The conflicts that arise when minors or their legal representatives refuse to receive medical treatment considered necessary by the paediatrician pose a serious ethical dilemma and also have a considerable emotional impact. In order to adequately tackle this rejection of medical treatment, there is to identify and attempt to understand the arguments of the people involved, to consider the context in each individual case and be conversant with the procedure to follow in life-threatening scenarios, taking into account bioethical considerations and the legal framework.

Los conflictos que se plantean al negarse el menor de edad o sus representantes a recibir un tratamiento considerado necesario por el pediatra suponen un importante problema ético y conllevan fuerte impacto emocional. Para afrontar el rechazo al tratamiento es necesario explorar y comprender las razones que aducen los implicados, considerar los factores contextuales de cada caso y conocer la conducta a seguir teniendo en cuenta consideraciones bioéticas y el fundamento legal.

As doctors we should try to comply with the maxim “cure sometimes, relieve often and comfort always”. When we cannot cure, because a patient refuses a beneficial treatment, it produces an emotional impact, which is not only distressing but presents us with serious problems with regard to patients’ rights and their limits and to the competence of children and adolescents and of their representatives. There is often an underlying failure of communication or misunderstandings for cultural or other reasons.1

The problem becomes more acute when the refusal of treatment entails a risk of death and when, in addition, the decision is taken by patients’ legal representatives or by medical professionals.

Such situations arise both at hospital level and in primary care in relation to treatments or preventive measures, such as vaccinations.2

The reasons for refusing a treatment may be based on doubts about the success of the treatment and its risks, religious beliefs3 or lack of confidence in the doctor. Moreover, a growing tendency to question traditional medicine can be observed, combined with the upsurge of alternative forms of medicine,4 indicating that the cause is failure to satisfy the patient's desire for information. Anti-science feeling in certain sectors of society is not merely an expression of postmodernism, but also of the fact that within the context of these alternative forms of medicine the patient is treated as a person.5

All this is connected with problems of legal nature in relation to the possession and exercise of the rights of minors.

Cases such as those set out below raise ethical problems that can be analysed using the deliberative method proposed by Diego Gracia.6

Clinical scenarios- 1.

Refusal of growth hormone (GH) therapy. Iván was aged 4 years 6 months and was referred from primary care (PC) to endocrinology for a short stature examination (−2.6 SDs). The only salient point was that as a neonate he had been small for his gestational age. At the conclusion of the study, the parents were informed that GH therapy was indicated and they signed the informed consent (IC) form and the treatment request. Once the treatment was approved, the parents were instructed in administration of GH, but they were very late in attending the appointment and it was observed that the child had not grown as expected. The parents admitted that they had not applied the treatment because “taking hormones is bad for you”. They were informed again in detail of the benefits of the treatment, but despite this the parents held firm to their decision, as they did not see any problem in the fact that the child was short.

- 2.

Lucía was 4 years old when she was diagnosed with standard-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). The treatment protocol consisted of remission induction chemotherapy (CT), followed by a consolidation phase, a reinduction phase and maintenance for 2 years with low-dose oral CT.

Having been informed of the remission of the disease at the end of induction, the parents considered that their daughter was “cured” and refused to administer further treatment.

Remission induction is insufficient to cure ALL, and if the treatment is halted at such an early stage, the disease reappears in almost 100% of cases. After a relapse, the prognosis worsens, since the delay in treatment promotes the emergence of resistances. The haematologist, being aware of this serious risk, did not know how to deal with the case.

- 3.

Rebeca was 13 years old when she attended PC with her grandmother because she was very aggressive and “they couldn’t cope with her”. She was eating very little and was believed to be starting to suffer from an eating disorder (ED). The family had the impression that they were wasting their time and suspected purging behaviours. Rebeca said that “she had no problems, except that her parents were pestering her all day to eat” and that “she argued with her mother all the time”. Mild malnutrition was observed and an urgent appointment was requested with the child psychiatric service. The problem was that Rebeca refused to see any medical professional.

Ethical problems are always conflicts of values and they confront us with the question: “what should I do?” To analyse these conflicts we need to identify the values that come into play and distinguish them from prejudices and beliefs.

The subject is undeniably complex, but the following problems can be highlighted:

- 1.

Does a minor have the right to refuse a beneficial treatment that is not life-threatening? What if it does put their life at risk?

- 2.

At what age should the minor's opinion be taken into consideration?

- 3.

How should the minor's capacity to consent to or refuse a treatment be evaluated? Who should decide this?

- 4.

