | 88.8% (86.8−90.5) |

| High | 3.1% (22.7−43.5) |

| Secondary traumatic stress (STS) | 26.2 (25.9−26.6) |

| Low | 21.5% (19.2−24.0) |

| Medium | 77.2% (74.7−79.6) |

| High | 1.3% (0.7−2.1) |

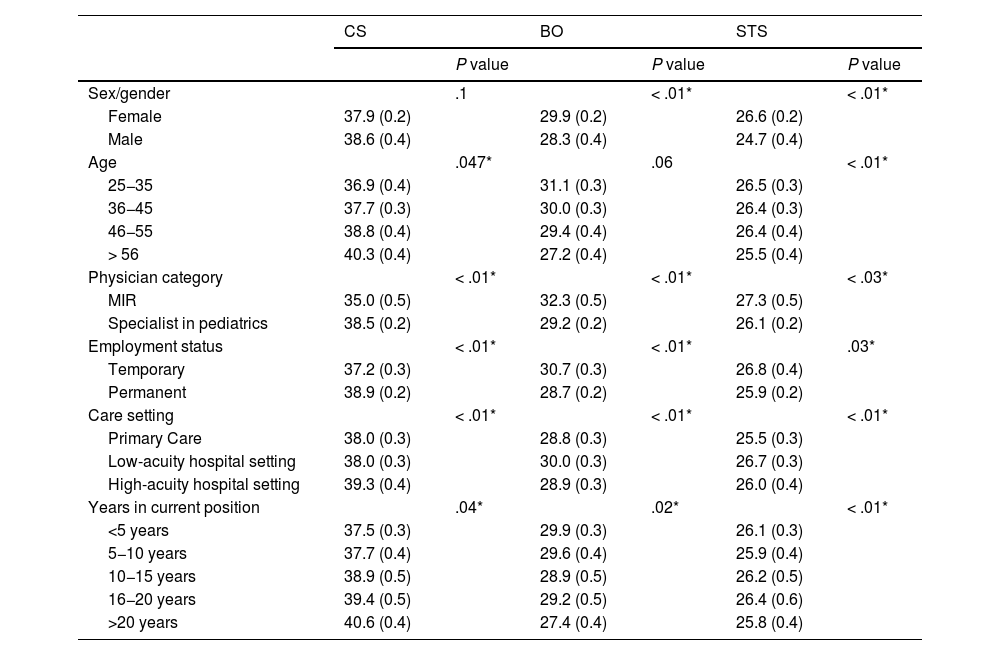

Table 4 summarizes the results of the exploratory comparative analysis. In the case of sex/gender, for mathematical reasons, we excluded the response corresponding to the “other” gender category, which scored in the medium range for every variable. We found significantly higher scores in the CF subscales (BO and STS) among female respondents. Increasing age was associated with a linear increase in CS and an exponential decrease in STS.

Comparison of the results obtained in the subscales of the ProQOL based on sex/gender, age, professional category (MIR vs specialist), subspeciality category/care setting, type of employment and time in current position (MIR trainees excluded from the last three).

| CS | BO | STS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | P value | P value | ||||