If it is agreed that a minor is capable of giving consent or refusal, should their decision be respected? Can they be persuaded, forced or lied to?

- 5.

Is consent by proxy absolute or does it have limits?

- 6.

Is it necessary to evaluate the capacity of representatives who refuse a vital treatment?

- 7.

Who is responsible for making the decisions on which the lives of minors depend?

- 8.

How should the concept of grave risk be defined?

Refusal of treatment brings into play 2 values that are important in themselves: respect for autonomy, on the one hand, and respect for the value of life and health, on the other, but neither of them has an absolute value that requires that it must prevail in all circumstances.7,8

The principle of autonomy allows a person to accept or refuse a given treatment and is given concrete form in IC, which constitutes the guarantee of the right to refuse medical treatment as an expression of bodily integrity.9

In order to be considered fully autonomous, a person must be free from duress and competent. Assessing the competence of a minor is a very complex matter and requires evaluating the degree of maturity, the gravity of the decision and the reparability or irreparability of the consequences of the decision,10 taking account of the circumstances and the context in which the decision is made.

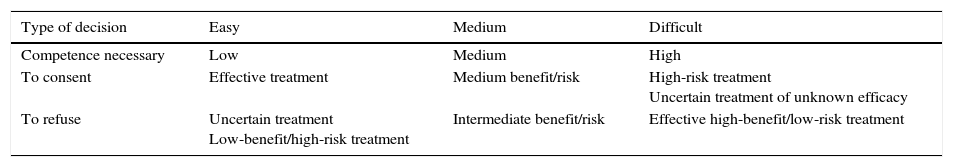

The gravity of the decision is assessed according to the risk/benefit and the proportionality of the decision: the graver the decision, the greater the level of competence that must be required of the person.11 For this purpose we use the sliding scale proposed by Drane, who considers that greater maturity should be required of minors who oppose a doctor's opinion than of those who comply with it12 (Table 1).

Drane's sliding scale of competence.

| Type of decision | Easy | Medium | Difficult |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competence necessary | Low | Medium | High |

| To consent | Effective treatment | Medium benefit/risk | High-risk treatment Uncertain treatment of unknown efficacy |

| To refuse | Uncertain treatment Low-benefit/high-risk treatment | Intermediate benefit/risk | Effective high-benefit/low-risk treatment |

In non-competent minors, IC is by proxy; in other words, it is the responsibility of parents or guardians, and its governing principle is the best interest of the minor. But minors must be allowed to exercise their fundamental rights as soon as they have capacity to do so and their opinions, preferences and values must be respected to the extent that they are not contrary to their best interests; that is, they must be protected when their life is put in danger. When the best interests of the parents and the medical professionals do not coincide, and especially in life-threatening or exceptional circumstances, the suitability of the representatives can be considered questionable, particularly if they contradict the known wishes of the minor or do not represent the best interest of the minor but that of the family or of a particular group. These circumstances constitute an exception to IC by proxy and medical professionals can apply to a judge to replace such representatives, after consulting the Healthcare Ethics Committee (HEC) to ascertain whether this is possible.

Legal basisProvision is made for minors as a legal entity in Act 41/2002, of 14 November, the Basic Act Regulating Patient Autonomy (LBAP in Spanish), which covered a gap in the law on this issue; in this regard, the age of majority for healthcare purposes was set at 16 years, with certain exceptions. Up until then only the 1996 Child Protection Act had supported promoting the autonomy of minors, whenever possible.13,14 Another important landmark was Judgment 154/2002 of the Constitutional Court on a 13-year-old boy who had refused to receive a blood transfusion in a situation of grave risk. It bore expressly on the degree of irreversibility of decisions made, as did Circular 1/2012 of the Public Prosecutors’ Office in a document on conflicts over blood transfusions in minors in cases of grave risk.15

It is important to highlight 3 fundamental premises:

- –

The healthcare model is governed by a basic principle: the patient has the right to decide freely and voluntarily, by means of IC, between the clinical options available, and these options include refusing treatment.

- –

In the legal system life is a supreme value, and is therefore positively protected. The right of minors to life and health, in cases where taking action causes an irreparable loss, cannot be subordinated to the right of minors or their parents to freedom of conscience.

- –

The public authorities must ensure the social, economic and legal protection of families, and particularly of minors.16

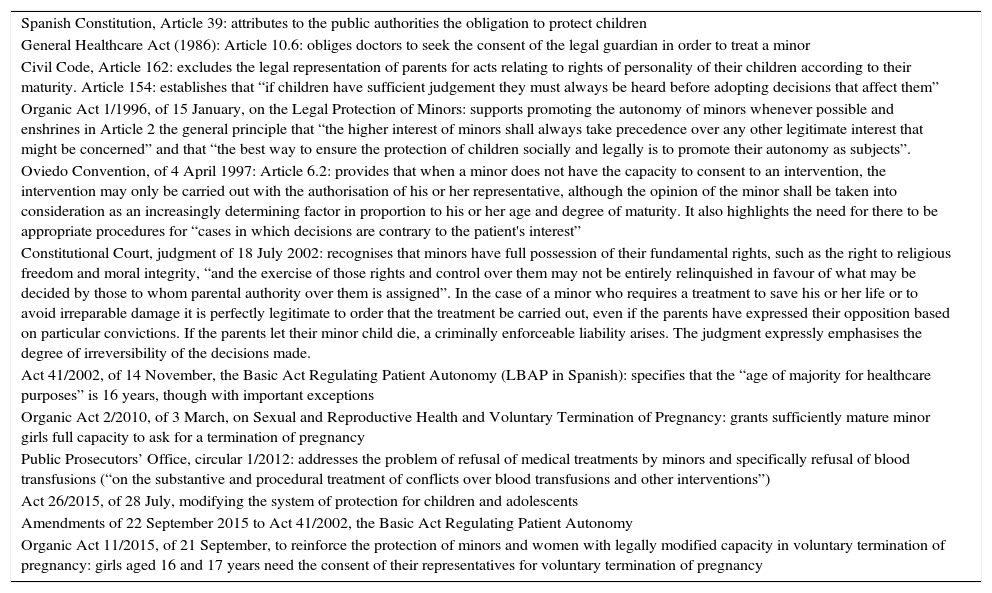

The laws affecting minors in the areas of protection in general and protection of health in particular are summarised in Table 2.

Laws affecting minors in the area of health and protection.

| Spanish Constitution, Article 39: attributes to the public authorities the obligation to protect children |

| General Healthcare Act (1986): Article 10.6: obliges doctors to seek the consent of the legal guardian in order to treat a minor |

| Civil Code, Article 162: excludes the legal representation of parents for acts relating to rights of personality of their children according to their maturity. Article 154: establishes that “if children have sufficient judgement they must always be heard before adopting decisions that affect them” |

| Organic Act 1/1996, of 15 January, on the Legal Protection of Minors: supports promoting the autonomy of minors whenever possible and enshrines in Article 2 the general principle that “the higher interest of minors shall always take precedence over any other legitimate interest that might be concerned” and that “the best way to ensure the protection of children socially and legally is to promote their autonomy as subjects”. |

| Oviedo Convention, of 4 April 1997: Article 6.2: provides that when a minor does not have the capacity to consent to an intervention, the intervention may only be carried out with the authorisation of his or her representative, although the opinion of the minor shall be taken into consideration as an increasingly determining factor in proportion to his or her age and degree of maturity. It also highlights the need for there to be appropriate procedures for “cases in which decisions are contrary to the patient's interest” |

| Constitutional Court, judgment of 18 July 2002: recognises that minors have full possession of their fundamental rights, such as the right to religious freedom and moral integrity, “and the exercise of those rights and control over them may not be entirely relinquished in favour of what may be decided by those to whom parental authority over them is assigned”. In the case of a minor who requires a treatment to save his or her life or to avoid irreparable damage it is perfectly legitimate to order that the treatment be carried out, even if the parents have expressed their opposition based on particular convictions. If the parents let their minor child die, a criminally enforceable liability arises. The judgment expressly emphasises the degree of irreversibility of the decisions made. |

| Act 41/2002, of 14 November, the Basic Act Regulating Patient Autonomy (LBAP in Spanish): specifies that the “age of majority for healthcare purposes” is 16 years, though with important exceptions |

| Organic Act 2/2010, of 3 March, on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy: grants sufficiently mature minor girls full capacity to ask for a termination of pregnancy |

| Public Prosecutors’ Office, circular 1/2012: addresses the problem of refusal of medical treatments by minors and specifically refusal of blood transfusions (“on the substantive and procedural treatment of conflicts over blood transfusions and other interventions”) |

| Act 26/2015, of 28 July, modifying the system of protection for children and adolescents |

| Amendments of 22 September 2015 to Act 41/2002, the Basic Act Regulating Patient Autonomy |

| Organic Act 11/2015, of 21 September, to reinforce the protection of minors and women with legally modified capacity in voluntary termination of pregnancy: girls aged 16 and 17 years need the consent of their representatives for voluntary termination of pregnancy |

The legal position of minors introduced by Act 41/2002 has recently been updated through Act 26/2015, of 28 July, modifying the system of protection for children and adolescents,17,18 because of doubts about the real scope of the new age of majority of 16 years for healthcare purposes (objective criterion) and the practical effectiveness of the exception for grave risk. This Act makes it clear that the capacity of minors aged 16 years or more does not apply in cases in which there is a grave risk to their life or health, and that the decision in such cases is to be taken by the minor's legal representatives, not the doctor, as the original wording of Act 41/2002 could be understood to mean, provided that the former act in the best interest of the minor.