| Sex/gender | .1 | < .01* | < .01* | |||

| Female | 37.9 (0.2) | 29.9 (0.2) | 26.6 (0.2) | |||

| Male | 38.6 (0.4) | 28.3 (0.4) | 24.7 (0.4) | |||

| Age | .047* | .06 | < .01* | |||

| 25−35 | 36.9 (0.4) | 31.1 (0.3) | 26.5 (0.3) | |||

| 36−45 | 37.7 (0.3) | 30.0 (0.3) | 26.4 (0.3) | |||

| 46−55 | 38.8 (0.4) | 29.4 (0.4) | 26.4 (0.4) | |||

| > 56 | 40.3 (0.4) | 27.2 (0.4) | 25.5 (0.4) | |||

| Physician category | < .01* | < .01* | < .03* | |||

| MIR | 35.0 (0.5) | 32.3 (0.5) | 27.3 (0.5) | |||

| Specialist in pediatrics | 38.5 (0.2) | 29.2 (0.2) | 26.1 (0.2) | |||

| Employment status | < .01* | < .01* | .03* | |||

| Temporary | 37.2 (0.3) | 30.7 (0.3) | 26.8 (0.4) | |||

| Permanent | 38.9 (0.2) | 28.7 (0.2) | 25.9 (0.2) | |||

| Care setting | < .01* | < .01* | < .01* | |||

| Primary Care | 38.0 (0.3) | 28.8 (0.3) | 25.5 (0.3) | |||

| Low-acuity hospital setting | 38.0 (0.3) | 30.0 (0.3) | 26.7 (0.3) | |||

| High-acuity hospital setting | 39.3 (0.4) | 28.9 (0.3) | 26.0 (0.4) | |||

| Years in current position | .04* | .02* | < .01* | |||

| <5 years | 37.5 (0.3) | 29.9 (0.3) | 26.1 (0.3) | |||

| 5−10 years | 37.7 (0.4) | 29.6 (0.4) | 25.9 (0.4) | |||

| 10−15 years | 38.9 (0.5) | 28.9 (0.5) | 26.2 (0.5) | |||

| 16−20 years | 39.4 (0.5) | 29.2 (0.5) | 26.4 (0.6) | |||

| >20 years | 40.6 (0.4) | 27.4 (0.4) | 25.8 (0.4) | |||

Scores expressed as mean (SD) for each group. *Statistically significant.

Abbreviations: BO, burnout; CS, compassion satisfaction; MIR, medical intern-resident trainee; ProQOL, Professional Quality of Life scale; STS, secondary traumatic stress.

As regards work-related variables, MIR trainees scored lower in CS and higher in the two CF scales, while an increasing number of years in the current position was associated with a linear increase in CS and a linear decrease in BO, with significant differences in STS but without a discernible ordinal pattern. In the analysis by type of employment, we eventually chose to exclude respondents who were retired or self-employed due to the small size of the subset compared to those who held permanent and temporary positions. Permanent staff scored higher in CS and lower in BO and STS. We also found differences in the scores of the three subscales based on the pediatric subspeciality categories. Although the methods did not allow for differentiation among each of the different subspeciality categories, we found higher CS scores among respondents working in high-acuity hospital care settings and higher BO scores among those working in low-acuity hospital care settings, while the difference could not be evaluated for STS.

When we fitted linear regression models for each of the primary study variables, in the case of CS, the factors that were included in the final model were working in a high-acuity subspeciality (coefficient, 1.4), having held the current position for 20 or more years (coefficient, 1.2) and greater age, with the correlation coefficient increasing progressively with increasing age (coefficient, 1.0 for age 36−45 years, 2.0 for age 46−55 years and 3.0 for age >56 years). In the BO model, the associated variables were female sex (coefficient, 1.0), age, although there was only a significant difference between the oldest age group compared to all others (coefficient, −2.0), temporary employment (coefficient, 1.5) and working in a low-acuity hospital-based pediatric care setting (coefficient, 0,9). For the TS subscale, the factors identified as determinants in the model were female sex (coefficient, 2.1), working in a low-acuity hospital setting (coefficient, 1.0) and temporary employment (coefficient, 0.9).

DiscussionOur study, conducted through the self-administration by pediatric providers of the ProQOL questionnaire for assessment of professional quality of life, found significant levels of CF, measured in terms of both BO and STS, among the pediatricians working in Spain that submitted responses. Compassion fatigue was greater in providers who were younger, female or held temporary positions.