However, one of the main problems posed by the new regulation is whether minors aged 16 years can be considered to have the capacity to decide according to their real moral maturity (subjective criterion). An interpretation of the new Act as a whole would make it possible to argue that the reform adopts a mixed criterion, objective in respect of a reference age, 16 years, and subjective for those cases in which a 16-year-old minor is seen as being intellectual and emotionally capable of understanding the intervention, albeit with the exception of those cases in which there is a grave risk to the life or health of the minor, in which case the age of capacity for making the decision is raised to 18 years.

In addition, the new Act also clarifies the power of legal representatives with regard to refusal of treatment, which can only be exercised to the benefit of the minor.

To sum up, following the 2015 reform of Act 41/2002 we can highlight 3 important ideas:

- 1.

The objective criterion of age (16 years) is now supplemented by a subjective criterion (real maturity), which allows the decisions of 16-year-old minors to be complied with, taking into account the real maturity of the minor, the context in which the decision is made and its risks.

- 2.

The age of majority of 16 years for healthcare purposes does not apply when there is a grave risk to the life or health of the minor.

- 3.

The minor's representatives must act in his or her best interest, and the doctor can adopt a decision in favour of that best interest when the decision the parents wish to adopt is contrary to it. When there is no urgency to make the decision, the help of judicial authority must be obtained directly or through the Public Prosecutors’ Office. If the decision is urgent, due safeguarding of the patient's life or health, under the justification of necessity, can be considered the “best interest”, even against the will of the parents.

Case 1. The refusal of GH replacement therapy did not represent a life-threatening risk for Iván, and his parents were not concerned about him being shorter than was to be expected; their decision was therefore respected. It may be that as the child grows up he will find he is affected by his height, in which case a new assessment could be made, or he may challenge his parents on the decision they took at the time. Accepting short stature is a personal option that conflicts with the current culture of aesthetic improvement.

Case 2. Lucía had a serious illness and the absence of full treatment involved a severe risk of life-threatening relapse. Her parents’ decision not to treat on the basis of their beliefs cannot be taken into account, since the right to health in minors takes precedence over their parents’ freedom of conscience. For this reason, and after numerous conversations with the parents, who were incapable of accepting other arguments, it was decided to take the matter to a judge, who temporarily withdrew guardianship of the girl in order to continue treatment according to protocol. The process was conducted satisfactorily and the girl is currently in ongoing full remission.

Case 3. Rebeca was not aware of her disorder, as is usually the case in EDs, in which the capacity of adolescents to make fully autonomous decisions is impaired. It was an incipient case, but if it was allowed to develop it could have become serious. In this situation, it is ethically acceptable to intervene therapeutically, even against the wishes of the minor, not without asking oneself whether the intervention is paternalism or good clinical practice.19,20 Rebeca's parents finally managed to get her to see a child psychiatrist and control her process.

Recommendations for situations of conflictIn situations of conflict it may be useful to implement a series of tiered measures:

- –

Take account of the reasons that have led the minor to decide to refuse treatment.

- –

Ensure good communication with the parents and, if possible, with the child. There must be two-way communication that manages to get each party to understand the other's options and arguments. Sometimes the help of cultural or spiritual mediators is needed.

- –

Consider the possibility of extending the information to other family members.

- –

Consult the HEC. If the situation persists, the final step is to apply for judicial authorisation and wait for the reply, if it is not a life-threatening emergency. If the latter is the case, it is legitimate to act, under the justification of necessity, although notification must be made as soon as possible.

- –

Patients must never be abandoned. They must be guaranteed care and offered a safe environment.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Jacob M, Tasso Cereceda M, Martínez González C, de Montalvo Jááskeläinem F, Riaño Galán I, Comité de Bioética de la AEP. Reflexiones del Comité de Bioética de la AEP sobre el rechazo de tratamientos vitales y no vitales en el menor. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87:175–175.