The findings of our study in Spanish pediatricians were similar to those reported in other populations, evincing the need to address the issue of CF in our country. We identified several factors potentially associated with a poorer pQoL, chief among them age, temporary employment and female sex. The scores in our sample for all three subscales were similar to those reported in a meta-analysis that included data from 11 countries24 and other studies published in countries such as Nepal,25 United States26 or Vietnam.27

The potential protective factors for pQoL identified in our study were greater age and longer work experience, which was consistent with a large volume of evidence showing that older and more experienced providers exhibit significantly greater CS and lesser BO,25,27–30 as MIR trainees scored lower in CS and higher in the two CF subscales and, as the number of years in the current position increased, there was a linear increase in CS and a linear decrease in BO, in addition to significant differences in STS. A possible interpretation is that older and more experienced providers, due to their greater exposure to the difficulties and challenges faced by patients, may become more adaptable and be better equipped to manage their own stress and exhaustion.27,31 In contrast, younger and more inexperienced workers may not be mentally prepared to face the extreme situations that patients experience on a daily basis.

One of the salient findings of our study was the association of provider sex with CF. A recent meta-analysis of studies conducted among physicians in Spain did not identify differences in relation to sex/gender, with the authors suggesting, nonetheless, that it is important to consider the gender perspective.32,33 Our study, conducted in a group with a large proportion of female providers (pediatric care), supports this view.

In respect of the pediatric subspecialities, we found higher CS scores in providers working in high-acuity hospital-based settings (neonatology, intensive care, palliative care, oncology and emergency care) and higher BO scores in low-acuity hospital-based settings (all other). The increased exposure of providers to complex situations in high-acuity specialties, involving considerable suffering in children and their families, may be associated with increased development of adequate protective strategies to prevent BO and STS in providers while promoting CS. Previous studies have found differences in relation to acuity, showing a lower prevalence of BO in surgery departments compared to other specialities,34,35 a higher prevalence of BO and STS in intensive care units,24,34 and a higher prevalence of CS and lower prevalence of BO in palliative care.36

However, we did not find scientific evidence on the association between the type of employment contract and pQoL, while one of the findings in our study was that providers with permanent positions scored higher on CS and lower on BO and STS. Job insecurity may be an organizational barrier hindering compassionate care.

There are several limitations to this study. First of all, we need to highlight the low response rate relative to the total number of AEP members (1112 responses out of a total of 13 584 members), although the number of submitted responses can be considered high for this type of study. There is also a risk of selection bias, as pediatricians who are more affected could be more likely to respond. Other factors, such as time constraints or the ease of completing the questionnaire online, could also lead to differential participation among the population of pediatricians. In addition, we did not study other variables that have been found to be associated with pQoL, such as income27,37 or marital status.30,34,38 In any case, we did not establish a working hypothesis and the performance of multiple comparisons could have led us to find spurious associations. Even the results of the logistic regression analysis should be interpreted with caution, given the sampling method. Future studies should randomly recruit pediatricians or even quota sampling to allow a more reliable analysis of the impact of various factors on the outcomes of interest. Among the strengths of the study, we ought to highlight its focus on pediatric care and the assessment of CF in pediatricians who practice in Spain by means of a questionnaire validated for use in the Spanish population. The pQoL of pediatricians is an aspect that needs to be studied in detail to protect and promote current and future health care quality.

In conclusion, our study found CF, STS and CS levels in a cohort of pediatricians in Spain that were similar to those reported in studies conducted in other countries, evincing a poorer pQoL among providers of younger age, female sex or with temporary positions. Future studies and interventions should consider specific factors and opportunities for improvement, specifically including coping strategies appropriate for the needs of pediatricians in training and a gender perspective.

Ethical considerationsThe study adhered to good clinical practice and ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects established by the World Medical Association in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments through the last version from 2024, as well as the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine.20,21 On distributing the questionnaire, participants were informed that the information collected in the survey would be solely and exclusively used for the stated purposes, safeguarding the anonymity of respondents who completed it on a voluntary basis, in addition to the confidentiality of the collected data in adherence to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights.22,23

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the Asociación Española de Pediatría for enabling the distribution of the questionnaire among its members, as well as the members themselves for the time they devoted to responding.